In Polokwane in 2007

COMMENT

In closing the ANC’s Polokwane conference in 2007, at which he became the party’s 12th president, Jacob Zuma’s message to delegates was simple but inspiring.

Zuma, the candidate of the left and the “coalition of the wounded”, as the “victims” of former president Thabo Mbeki were known, told delegates that the time to heal — and build — the ANC had arrived.

He emphasised that the conference resolutions “will guide us on our way forward” and that the economic policies adopted “do not indicate a fundamental shift from the policies that the ANC has adopted since it has come into power”.

“Let me reiterate that decisions with regard to policies in the ANC are taken by conference and not by an individual,” Zuma said. “As a collective and through our structures, we need to create a united ANC that recognises the legacy left by comrades OR Tambo, Albert Luthuli and Nelson Mandela.”

Outwardly magnanimous towards the vanquished Mbeki, Zuma said: “We need to heal the ANC.”

He added: “We must also work with government and other sectors to build a caring society. Most importantly, we need to position our branches and structures at the centre of the NDR [national democratic revolution], because the ANC is a people-centred and people-driven organisation.”

A decade later, his words ring as hollow as a dried butternut gourd.

Zuma’s leadership of the continent’s oldest liberation movement has, according to some members of his national executive committee and Cabinet who spoke to the Mail & Guardian, plunged the organisation into the abyss of crisis.

This view is echoed in secretary general Gwede Mantashe’s diagnostic report delivered to the ANC’s policy conference in June.

In Polokwane, the ANC pledged to fulfil the 1942 Bloemfontein conference resolution to target a million members by its centenary in 2012. It did this, but failed to ensure this membership drive was “accompanied by intensive branch political education programmes to improve the quality of members”.

Establishing a political school was to be “one of the key organisational priorities of the next five years”. The school is yet to be established.

Mantashe’s 2017 diagnostic report was critical of “weak induction programmes” that have led to “a big membership that does not understand the organisation”. ANC members, according to Mantashe, do not read policy documents, are bereft of “political and ideological clarity” and are driven by career aspirations and self-interest rather than activism — which is “in decline”.

This has entrenched factionalism and translated into “brutality against one another” as members vie for government positions and contracts while purging those who have not supported them.

This is most apparent in Zuma’s home province, KwaZulu-Natal, which drove the “Zunami” on which he surfed — and sang — his way to the ANC presidency.

KwaZulu-Natal has been racked by political assassinations in the aftermath of the “unlawful” 2015 provincial elective conference. The period saw the factional purging of the losers from both ANC leadership positions and government by the new pro-Zuma executive committee.

The new KwaZulu-Natal chairperson, Sihle Zikalala, much like Zuma in 2007, had preached reconciliation but purged the province to ensure it backed Zuma’s chosen successor for 2017 — Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma.

Even prior to 2015, there was a wave of killings in the province’s rural towns ahead of the 2011 local government elections and the 2012 ANC elective conference. So-called comrades meted out the “brutality” that Mantashe outlined in his diagnostic report as “a phenomenon of being with us or against us”.

The road to the 2016 local government elections and this weekend’s conference has been even more bloody. Premier Willies Mchunu was forced to appoint the Moerane commission into political killings last year. Ironically, murders have escalated in the province since the commission started sitting.

In 2007 the ANC had resolved to “strengthen list guidelines and processes” — to ensure “the best cadres” were deployed to public office and to involve the broader community in candidate selection.

Under Zuma’s presidency, power consolidation in the ANC means these words are abstracted niceties: councillors, mayors, premiers and Cabinet ministers are mainly deployed because of the factional support they have lent to those higher up in the ANC structures. Or to the president himself — with a little decision-making help from his Gupta friends.

The Imvuselelo campaign would ensure that branches “intensify” activist work in communities, establishing themselves as “vanguards” for social transformation, said the ANC at the Polokwane conference.

Instead, branches are moribund, according to Mantashe and ANC members on the ground. They only function for the party’s internal elections, which have become increasingly anti-democratic.

On the campaign trail in Limpopo in October, ANC presidential candidate Cyril Ramaphosa talked of branches where members were “stored in the deep freezer” and only defrosted when it was time to vote for new leadership. ANC members told the M&G of “door-to-door signature campaigns” to make the fraudulent claim that branches had quorated, discussed policy and potential leaders, and then come to decisions.

There is evidence, in court documents, of private security and municipal police keeping members out of branch general meetings because of the views they hold.

The Zuma decade has seen the rise of “lawfare” in the ANC. Disputed conference results have been taken to the high court in KwaZulu-Natal, the Eastern Cape, the Free State and the North West, and regions have fought their own court battles over disputed processes.

Despite Luthuli House saying issues must be resolved internally, the leadership’s inability to intervene without favour and ensure fair processes has turned members into litigants.

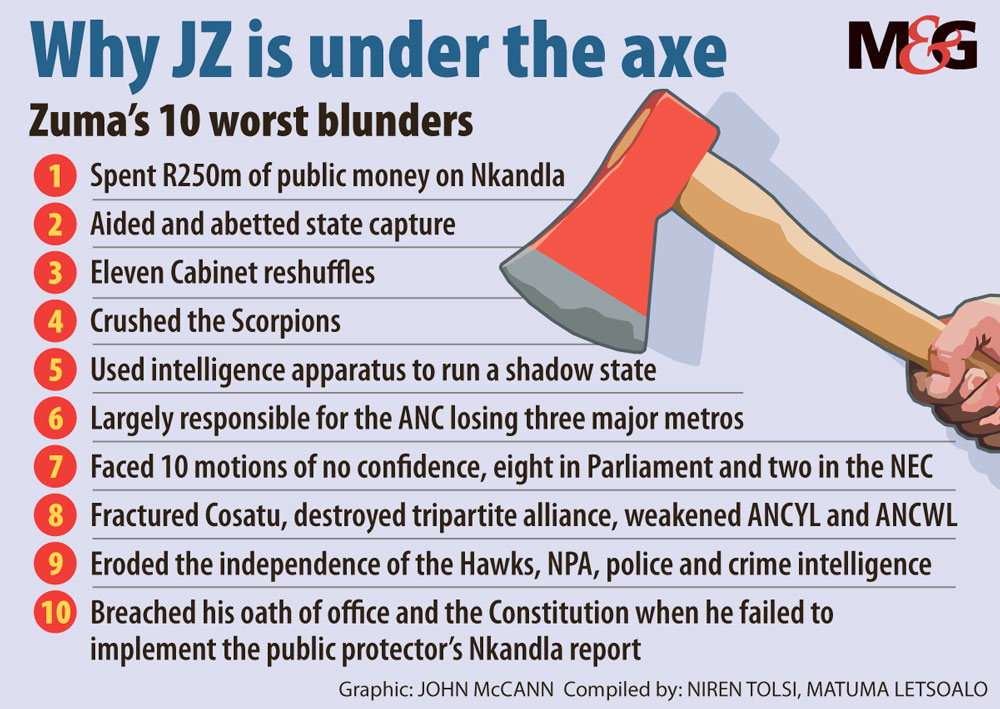

After 10 years and two disastrous terms as ANC president, the great unifier has become the great divider. Large swaths of conference resolutions — from economic transformation to building tripartite alliance unity — stand unimplemented.

Those that have been implemented — the scrapping of the Scorpions, most notably — appear to fit Zuma’s agenda. The past “decade under Daddy” has been more about one individual than about the ANC collective or the welfare of the country.

Likewise the resolution to establish ANC subregions where there were “type B local municipalities”. This ensured that Zuma’s idea of consolidating power in the ANC by conflating state and party into patronage networks became more sophisticated. Regional leaders controlled district municipalities and their largesse, and subregional leaders were able to control local municipalities, creating more room to entrench factions and slates — preferably in favour of uBaba.

The party that Zuma pledged to heal has split twice during his tenure. First the Congress of the People was formed, and then the Economic Freedom Fighters. Both splinters came after the purging of Zuma’s opponents. Some of Mbeki’s backers left willingly. The rest were pushed.

Ahead of the 2012 Mangaung conference, Zuma’s most vocal internal critic, then ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema was booted out. Supporters of the ANC deputy president at the time, Kgalema Motlanthe — who had opposed the expulsion and later stood against Zuma for the presidency — were cast aside like tattered kangas.

The resolution to ensure the “cohesive functioning of the alliance” and the behind-the-scenes hope by labour federation Cosatu and the South African Communist Party (SACP) that their “left” candidate would move government policy in a pro-poor and pro-worker direction also proved a mirage.

The only ones who had Zuma’s ear, it emerged, were businesspeople such as Roy Moodley and the Gupta family.

Despite both the 2007 and 2012 ANC conference resolutions on building alliance unity, the relationship with Cosatu, the SACP and the South African National Civic Organisation has “broken down completely”, an SACP central committee member said. The SACP fielded its own candidates against the ANC in the recent Metsimaholo by-election in the Free State.

The Zumafication of the ANC saw Cosatu lose its long-standing general secretary, Zwelinzima Vavi, after he became critical of the “hyenas” in the Zuma project, who were feeding off the state.

Cosatu itself split. Its biggest affiliate, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa, with some 400 000 members, was expelled. Others followed to form the South African Federation of Trade Unions, now led by Vavi.

Zuma’s two terms have led to the transformation of the ANC national executive committee (NEC) from a collective of national leaders to a coalition of regional mafias. The existence of the “premier league” and Zuma’s influence in the party’s youth and women’s leagues has, to a great extent, ensured the NEC’s inability to act against the president or rein in his self-interest.

Zuma has, since the state capture scandal broke, survived two votes of no confidence in the NEC. Those who led the charge against him — Pravin Gordhan, Derek Hanekom and Blade Nzimande — have been removed from his Cabinet.

These decisions were, according to Mantashe and ANC treasurer Zweli Mkhize, taken without consulting party leaders or its deployment committee. This is despite the 2007 resolution that the ANC must strengthen collective decision-making and consultation on deploying cadres to senior positions of authority.

In deploying cronies, Zuma’s administration has been characterised by stasis and ineptitude — best demonstrated by the South African Social Security Agency meltdown and the distribution of grants caused by women’s league president and Social Development Minister Bathabile Dlamini.

The National Development Plan appears stillborn despite the resolution to strengthen economic planning and implementation across government spheres.

The 2007 ANC conference resolved to strengthen state-owned enterprises and ensure they remain “financially viable”, in line with the ANC’s policy and transformation objectives. Under Zuma’s watch, parastatals have mainly transformed the bank balances of his family and closest friends.

The Zuma government has failed miserably on the land question. Ten years after the ANC reaffirmed a resolution on a land audit and undertook to complete it “within the next 18 months”, it has still not been done. The state still does not know who — including itself — owns what land, and what it is being used for, if at all.

Land reform moves more slowly than Zuma trudging towards his “day in court”. Post-settlement support is inadequate, despite promises to review it. The state’s right to expropriate land for public interest, its promises to fast-track the use of unused state land for public housing and to “review the principle of willing seller, willing buyer” are used for populist sloganeering and little more.

Rather than implement the resolution that the “allocation of customary land be democratised and should not only be the preserve of the traditional leaders”, a traditionalist Zuma has worked to achieve the opposite.

Electorally, two terms of Zuma’s presidency have hurt the ANC. New parties have been birthed from within the ANC, and opposition parties have grown. The ANC lost key metro councils — Johannesburg, Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay — as well as rural councils, and could lose Gauteng and the Eastern Cape to the opposition in the 2019 national elections.

The decade under Daddy has been a disaster for both the ANC and the country.