Pemba in northern Mozambique has seen a surge of new arrivals in step with investments to exploit off-shore gas deposits.

Natural resources are often thought of as a curse in developing countries, slowing economic growth rather than driving it. But new results from our research show that discoveries themselves – before extraction happens – have their own economic consequences.

Our research shows that countries where natural resources are discovered are inundated with injections of capital, much like boomtowns during a gold rush. Giant and unexpected oil and gas discoveries act as news shocks, driving the business cycle by triggering foreign direct investment (FDI) bonanzas. Across countries, we find that FDI inflows driven by new projects in new industries increased by 58% in the two years following a giant discovery.

READ MORE: Poor Mozambicans accuse Sasol of bleeding them

We illustrate how this works using Mozambique as a case study. Following a prolific gas discovery in 2009, foreign companies came pouring in and FDI ballooned off the chart. By our calculations 21 500 out of the 25 500 created by FDI in the five years following the first giant gas discovery in 2009 could be due to the discovery.

Our research upends conventional wisdom that the impact of new resource finds, such as gas, only have negative effects on the economy. Our results suggest that discoveries may lead to simultaneous foreign direct investment in many sectors, possibly diversifying economies and increasing capabilities and thus providing a window of opportunity for a growth takeoff.

This is important because it opens the door to policies being developed that exploit the early gains that can accrue from natural resource finds.

Mozambique’s offshore finds

Mozambique’s offshore natural gas discoveries in the Rovuma basin since 2009 have been nothing short of prolific. They are now valued at approximately 50 times the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

While these gas fields are still under development, data from fDiMarkets – a branch of the Financial Times Group that collects and tracks FDI projects around the world – suggest that foreign companies moved in right after the first discovery in a multitude of industries. These companies created around 10 000 jobs across the country in the following three years.

In 2014 alone, the discovery attracted $9-billion worth of FDI. FDI inflows boomed from 2010 onwards. In 2012 Mozambique received 15% of all sub-Saharan African FDI. In 2013-2015, FDI amounted to 70% of the country’s average GDP, the highest share of all African countries.

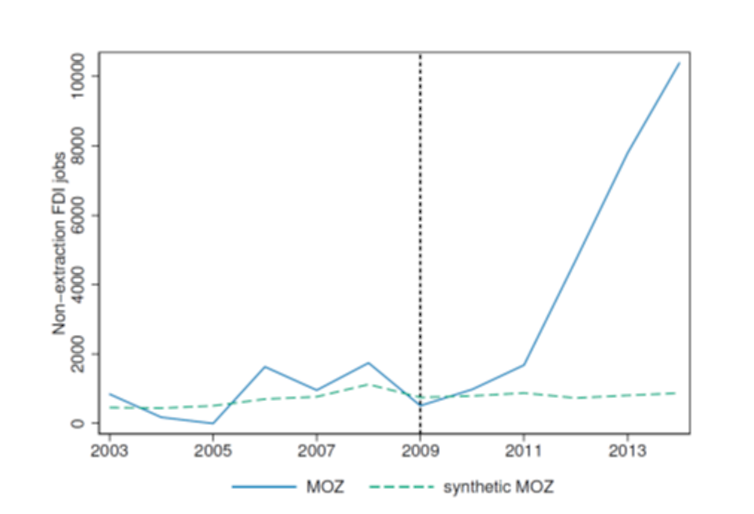

Analysis suggests that none of this would have come in without the gas discovery. And very few jobs would have been created. A comparison of the weighted average of other developing countries with no discoveries shows that if Mozambique had not discovered natural gas, the number of jobs created by non-extractive FDI would have remained flat at around 1500 per year.

The FDI effect of the Mozambique gas discovery. Note: The MOZ line is the estimated number of jobs created by FDI projects, as reported by fDiMarkets. Synthetic MOZ is a synthetic counterfactual – a weighted average of FDI jobs in non-OECD countries with no discoveries that mimic Mozambique until its first large discovery in 2009.

The FDI effect of the Mozambique gas discovery. Note: The MOZ line is the estimated number of jobs created by FDI projects, as reported by fDiMarkets. Synthetic MOZ is a synthetic counterfactual – a weighted average of FDI jobs in non-OECD countries with no discoveries that mimic Mozambique until its first large discovery in 2009.

One new FDI job creates an extra six

Our study also measured direct and indirect job-creation stemming from Mozambique’s investment boom. We did this by linking projects from the fDiMarkets database and data on firms from the country’s 2002 and 2014 firm censuses to employment outcomes across districts, sectors, and periods. Data from the country’s 2002-2014 Household Budget Surveys was used.

Our estimate suggests that for each new FDI job, an extra six were created in the same sector in the same district. This is because newly arrived foreign companies might demand services such as catering, driving, and cleaning services, as well as services from local law firms and consultancies experienced with the economic and legal environment.

Moreover, newly created FDI jobs are likely to be associated with higher salaries. Research elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa has shown that foreign-owned firms pay higher wages to non-production and managerial workers. They also offer more secure – or less temporary – work.

Thus, these jobs are likely to increase local income, and in turn, demand for local goods and services. For example, the multinational’s employees might increase the demand for local fruit and vegetables, as well as for services such as housing, restaurants, and bars. This increase in demand is likely to be met by local businesses, creating more jobs and multiplying the initial number created directly by multinationals.

Our results also point to other interesting aspects of the extra jobs created. This includes the fact that around 55% are informal, that around 65% are taken by women, and that only workers with at least secondary education benefit.

To better grasp the magnitude of the multiplier effect of FDI, we asked: if we removed all foreign direct investment projects from Mozambique in 2014, how many jobs would disappear? This includes all the jobs directly associated with incoming investments (131 486 jobs in 2014) but also all the non-FDI jobs due to the multiplier.

We find there would be almost 1 million fewer jobs, out of a total of around 9.5 million jobs in Mozambique. The drop would be especially large in the manufacturing sector and in the capital of Maputo, where more than half would disappear.

Facing reality

Of course, economic growth and diversification do not automatically follow from a large discovery. The Mozambique foreign investment bonanza occurred while the government accumulated an unsustainable level of debt, and many of the FDI projects may only have short-run effects.

This has happened before. For example, a foreign investment boom in Tete province in northern Mozambique went from El Dorado to nightmare when a coal project failed to materialise in 2014-15. This prompted Rio Tinto to sell its $3.7-billion coal business in the country for $50-million.

Additionally, the economy is still reeling from a debt scandal that led the International Monetary Fund to cancel its funding for Mozambique in 2016.

Even so, foreign investment bonanzas stemming from natural resource discoveries do provide an important economic growth opportunity, and the FDI effect needs to be considered when analysing the effects of natural resources on economic development.

Gerhard Toews, Post-doctoral researcher, Oxford Centre for the Analysis of Resource Rich Economies, University of Oxford and Pierre-Louis Vézina, Assistant Professor in Economics, Departments of Political Economy and International Development, King’s College London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.