A crowd protesting against Pravin Gordhan’s address at a fundraiser for the Concerned Citizen’s Group in KwaDukuza clashed violently with the audience.

NEWS ANALYSIS

‘This town is run by a mafia,” someone says between teeth gritted against the stench of human faeces that permeates the entrance to the Stanger Siva Sungum hall.

It is a humid Sunday on the KwaZulu-Natal North Coast and KwaDukuza is expecting former finance minister Pravin Gordhan to address a fund-raising dinner for the Concerned Citizens Group (CCG).

The two buckets of shit splattered across the hall’s entrance are Gordhan’s welcoming garland.

“Two people walked up to the front and said: ‘We have come to deliver this.’ They shook their buckets and then threw it all over the entrance,” says Wendy Nyanda, one of several people mopping up the watery excrement.

The “mafia” responsible are apparently motivated by ANC factional politics — the region is a staunch supporter of President Jacob Zuma and Gordhan’s presence is considered an affront to Zuma’s ANC.

The ANC’s Greater KwaDukuza region is holding its general congress nearby and rumours circulate that the provincial and regional leaders, who support Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, could not countenance Gordhan’s presence, hence the disruption — flatly denied by these structures, and the provincial ANC Youth League, on Monday.

Another apparent reason for the turd-throwing is the CCG’s high court case against the KwaDukuza municipality and Zuma-linked businessman Vivian Reddy.

The civic organisation is challenging the R9-million sale of the municipal sports grounds to Reddy, who is building a mall on the land. They say an evaluation closer to R60-million was more appropriate. The groundworks have already begun on what used to be the town’s cricket oval, football pitches, swimming pool, tennis and basketball courts and a nine-hole golf course.

A group of bussed-in protesters are gathering up the road from the hall. A few are wearing T-shirts supporting Dlamini-Zuma. Others are dressed in ANC Youth League T-shirts, but most wear the everyday clothes of the unemployed: garments frayed and faded by use and time.

Sheets of white A4 paper are handed out to the protesters. They are aimed at Gordhan and read: “You are dividing the ANC”, “PG The darling of the ‘DA’” and “PG is the co-author of ‘President’s Keepers’”. The last is a reference to Jacques Pauw’s book The President’s Keepers: Those Keeping Zuma in Power and out of Prison.

Dressed in an ANC T-shirt with Zuma’s face on the front, Lucky Mbokazi says Gordhan “has no business coming here to intervene”.

“According to the ANC rules he should not be in KwaDukuza municipality. Why didn’t [the CCG] call [current Finance Minister] Malusi Gigaba to address them?” he asks.

“Is this about Dlamini-Zuma versus Cyril Ramaphosa?” I ask.

“You got it, my man, you got it.”

The group expands to about 50 people; none appear to be older than 35. This is mainly a rent-a-crowd and some appear to have been recruited from the shebeen. Some people tell the Mail & Guardian that they are there because they were “told” that the CCG wants to stop the mall development and deprive them of jobs.

CCG chairperson Haroon Mohammedy denies this. He says the group is questioning why the municipality would destroy the town’s sporting facilities and sell off its assets so cheaply.

Sbonelo Zubane is 23, and from the local Shakaville township. He is unemployed and angry. He is also a little tipsy, but unapologetic about this. “I have nothing. I can’t get a job and there is nothing for me to do here,” he says. “I am owed something, because my grandfather was killed in Namibia while serving in Umkhonto weSizwe.”

Zubane’s friends, Bongani Mhlongo and Sanele Mthiyane, agree that jobs are scarce and when they are lucky enough to get a “piece job”, the pay is low. “We were told to come here because people want to close the mall down,” Mthiyane says.

According to the 2011 census KwaDukuza has just over 70 000 urban households and 66.7% of the population are between the ages of 15 and 64. Unemployment is at 25% and youth unemployment is 30.8%.

The minutes of a special municipal council meeting in 2015 reveal the mall is projected to create 500 jobs.

Mthiyane says jobs have been scarce during the mall’s construction phase: “The companies bring their own workers from outside and are only employing two people from every ward — but you have to be a ward committee member to get one of those jobs,” he says.

A few days later I speak to Zubane again. He says he used to play football on the old Country Club grounds. Where there was once grass, there are now grey concrete pillars stuck into the red clay. He bemoans the fact that the “kids in my area have nowhere to play sport”.

Why, then, was he at the protest?

“I was at the hall because those people didn’t consult with the community before having their meeting,” he says. “I am actually opposed to the mall being built there, because it has taken away my community’s sports grounds — we all used it — but they must come and speak to our communities before taking decisions.”

On Sunday, Gordhan starts to address those in the hall — business people, activists, sports administrators, teachers and leaders from the South African Communist Party (SACP) and labour federation Cosatu.

Formerly known as Stanger, KwaDukuza has a deep political history. People remember ANC president Albert Luthuli stopping his chats with activists and friends who owned shops in the town centre to shake the hands of children walking to school. He would urge them to apply themselves so that they would be ready “when freedom came”.

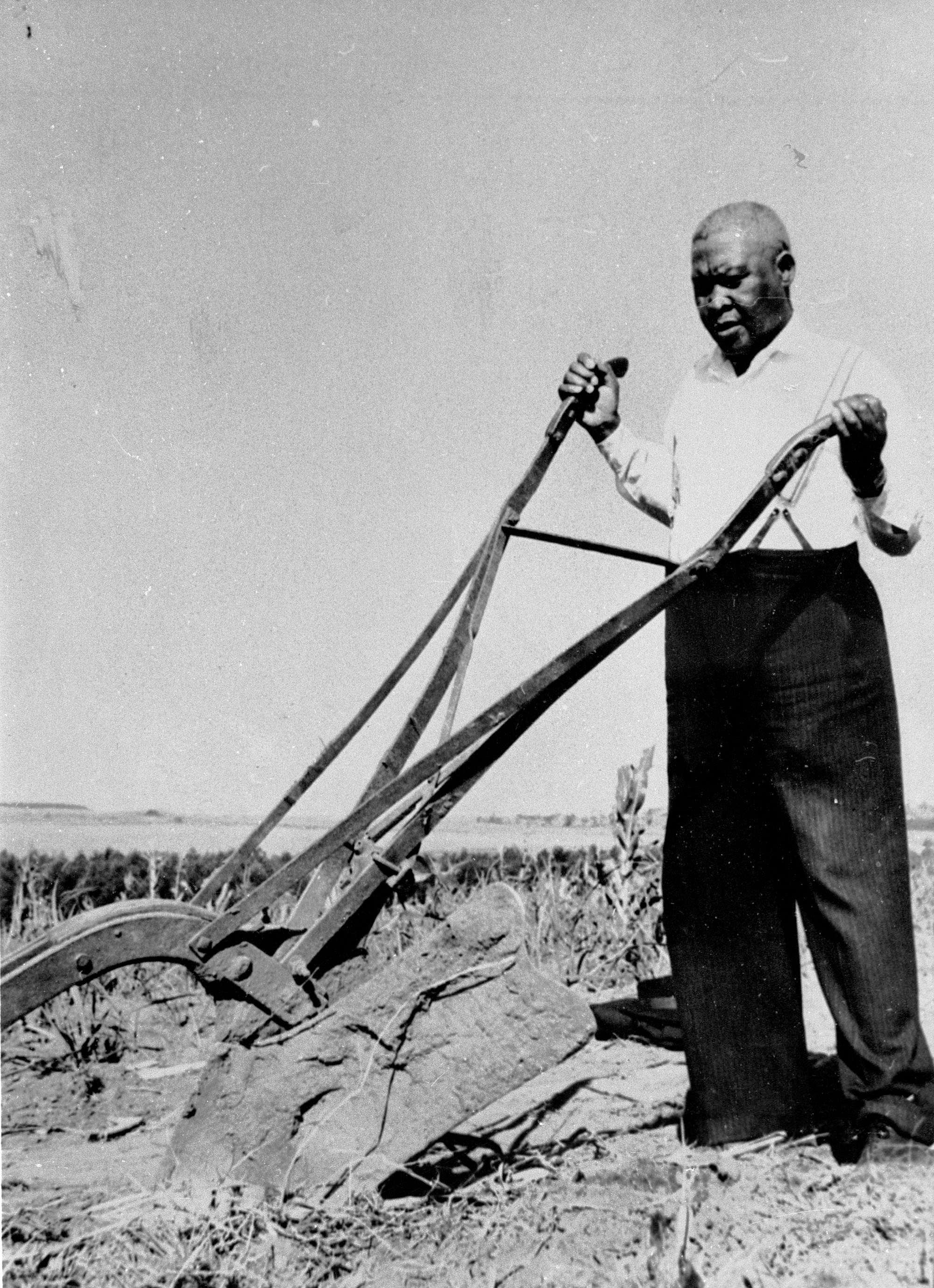

[Former ANC president Albert Luthuli is fondly remembered by some KwaDukuza residents. (UWC Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)]

Perhaps Kader Asmal was one of those local children. He met Luthuli while still at school and was inspired to become politically active. The late chief justice Pius Langa studied in KwaDukuza until grade eight, before moving to Adams College. He later returned to the town as a prosecutor.

After the unbanning of the ANC, the movement’s very first branch in the country was set up in KwaDukuza. Some of the people who established that branch are sitting in the hall, including its first chairperson, the lawyer Riaz Meer.

Gordhan starts sketching out his talk. It is about state capture, about wealth redistribution and about holding government to account during a fragile time for South Africa’s democracy. He doesn’t get very far.

Outside the crowd is getting louder. They storm in, throwing food and drinks on the floor. A woman shrieks: “Oh my God, they are going to touch the food!”

People manage to push the invaders out and barricade the doors. People outside accuse those inside of being racists, of stymying development and of “not belonging in this country”. Surreally, some shout that those inside must “Go back to Dubai!” and “Go back to India!”

The skirmishes get increasingly violent. The police do little.

The interruptions prevent Gordhan from completing his speech and he leaves to catch his flight. Soon after, the crowd leave. The mood is subdued and the CCG decide not to auction two paintings — of Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela.

Meer remembers Mandela’s visit to the town after his release from Robben Island in 1990. He had spent the night before his 1962 arrest at the house of Goolam Suleman in the Indians-only area of Tinley Manor, near the beach reserved for KwaDukuza’s black population. During his 1990 visit he again stayed with Suleman and Meer remembers them re-enacting the 1962 Howick trip — including the 1am knock on the door to rouse Mandela — the next day. “Madiba was thrilled,” Meer says.

“Then ANC treasurer general Thomas Nkobi and secretary general Alfred Nzo were with Madiba and they stayed at my mother’s house that night. You wouldn’t find that happening today. Leaders want seven-star hotels, not just the five-star ones,” Meer says, laughing.

Edwin Pillay, former South African Democratic Teachers Union deputy president and Cosatu central executive committee member, was at the fundraiser: “What happened at the dinner was an indication of how factional the ANC has become. It is frightening that this level of intolerance has grown in the party, because it goes against our founding values,” he says. Pillay was also involved in the creation of the Stanger ANC branch and the teachers union.

Another former ANC leader was blunt: “Any viewpoint outside of what Zuma is all about is harshly criticised by ANC structures in this town, which is overwhelmingly behind the president and his preferred candidate.”

SACP district secretary Mbuso Khuzwayo says: “[Former Zimbabwean president Robert] Mugabe used the unemployed youth to intimidate the opposition and that is exactly what happened here today.”

Outside the hall a member of the original ANC Stanger branch tells me there have been door-to-door signature campaigns in his ward and he had unwittingly signed the register for an ANC branch general meeting. The branch got enough signatures to “quorate” and will send a delegate to the ANC’s elective conference to back Dlamini-Zuma.

Khuzwayo says he attended the fundraiser rather than the regional congress because: “I don’t want to be an alibi to what is happening there. They are killing the ANC.” He adds he was ejected from his branch general meeting despite being a paid-up ANC member.

Another member of the original Stanger ANC branch said of his current ward-based branch: “In the recent national and local government elections the only people campaigning for the ANC have been politicians, municipal officials, candidates, the candidates’ families and tenderpreneurs — everyone who had a serious monetary vested interest. No activists, not any longer.”

Niren Tolsi is a former resident of KwaDukuza. A relative and a former teacher of his are members of the Concerned Citizens Group