Elusive: The documentary Chasing Trane fails to catch the full John Coltrane.

In Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary, directed and written by John Scheinfeld, there are parts where you begin to feel like the title is purposefully metaphorical. We are on a quest for a window into Coltrane’s spirit, the essence of what makes him luminous. However, we are always one step behind. It is a strange sensation, the feeling that all we are getting to know about the man is ephemeral or perhaps even irrelevant.

But that could be the beauty of the documentary: the pursuit of a seemingly impossible task, the triumphs of the experience more attributable to the subject than to the filmmaking.

In many respects, Chasing Trane (available on Netflix) is an ordinary film. It is unassuming, much like the subject himself. It maintains something of an even keel, allowing Coltrane’s extraordinary life journey to work its own emotions on you.

In the late Fifties, he quits (cold turkey) a crippling heroin addiction at what was then the height of his career as a jazz saxophonist — a move that opens him up spiritually, eventually clearing the path for the creation of A Love Supreme, recorded in 1964. You may shed a tear in cognisance of your own breakthroughs in life.

When Coltrane loses a number of family members in quick succession as a preteen boy, you may be stunned by the unrelenting brutality of it all but you will also marvel at how a young man gradually learns to channel his pain, spurred on by his mother.

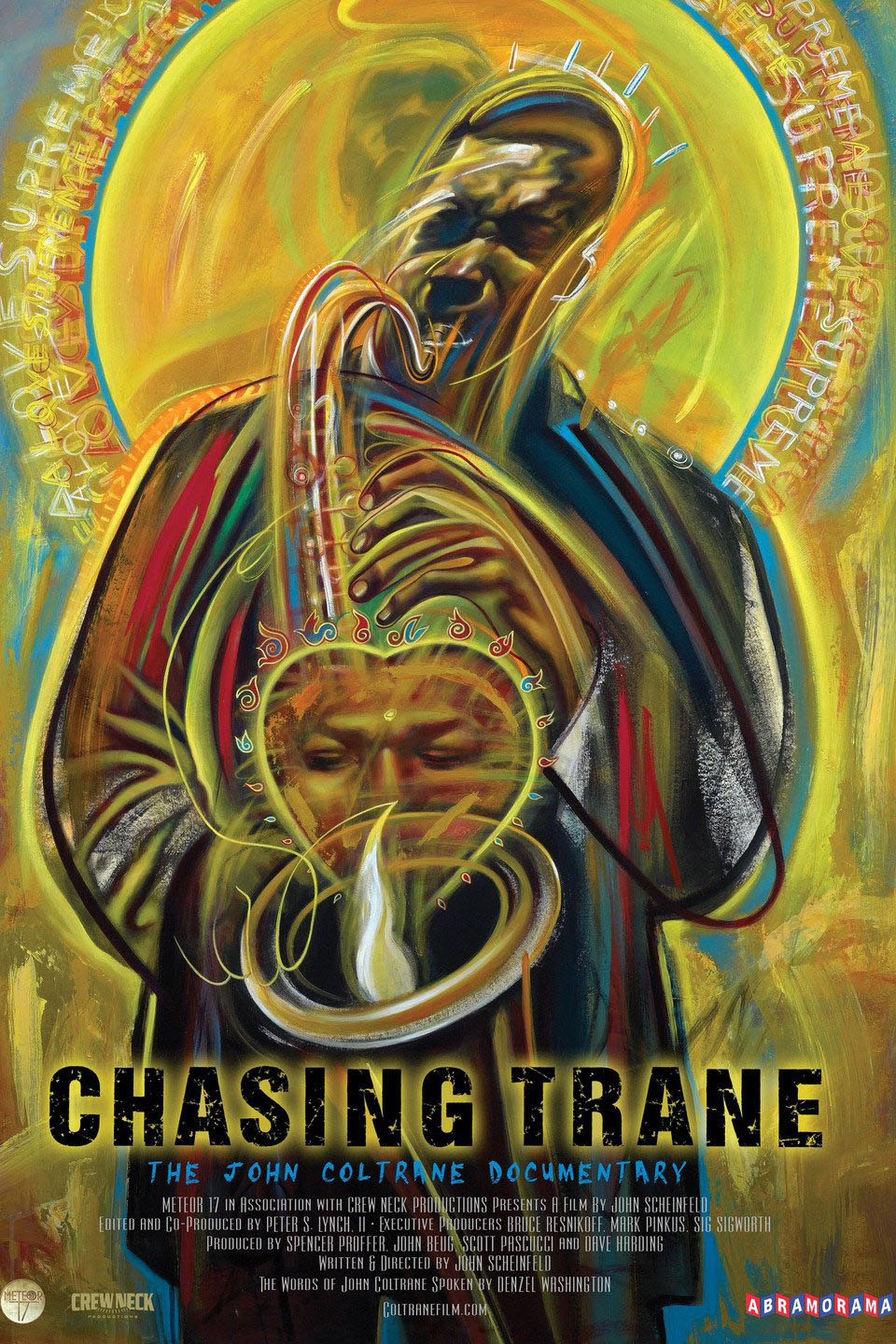

Gradually, through anecdotes, the image we are fed of Coltrane is that of an almost silent man, a view reinforced by the sparing use of his own words, read unobtrusively by actor Denzel Washington. At times, the film feels like the deliberate sanctification of an already sanctified man.

Coltrane’s musical trajectory, from early naval band recordings in which he apes Charlie Parker’s style to subsequent stints with Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis — both gigs cut short by his addiction — are familiar to even the most casual of Coltrane listeners.

How he picks himself up, informally playing with Thelonious Monk and rejoining Davis briefly as he kick-starts his own career as a bandleader, is the stuff of standard Wikipedia entries, rendered with sparing amounts of colour in the film.

How he eventually dismantles his quartet before building another ensemble and heading straight for the unseen is the stuff known even by neophyte listeners like myself, rendered with little idiosyncratic detail.

This is why many have argued that, indeed, the film may be pitched at passing traffic rather than at the aficionado. In and of itself, this is not an issue.

This is not to say there are no deeper hues to Scheinfeld’s retelling of this parable of a life. The talking heads, although numerous and frequent, all reinforce different aspects of the man. Some, though, are superfluous. Visually, the film looks stunning and does well to juggle lopsided material — specifically, an overabundance of photographs, a fair amount of home videos and not much concert footage.

Too little performance footage, perhaps? Small matter. Live renditions of Coltrane classics such as Alabama and Impressions are easy to find on YouTube. Very little of the concert footage we see here is new. What’s missing, perhaps, is more of Coltrane as an earthly figure. There is too much fawning over him as celestial.

For instance, how untenable was he as a band leader? I once stumbled on a film about the recording of the gruelling Ascension sessions. With their extended complement of personnel and heading into a free-jazz dimension, the tiresome, 40-odd minutes-a-piece live sessions got the better of drummer Elvin Jones, who tossed his drum kit against the studio walls, signalling the end of that recording.

How much of a toll did life on the road have on Naima, Coltrane’s first wife, and their relationship? Was it indeed hepatitis C as a result of heroin use that took his life at 40? How did the brisk entry of second wife Alice after his departure from home shape his family dynamics?

By this, I’m not advocating for a salacious picture but an understanding that our saints, be it Brenda, Winnie, Nina or Bob, are not deified because they led troubled, albeit singular lives, but because their blemishes helped us to understand, in a fundamental way, what it means to be human. To carry on despite your mistakes. To betray. To live. To sacrifice. To walk away from hurt, or those you love. To seek redemption at all costs. To be naive. To fail. To live. To retreat.

How many uncritical documentaries of Bob Marley can one stomach? How long can access continue to dictate the honesty of historiography? How long can we chase Trane when what he communicates is, in most cases, so easily translatable?

When all is said and done, Chasing Trane feels like an exhilarating ride through confirmation bias. It’s like the part where Wynton Marsalis says: “He went from playing that [referring to the navy era] to what he became. Man, that’s all you need to know about him.”