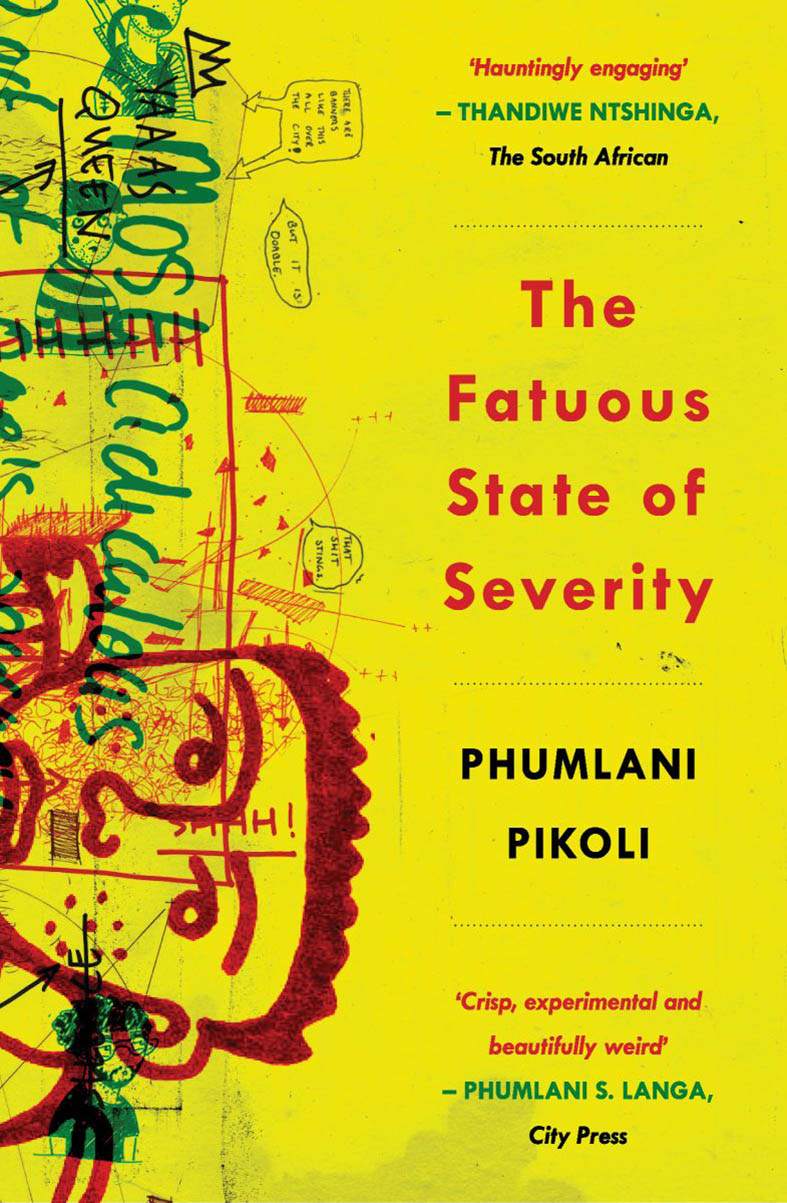

Intimacy: Writer Phumlani Pikoli’s collection of short stories deals with the contemporary South African reality in a way that is absurdist and

It took me a lot longer than it should have to get through Phumlani Pikoli’s collection of short stories. The Fatuous State of Severity, the jigged-up mainstream version, comes in at precisely 150 pages. But don’t let its pint-size fool you, to borrow from Joe Higgs. There’s lots of razors to be stepping on here with your bumbo klaat ways.

Here’s the thing: The Fatuous State of Severity — the title pretty much summing up the upside-down state of our existence as a society — is not quite a solo project, with Pikoli stuck in a corner shooting out shrapnel from his brain as an act of public menace.

There’s shrapnel, blood, balls and cum aplenty, but there’s also a palpable search for the self, and a rallying of a community of other present-day iconoclasts.

[The Fatuous State of Severity: Phumlani Pikoli’s collection of short stories (Pan Macmillan)]

Watching the videos that Pikoli and his squad assembled to go with the book of short stories — because, you know, in true millennial fashion, the thing can’t live in only one sphere and die of a lonely heart — you start to get a sense that a new generation is here and maybe we, the predecessors, struck out at our turn at bat.

One can’t help but admire Pikoli’s vulnerable cockiness and the punk attitude driving him and cohorts such as Nas Hoosen, Fuzzy Slippers, Rofhiwa Maneta, Lerato Mbangeni, Tseliso Monaheng, Nolan Oswald Dennis, Lesedi Rudolph and Carren Aranes, to name but a clutch of them.

Some members of the squad crossed paths during what he calls “the Mahala days”, when some of them were literally writing for free on that cultural website.

Pikoli calls the “fatuous state of severity” a “state of mind I had come to occupy while recuperating from a depressive episode at a psychiatric clinic … a liberation that helped me launch myself on to the publishing radar”.

He doesn’t care much for this origin story, because that kind of puts the book in the corner dladla of the ghetto where mental illness is fetishised. “I’m not depressed because I’m a writer,” he says in the foreword. “Nor do I write because I’m depressed. I simply enjoy playing with words and have a knack for putting them in the write order. (I’m also dyslexic.)”

Checking out the reading sections of the videos, my stomach knotted up for various reasons. Maneta brings an intellectualism to the dissection of Pikoli’s aesthetic, simply labelling it absurdism with a charismatic, flippant flourish. Mbangeni chokes in discomfort at having to read Tumblr, a brief but affecting story that mines shock value and social media-driven angst to examine our empathy for difference and detachment. I suspect I may have read too much into it, because the final line upends any clear moral to an already bizarre story. Her unease, in this case, becomes a stand-in for the peeling back of our collective conservatism.

Aranes, reading from My Beautiful Little Boy, chokes me up because of the human quality of the entire setup. The ambient sound in the background enhances the feeling that Pikoli does not walk alone, cutting to the heart of a story about an older brother bonding with his younger sibling and hipping him to the wicked, racist ways of the world.

There’s a vulnerable quality to the sound of Aranes’s voice that makes her seem perfectly cast for the part. Pikoli’s writing voice here, a pitch-perfect rendering of two black boys bonding, somewhat alienated from the mores of their new environment, is emotive on multiple levels. The story is apparently a composite of Pikoli’s momentous encounters with his various siblings.

Meeting him for the first time last week, I waved this story in his face as evidence of him being a marshmallow-hearted whippersnapper masquerading as a gonzoesque rebel. He, instead, pointed me to the filth, smut and slime of it all.

In parts, reading the book feels like being in the company of a friend who is always trying to play annoying tricks on you, while putting you on to some game. In Biko, a trippy story set on a Mozambican beach (Tofo, to be exact), Pikoli seems, in part, to be concerned about the hypocrisy of the South African black middle-class condition, our lingering bouts of exceptionalism and how they play out in public as we hop over the border for some cheap thrills.

Pikoli’s numerous dances with tone, positionality, technique and moralism throughout are not merely gymnastics for the sake of it. But exactly what the stories mean is for you to figure out.

Audience, for example, sees a black athlete named Ezekiel give a bizarre acceptance speech about being tied to the back of a car, redneck style, and made to jog from Jo’burg to Pretoria behind it. It could be about the performative nature of the discourses surrounding black excellence nowadays, but what the fuck do I know?

So, how does The Fatuous State of Severity read as a whole? There are several points to consider. Pikoli wrote the book pretty much in two stages, with this, the second version, augmented by stories such as Cargo, Seasons Change, Biko, Deactivate and Blogging 4 Likes several months after the first flurry of stories.

Something he also intimated to me was that the book was written as if to his 15-year-old self. When he first said this, I took the statement as a cop-out that allowed him to be indulgent with stories in which he seems more infatuated with his own prose and the release of writing than with expanding his palette and possibilities for more trenchant commentary.

But The Fatuous State 2.0 is a much better product than the first incarnation because Pikoli is willing to leave the urchinlike preoccupations of writing for the sake of flexing — which certain parts of Fatuous feel like — for stories in which he is finding more meaningful, and no less artistic, ways of grappling with the South African condition.

The unflappable, shoot-from-the-hip contrarian may be on his way out, but truth be told, I don’t know him like that.

I had the unfortunate honour of reading Seasons Change, Pikoli’s short story about saxophonist Simon Molefe, in the week Bra Hugh Masekela left the planet. Lines like the following passage had me wondering whether Pikoli had dared to say the intractable: “As the years unfolded and he became more celebrated, in the new world that he had ‘helped’ shape, a strange nostalgia took hold of the country he had ‘helped’ create. A reminiscing of a bygone era to which he had given an impeccable soundtrack. His lullaby melodies, with their upbeat phrases, made it into the annals of optimism acquired through an exchange of cultural pleasantries.”

Pikoli swore, when confronted, that there was a Simon in every pub in every city, making this book a quite a singular capturing of the South African zeitgeist.