Women's perspectives: Nontobeko Ntombela has curated the SOLO exhibition at Cape Town Art Fair that features works by emerging female artists

If we purposefully make space for any group that has been prevented from participation and representation — pushed to the margins, or erased altogether from culturally-validated forms of public self-representation — we have to speak about why such extraordinary efforts are necessary. Inevitably, there will be those who do not believe that historical erasures exist.

Purposefully making a space to include women’s — particularly black women’s — artwork and their voices in discussions that pertain to the social, economic, and political spaces in which art-making, art-displaying and art-selling exist, always brings about anxieties that insidiously and systematically resist changes to the status quo.

Thus, a curator cannot set out to explore the artistic practices of emerging and established women artists, to offer “different perspectives of the widespread socio-political issues faced by women, while also highlighting their contribution to the art world” without dissenting voices in the background.

These concerns are especially pertinent when we are speaking about correcting erasures at an art fair. After all, it is a context that is meant to be an inviting and pleasurable commercial space to the consumer — not one that makes the public have to think too hard about difficult histories or, worse, the difficult present.

Nontobeko Ntombela, as curator of this year’s SOLO exhibition at the Cape Town Art Fair, is confident that the fair also offers a “space to conscientise the general public about critical debates with which artists are engaging in their work, but also to make possible serious conversations a commonplace and part of the everyday”.

Along with the usual gallery stands that are a central part of the art fair business, SOLO operates in concert with several other sections focused solely on emerging artists. Ntombela’s choice, to focus on women artists, “is aimed at presenting varying perspectives of the widespread socio-political issues faced by women in both public and private spheres, while also highlighting the contribution of women to the art world”.

For her, given the “prejudice that women face on a daily basis and the current public uproar on femicide” creates the need to “turn the spotlight on women in the arts, particularly women of colour”.

Violence targeted at erasing the bodies of women tells us that their physical, emotional, and political and intellectual labour remains a threat. It causes enough public anxiety that they must face the danger or erasure, be it through physical violence or through less obvious ways.

Ntombela notes that Innovative Women in 2009, “caused a public stir when the then Arts and Cultural minister Lulu Xingwana walked out of the exhibition claiming the exhibition was pornographic”; the cause of offence was Zanele Muholi’s work, depicting intimate, beautiful, and alluring scenes between lesbian women. This occurred in a context in which lesbians are being raped and murdered, and in which the history of same-sex love is being violently cut from South Africa’s narrative.

More recently, Ntombela reminds us, that the Our Lady exhibition at the National Gallery revealed glaring problems underlying the ways in which elite art spaces and curatorial practices continue to violently excise women artists from the public consciousness. In this case, despite publicly advertising itself as an exhibition that celebrated “empowered female capacity”, art by men made up 75% of the works chosen by curators — only three black women were represented.

Especially bizarre in a exhibition meant to celebrate women was the inclusion of Zwelethu Mthethwa — who was then on trial (and eventually convicted) for the brutal, CCTV-recorded murder of 23-year-old sex worker Nokuphila Kumalo — without any acknowledgement of his involvement in a violent crime against a woman.

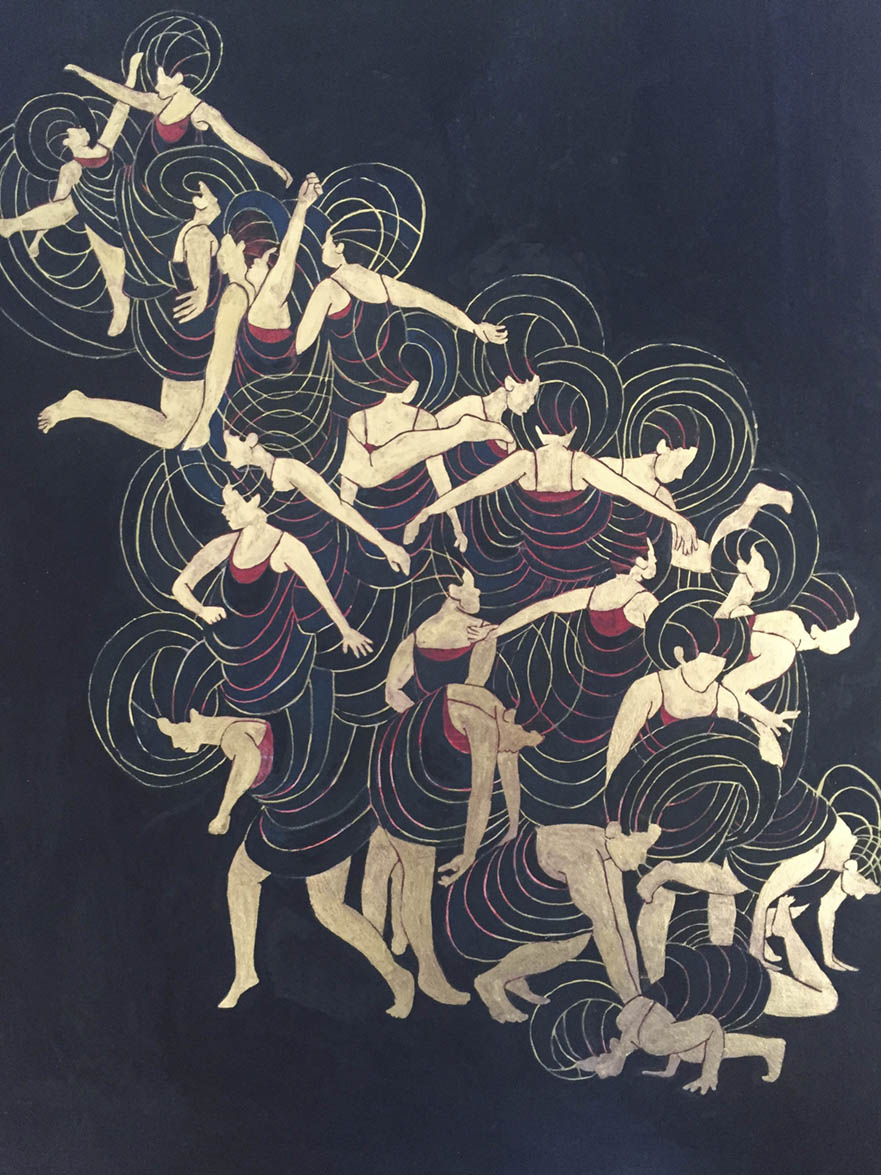

[Kimathi Mafafo’s ‘Twisted Fall I’ is amongst the works curated by Nontobeko Ntombela]

Ntombela points out that women artists have not only contributed to the arts, but have been “great catalysts when it comes to fostering debates that raise awareness about the oppression of women”. She lists off the names: “Zanele Muholi, Dineo Bopape, Nandipha Mntambo, Tracey Rose and Berni Searle to name a few have been catalysts in drawing attention to this space. Their work has challenged historical misrepresentations” and, at the same time, propelled a deeper public understanding “of gender and sexuality, among other things”.

This iteration of SOLO, which Ntombela titles From No Fixed Place, stresses the point that the selected artists speak beyond surface-level representation of gender and its relationship to aesthetics. Instead, each artist in SOLO situates themselves in the critical position of the storyteller, exploring “the alter-self — as a spiritual being, a myth, a sexual being, a history-maker, a part of the cosmological world, a form-landscape, a cityscape, an archaeological site, a vessel, a body, and so forth”.

[Botswana born artist Pamela Phatismo Sunstrum’s ‘Les Oreides’]

They tell compelling stories about what it means to be living in a world in flux as beings informed by history and the present.

Ntombela’s selection of artists come from a range of geographical locations: Uganda’s Stacey Gillian Abe, Italian-Senegalese artist Maimouna Guerresi, Keyezua (a binational of Angola and the Netherlands), Botswana-born Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Jamaican-American artist Renee Cox, and South Africans Lhola Amira, Kimathi Mafafo, Ingrid Bolton, Lucinda Mudge, and Buhlebezwe Siwani.

[A part of Ntombela’s selection includes South African artist Lhola Amira’s iYahluma ]

Attaching these artists to a particular nation — to mark them as a product or representation of the nation state — isn’t possible. They have moved, and have been moved, by larger geopolitical upheavals that imprinted themselves on their different heritages.

The 10 artists use a range of materials and form, exploring the aesthetics of being unmoored from both traditional categories — like the nation, gender, or formal expectations of artists. They explore commonly-held notions of identity that not only limit our views, but also what we expect of an artist. Finally, the works are also part of the methodology of each artist’s spirituality, themselves modes of consciously directing complex, amalgamated selves.

In response to these shifting socio-political tectonic plates, each artist explores the multiple lives that are essential to who they are. As Ntombela puts it, her curatorial focus is on “how these artists develop the concept of the alter-self — or what some may refer to as an alter-ego, alias, or pseudonym —that becomes recognisable through repeated motifs”. This focus on alter-self allows artists to destabilise categories that “locate” and fix identity.

In many of the works we will see that there is a “repeated use of the same human figure, repeated personified objects, or — in the case of performance art — a repeated ‘appearance’ of a known ‘other-self’ or spiritual being through the artist’s own body”. Through their use of alter-selves, the artists are able to layer “irony and metaphor to tell stories” and explore the contradictions of “the realities” of living in their particular locations, whilst allowing them to explore “imagined” and perhaps more ideal worlds.

Here, the use of “irony and metaphor enable artists to speak in multiple voices; it can be seen as a form of agency that artists use to define the ‘place’ (as opposed to being defined by the places)”. This, Ntombela is careful to point out, “is not about denying how their identities are tied to their work, but rather, how the alter-self is developed through the use of personal or popular iconography in their choice of medium and subject matter”.

Ntombela honed her skills as a curator training at Asiko, the roving curatorial programme run by Lagos-based curator, writer, and educator, Bisi Silva. She was first invited as a faculty member of Asiko in 2015 for the Maputo iteration (as well as in Addis Ababa in 2016 and Accra in 2017), which arrived at a critical juncture in her life.

She wanted to engage with questions of teaching curatorial practices through workshops and residencies, rather than formal, university spaces — which, in South Africa, had favoured pipelining white students to the few employable positions.

Through her participation in three different programmes, she “got to understand the workings of different arts economies”; and the “research question about sites of knowledge and how to theorise and analyse creative practices of Africa from an African perspective” arising from discussions also “found its way into [her] PhD as a chapter”, and into her everyday practice as a curator.

She recognises the significance of her mentors and colleagues — particularly N’Goné Fall, Bisi Silva, Patrick Mudekereza and Khwezi Gule — in shaping her practice. She also gains from the relationships she builds from working with artists.

Her approach — to present artists as narrators and critics engaging with questions essential to our contemporary lives — allows them to operate from a position of agency and freedom, to circumvent traditional boundaries. While the notion of artist as storyteller is not new, notes Ntombela, it is a position that is “usually reserved for the male western artist who is seen as a flâneur, a genius who operates without any historical burdens”.

To “curate a show that focuses on women artists solely” demanded that she moved with sensitivity. Her approach critiques and circumvents gendered expectations of “female” artists particular to our time and to the location in which the artwork is being shown, as well as her own — at times unacknowledged — constructs.

We, as audiences, can only follow suit.

M Neelika Jayawardane is associate professor of English at the State University of New York-Oswego. She is a recipient of the 2018 Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant for a book project on the Afrapix photo agency