United Nations’ support for a Limpopo coal and steel plant must be withdrawn as it contravenes green and human rights, say petition signatories

Not long ago, the Highveld Steel iron plant was a place of flames, fire, thunder and lightning. Now, it’s eerie and silent, a site that is slowly being commandeered by the elements.

On one side of the open-air plant are rusted kilns, which, for decades, processed iron ore from Highveld Steel’s nearby Mapochs mine. On the other side is an abandoned two-storey blast furnace, where the ore was smeltered at 1 600°C before it was taken to the steel plant.

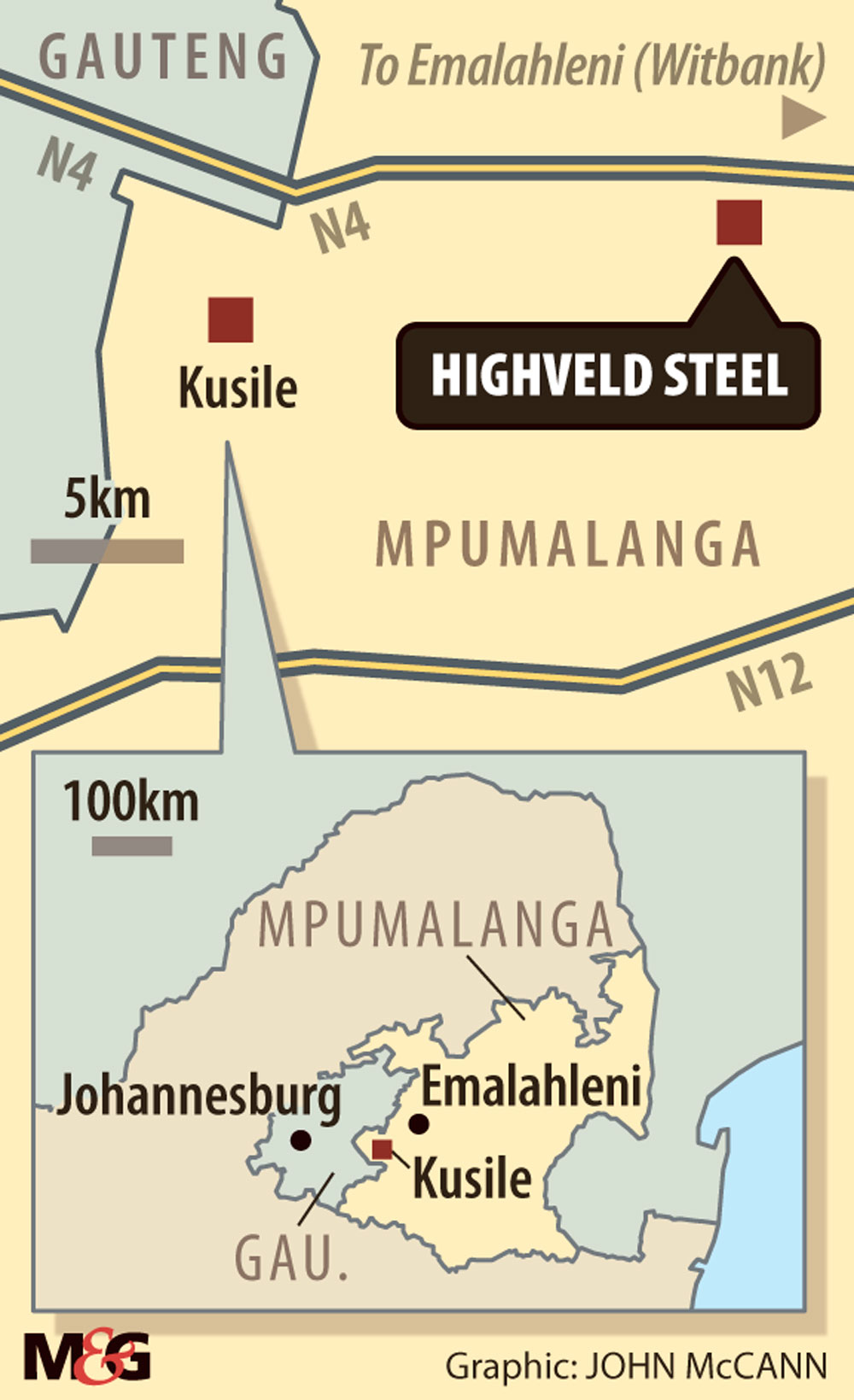

Beyond the site on the horizon is Kusile, which, once completed, will be the fourth-largest coal-fired power station in the world. Despite the fact that Highveld Steel is the only manufacturer of structural steel in Africa and is just 24km down the road, none of its production was used in Kusile’s construction. Apart from the front gate, that is.

After operating for more than half a century, Highveld Steel, once a cash cow for its shareholders and a major employer, closed its doors in February 2016 after seven years of successive losses. A lethal combination of poor management, a sustained downturn in commodity prices and subsidised steel imports from China saw the company being put into business rescue when the shareholders walked away from it.

With the closure went 1 800 permanent jobs and about R320-million in severance packages became due. The business rescue team was forced to move away from steelmaking, if the company was to have any hope of ever making good on its debts.

Left for dead

The Russian-owned Evraz acquired Highveld Steel and Vanadium from Anglo-American in 2007 and for the next two years enjoyed good profits, thanks to high commodity prices, especially that of vanadium.

The huge operation was a one-stop shop. Evraz would mine vanadium-rich ore from the Mapochs mine, process the iron and make the steel that would then be distributed to its two steel mills, which produced steel plate and structural steel which is used in skyscrapers, trains and dams.

But from 2009 onwards the cycle turned and the company made losses year after year. In late 2014, Johan Burger, who was already enjoying an early retirement, was brought in as chief executive in one last bid to turn Highveld Steel around.

“We thought we could turn the operation around and make it more efficient, knowing the state of the steel industry, knowing where we were,” he says.

“The earning in the first quarter of 2015 was positive for the first time in many, many years. But we were overtaken by this wave of debt, of low growth. It was just actually too little too late.”

The new management team was in only its second board meeting when they realised they would be trading recklessly if they did not place the company into business rescue.

“The business needed orders of 50 000 tonnes a month to be sustainable [but] there was a 90% drop in order volumes, with one month seeing just 5 000 tonnes on the books.”

But the power bill and salaries alone tallied R200-million a month and the company was out of cash. At one point, there was just R50 000 in its bank account.

A R150-million loan from the Industrial Development Corporation was only enough to keep the operation afloat for another few weeks. Once one of Eskom’s 10 biggest customers, the utility came within hours of cutting the power to Highveld Steel.

Attempts to sell the company failed and business rescue commenced, the success of which was predicated on funding that was not forthcoming, says Andrew Maralack, the chief financial officer of Highveld Steel.

Burger says: “The shareholder [Evraz] just got gatvol … For a relatively low cost, I believe we could have saved it. The people demonstrated they could make the savings, they could do the efficiencies. But, you know, it wasn’t to be.”

Unrestricted imports

When Highveld Steel went out of business, South Africa was the only one out of 75 steel-making countries that had not implemented import tariffs to protect its domestic steel industry from a glut of cheap steel imports, mainly from China, where the industry has been heavily subsidised by the government.

“China’s economy, in most sectors, is grown through unfair trade practices where they subsidise all kinds of things,” says Donald MacKay, the director of XA International Trade Advisors.

“China clearly are creating jobs in the process but they are also controlling the market. And when you control the market, you get to a point where you control the price. The idea is you take pain now but you are not going to take pain forever,” he says.

In years gone by, the minister of trade and industry, Rob Davies, had often said he would never introduce duties on dumped or subsidised imports from China, MacKay says. “That had interesting impacts on us because, as markets were shutting steel producers out, they were looking for other places to send steel and we were one of those other places.”

Historically, the relationship between the government and local steel producers has not been good. The relationship with ArcelorMittal South Africa (Amsa), which employs 13 000 people, has been particularly acrimonious and in 2016 the steelmaker was fined R1.5-billion, the biggest fine ever, by the competition authorities for anti-competitive behaviour dating back to 2003.

Evraz Highveld Steel, too, was fined R1-million for providing sales volumes to an industry organisation, although it denied being in contravention of competition law.

In the case of Highveld Steel, the state moved too slowly. Only when the cheap imports threatened to bring the entire domestic steel sector to its knees did the government step in, agreeing to some import tariffs to be placed on steel imports. But this protection, benefiting largely ArcelorMittal, has been a bone of contention for downstream businesses that use steel and must now pay a higher price for the product.

The motivation

When you enter the 1 000ha High-veld Steel property, you are greeted by huge structures, rusted and black from decades of industrial exertion. But a closer look tells a story of rejuvenation.

Burger and Maralack are part of the team selected to assist with the business rescue, headed by business-rescue practitioner Piers Marsden.

The easiest way to raise money from Highveld Steel was to scrap it and use the proceeds to pay the creditors. The team estimated this would yield little more than R400-million.

“But a plant of this magnitude would cost tens of billions to rebuild. It literally cannot be redone. So we knew this had to be preserved, even if we were the only ones thinking it at the time,” says Burger.

The primary aim was to preserve the plant’s steel-producing capacity and ensure it was not cut up for scrap. There was the added problem of the creditors, with the employees being first in line, says Marsden.

[Change agent: Johan Burger was brought in to Highveld Steel in a last-ditch bid to turn the operation around. (Madelene Cronjé/M&G)]

“We retrenched them but we didn’t have the cash to pay for it,” he says, adding about R320-million was owed in severance packages.

This debt forced the team to try something different.

A feature of Highveld Steel workforce was its multigenerational nature — workers’ fathers and grandfathers had worked there all their lives.

“But it happens. And you owe them money. You don’t want to walk away from that … therein lies an opportunity not to give up,” he says.

Maralack says: “To restart a plant of this nature, we said this would be in the region of R2-billion. It was impossible at that stage, so we had to come up with innovative plan to produce steel again.”

One of the prize assets was the structural steel mill, which was the first asset to be resuscitated because of the uniqueness of the product, he says. With no support from shareholders or the state, the rescue team had to think outside of the box to find the funding they needed.

Lazarus effect

The first change in thinking was to do with the railway line, which used to bring ore to Highveld Steel. But what if it could take goods from the premises, the rescue team wondered.

“We called the guys from Transnet and asked if we could reverse engineer it,” says Marsden.

With a few adjustments, the rescue team began renting out the rail infrastructure on a rand per tonne basis and enabled local coal miners to use rail, which now takes their product to Richards Bay.

About 300 coal trucks enter the Highveld Steel premises daily and, to date, 1.8-million tonnes have been moved from the site for export.

Next, unused workshops were rented out. For example, one equipped with cranes that can lift 67 tonnes is being used to refurbish dragline buckets — heavy equipment used in surface mining — which used to be transported to Alberton for the same service.

Now there are 21 tenants on site, with several workshops still available to lease. The Highveld Steel canteen is leased to an entrepreneur, who renamed it Khulisa Mandla, and business is booming.

Other facilities are rented out to an operator who provides training for companies — an example of how former cost centres have been turned into profit centres, Burger says.

Some of the land is leased to farmers, with an estimated 700ha more still available. An agricultural college will soon also be set up on the site.

The old dumps — Maralack prefers to call them resources — are also available to be processed for remnants of lime, titanium and steel splatter. External parties are charged per tonne recovered and this revenue is being ring-fenced for an environmental rehabilitation fund.

The team is always looking for opportunities.

Fuel stations may be set up on either side of the highway that runs through Highveld Steel land.

Some of the land is being rezoned for medium-density housing, which would plug into Highveld Steel’s water and electricity allowances.

Income generated by these activities helped the rescue team to refurbish and modernise the structural steel plant. Highveld Steel buys in raw steel billets or blooms from ArcelorMittal for processing long steel, which it sells back to Amsa. About 65 000 tonnes were rolled in the first nine months of operating and the operation now accounts for 10% of the income of the Highveld Industrial Park, as it is now known. This goes to paying creditors, including the retrenched employees.

Regular payments to former employees started in April last year and they have so far received a collective R120-million of the R320-million owed to them, Marsden says.

“If we hadn’t done what we did they probably would have got nothing. But that’s very hard to tell that to someone who hasn’t eaten,” says Burger.

Maralack adds: “We would have been telling this story with more gloat if those people were fully paid off today. We recognise the pain of these people.”

About 200 of the retrenched Evraz workers have been re-employed at the structural steel operation. More than 500 other jobs have been created by businesses renting space.

Community protests over job opportunities at the industrial park induced the rescue team to set up a consultative forum, which meets bi-monthly and presents training and other opportunities to residents from the surrounding area.

“We are thinking slightly differently about the operation now,” says Burger. Reviving it to its former and improved, iron and steel-making glory cannot be excluded, he says.

“It is still something we think can happen, and hopefully will happen, but we are no longer dependent on steel.”

Fighting with fate

Although ArcelorMittal enjoys shareholder support and tariff protections not afforded to Highveld Steel before its collapse, it appears the company is fated for the same end. Last week, it reported continued losses and debt, and will continue to cut costs and look to sell off non-core assets.

According to the National Employers’ Association of South Africa, the steel industry downstream is being severely prejudiced.

And that will end up hurting ArcelorMittal, says MacKay. “If your raw material is going to cost you more than the finished goods [because it’s imported], then it’s only a question of time before people begin to import the finished product [on which there are mostly no tariffs as yet]. Some of that has started to happen.”

But Garth Strachan, the department of trade and industry’s chief director of industrial policy, says ArcelorMittal is too big to fail. The government has stabilised the steel industry but recognises that is not enough, he says.

“We are in the process of developing a longer-term steel strategy, which would have to address problems, including the sustainability of companies such as ArcelorMittal. Steel is absolutely central to the existing manufacturing base of South Africa. And it has to be a backbone of South Africa’s future industrialisation capacity.”

Burger believes the industrial park was the only way to save Highveld Steel at that time and provides a good example of what can be done at other places in the country. “I see a Vanderbijlpark with huge opportunity,” he says.

Inside the enormous abandoned steel plant, the silence is broken by the sound of water dripping down an enormous steel-splattered beam — and an alarm that sounds sporadically.

Deeper within the dark, cool structure Burger points out “bomb alley”, where giant pots called ladles, previously tasked with carrying 70 000 tonnes of molten steel, now lie haphazardly.

“Very few plants like this restart and you can see why. But there’s a first time for everything,” says Burger as he walks out into the light, the wind whipping up the fine iron ore dust at his feet. “You may not think so but one day we will make steel here again.”