Iqbal Survé

Abortion has been legal in South Africa for more than 20 years. So why do women continue to flock to illegal abortionists and put their lives in their hands? The answer is probably more complex than you’ve been led to believe because even in the 21st century, we’re still not talking about terminations.

And our silence is deadly.

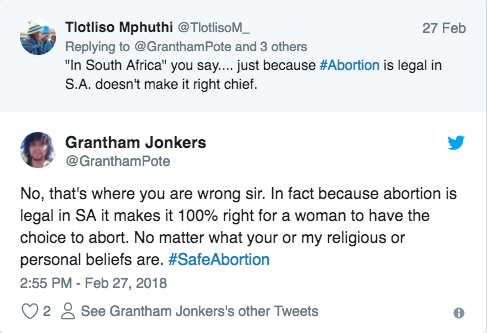

This week, Bhekisisa brought together journalists, doctors, activists and women to talk about #SafeAbortion and things got real. So if you thought you knew everything there was to know about abortion in South Africa, think again.

1. Women’s bodies — in particular, black women’s bodies — have a long history of being policed in South Africa, Eddie Mhlanga, the Mpumalanga health department’s specialist obstetrician and gynaecologist points out.

2. But then democracy happened, and women such as Albertina Sisulu and Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma made it into Parliament. They had their sights set on putting an end to the apartheid legislation that was killing black women. Mhlanga helped pen the 1996 Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act. Sisulu, Dlamini-Zuma and others made sure it passed.

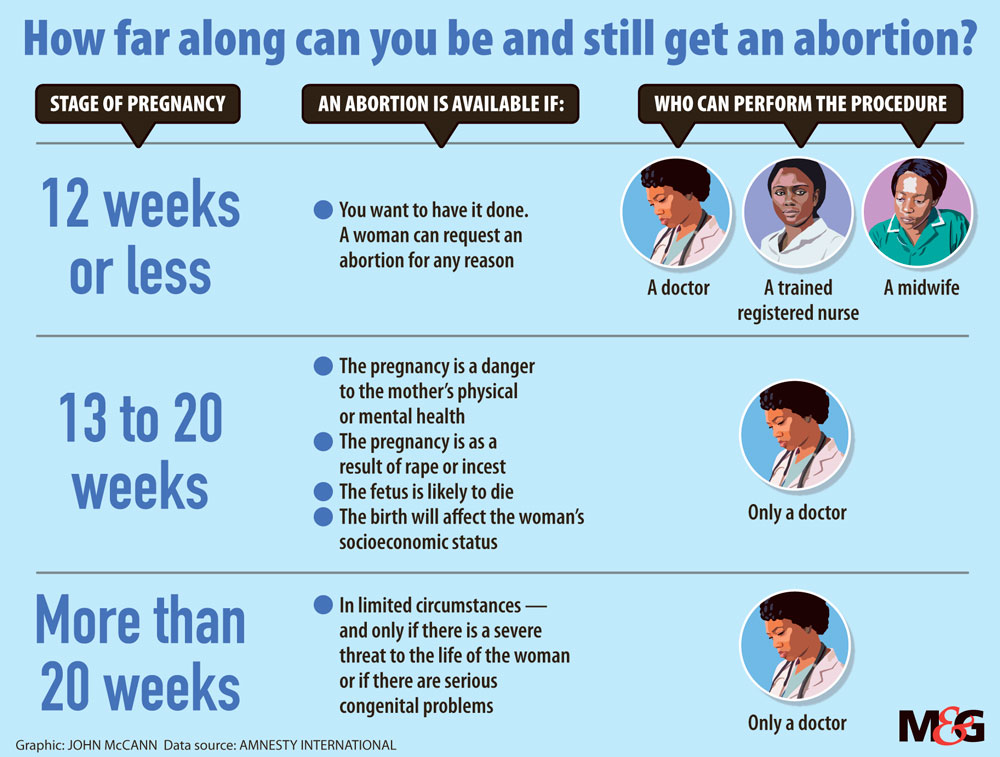

And here’s what women are entitled to today:

3. But more than two decades later, there’s a lot standing in the way of people with uteruses and their right safe, legal abortions. Sometimes it’s a lack of public health facilities. A recent telephonic survey by Bhekisisa found that less than 5% of public clinics and hospitals offered the procedure.

Even when services are nearby, the very people who are legally supposed to provide the services go to great lengths — and even heavy-duty hardware — to make sure women can’t use them.

And firing them isn’t always an immediate option.

4. When it comes to bullying women out of seeking services or just plain shutting them down, everyone from a hospital head to a clinic cleaner can play their part, says Indira Govender. Govender is a doctor from rural KwaZulu-Natal who has worked at a regional hospital, performed terminations and treated women’s complications from backstreet abortions.

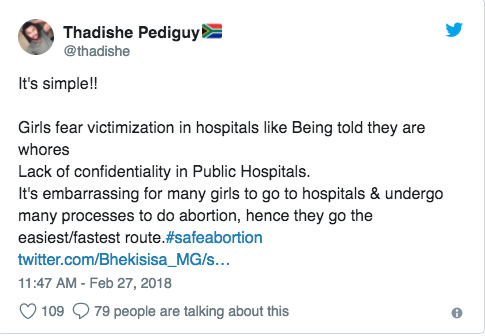

5. Even when government clinics and hospitals offer safe, free terminations, the humiliation women endure to get them from staff is enough to send them to those illegal abortionists anyway.

Don’t believe it? Here’s what one health worker said to us last year:

6. And that shaming comes from a deep, dark and very gendered place.

7. Sometimes, the stigma hurts worse than the procedure. This, rather than the termination, haunts you because those voices that call you names for exercising a Constitutional right begin to ring in your head, says Grace who underwent her first termination at 17.

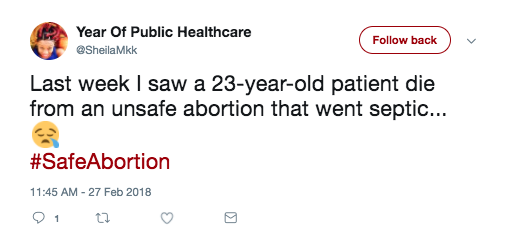

8. Despite the hype, no one really knows how many women die at the hands of illegal abortionists each year. Not even the national health department, admits the department’s director for women’s health and reproductive health and genetics, Manala Makua.

But this wasn’t always the case.

9. By the health department’s flawed calculations, tens of thousands of women should be dying because of illegal abortions and not even that hyped up number has sparked a national outrage, Mhlanga points out. There might be a reason for that, he says.

10. Meanwhile, the real causalities are mounting, unnamed and uncounted.

11. But we can stop this by cutting the stigma out of #SafeAbortion and by training more and different kinds of health workers to provide it, Mhlanga says. This includes using the country’s newest type of health worker, clinical associates. These are health professionals trained at a higher level than nurses, but ranked lower than doctors. They are not permitted to work without a doctor’s supervision.

12. So whatever your views, remember it’s not your choice what a woman does with her body. The law’s made that decision already.

13. And a choice can make all the difference:

Grace says she wouldn’t have been able to finish school and get a job if she had two kids:

“I moved beyond being the typical girl from the township who gets pregnant. I made it. I made it out of Soweto and that poverty and patriarchy.”