Divorce: After her husband’s release from detention

First, the facts: regardless of what Euro-American pundits or obituary writers conclude about Winnie Madikizela-Mandela — or what some white (and some black) South Africans say around the braai — she was a hero to the majority of South Africans, and still is. Just witness the spontaneous outpouring of visitors and vigils at her home in Soweto and around the country.

Various people and political movements have long appropriated Winnie Madikizela-Mandela as a symbol. Her death intensifies this.

For a long time, depending on your point of view, Madikizela-Mandela served as an extreme militant or radical liberationist. She was contrasted with Nelson Mandela’s “reasonable” conciliatory stance towards whites and capital at the end of apartheid.

Such comparisons are now, as they were then, unhelpful. They also serve conservative ends. Those who make them conveniently forget that Nelson Mandela went to prison for advocating armed struggle.

Although some headlines sought to relegate Madikizela-Mandela’s significance to that of “Madiba’s former wife”, she was a major leader of the struggle in her own right and developed a political identity independent of her former husband.

The ANC claims Madikizela-Mandela as part of its more centrist orthodoxy. But it is also the case that, despite ANC leaders now lining up to eulogise her, many in the organisation never liked her, didn’t know what to do with her or were long at odds with her brand of radicalism. Thabo Mbeki’s interview in the days following her death provided a glimpse into that viewpoint.

Outside the ANC, Madikizela-Mandela still provokes strong, contradictory reactions: the opposition Democratic Alliance leader, Mmusi Maimane, reading the political mood, said “she was principled and stood up for the truth”. Young black women, for whom Madikizela-Mandela was a feminist black icon, photographed themselves #AllBlackWithADoek, and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) declared her “the first woman president South Africa never had”.

By contrast, Paul Trewhela, a political prisoner who edited the underground journals Freedom Fighter and Searchlight South Africa but left the South African Communist Party and today is ideologically closer to the DA, compared her with Hitler and Stalin. An obituary by news agency Reuters combined an honorific with an old slur from Britain’s right-wing tabloid press: She was “mother, then mugger” of the nation.

However you feel about her, she led a big life that intersected with almost every major current of recent South African history. Engaging seriously with that life is a way of engaging seriously with history. Done properly, it could help us to understand not just how South Africa got here but also where we are going.

The country faces a long overdue attempt to resolve the land question and deepening class and racial inequalities. Understanding Madikizela-Mandela’s activism might help us through the quagmire.

Understanding her struggles would mean avoiding the tendency to create new silences about how the struggle unfolded, its patriarchal character, or its strong-arm tactics that at one time seeped throughout the movement with devastating consequences.

There has been an unfortunate tendency in public life to silence complex discussions about Madikizela-Mandela’s political life. On the right, people who believed the apartheid propaganda about her, or those who are invested only in her weaknesses and faults, gloss over her heroic actions. By the same token, those on the left who wish to push back against the critiques neglect the full range of her actions. It becomes a zero-sum game.

Madikizela-Mandela became politically aware as a child in rural Transkei and was involved in political work as a trainee social worker in Johannesburg after she moved there. But it was her marriage to Nelson Mandela, then already a veteran ANC leader, in 1958 that thrust her into the national (and international) political spotlight.

After only one year of marriage, Nelson Mandela went on the run. Shortly afterwards, he went to prison, only emerging more than 29 years later. From then on, the mainstream framing of Madikizela-Mandela characterised her only in terms of her relationship to Nelson Mandela; she existed to “keep Nelson Mandela’s memory alive”. This required that she lived up to the stereotype of dutiful, waiting wife.

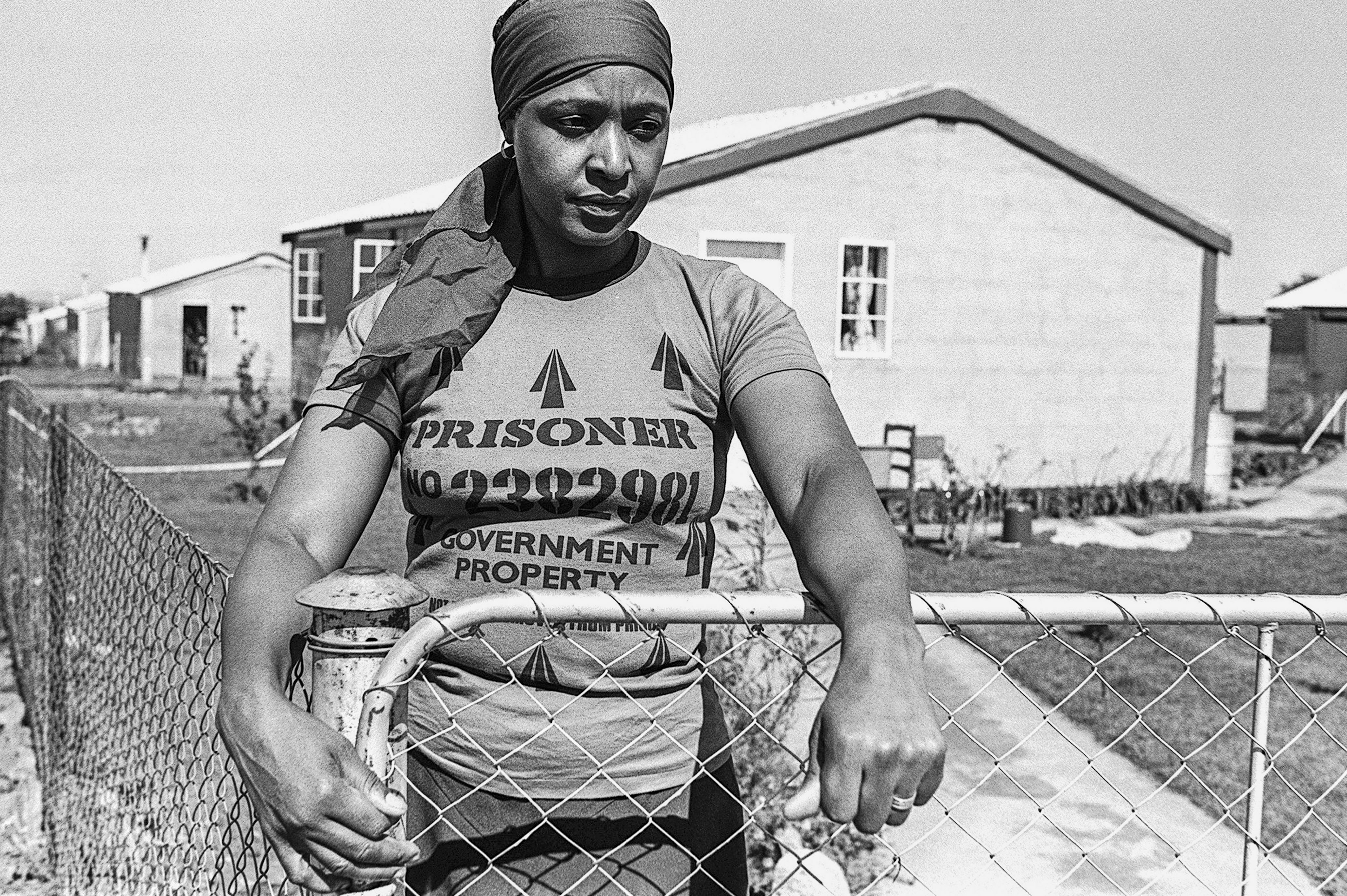

[Loyalty: Soon after their marriage, Nelson Mandela was arrested. In his absence, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela was sent into exile in Brandfort by the apartheid security police. (Peter Magubane)]

Instead, over the next two decades, Madikizela-Mandela emerged as probably the most visible leader of the resistance alongside Steve Biko. And she transcended Mandela and the ANC in the process. Her rise coincided with the decline of the ANC, when its activists were subjected to bannings, imprisonment and exile and ageing between 1964 and 1976.

While the party took some time to get back on its feet, Madikizela-Mandela proved adept at sensing the changing political currents and crossed political boundaries. She worked openly with Black Consciousness activists — whom the ANC leadership in exile despised — and provided open support and solidarity to activists leading the 1976 student uprising, so much so that the government blamed her principally for the uprising.

Her reward: she was first detained and then, in 1977, banished to Brandfort, a small town in the Orange Free State. But instead of cowering, Madikizela-Mandela radicalised the town’s black residents, flouted the rules of her banishment and recruited combatants for the ANC’s armed wing.

She did all this in the face of constant harassment, banning, imprisonment, nearly 18 months in solitary confinement and torture. When reviewing her life, one is struck by how painful and lonely banishment was for her, as a woman, a wife and a mother.

She wasn’t as revered as Mandela but was subjected to similar acts of brutal punishment and humiliation, meant to strip her of her dignity.

What also stands out about this period is how she openly taunted and challenged the state and its agents, police and spies. Go back, look at film footage. There are extraordinary recordings of Madikizela-Mandela serving as a pallbearer, carrying the coffins of activists. This act is usually reserved for men. The effect on people was remarkable. It still is — on women, especially.

One effect of this was the challenge she represented to the ANC about what a woman should be or do in the context of political struggle or in social movements, in terms of challenging patriarchy. This is why she became a hero to feminists. As a black woman she also represented a challenge to white liberals and the apartheid regime, striking fear in the heart of white patriarchy.

This is the Winnie — the rebel who didn’t care much for the niceties of politics or what her opponents thought of her — that her admirers and supporters want us to remember. This image resonates strongly with student movements such as #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall, and the causes of black youth and the EFF.

As for the ANC, it wants to use Madikizela-Mandela’s memory to contain, manage and corporatise political radicalism for electoral purposes and, at the same time, consign militant ideology to the past.

It is what happened to Madikizela-Mandela after 1986 that divides opinion.

In the very short period between 1986 and 1989 her politics took a dramatic turn after she returned — in defiance of the police — from Brandfort to her house in Soweto. She had to reinvent and reinsert herself in a newly configured political world.

While she was in Brandfort, things had changed somewhat for the better for resistance politics. The United Democratic Front, founded in 1983 to oppose apartheid reforms, had transformed into a national resistance movement inside the country and was operating openly.

In 1985, black trade unions — taking advantage of reforms to labour laws — had formed a national federation, Cosatu. The result was the first real mass movement against apartheid since the 1950s. More crucially, the terrain of struggle had shifted. Politics was no longer reliant on charismatic individuals, like Madikizela-Mandela, who often acted alone. Even the ANC in Lusaka wanted in, lest they become irrelevant.

There was now a new generation of leaders operating in a mass movement. There were literally thousands of Madikizela-Mandelas, radical and throwing themselves at the regime fearlessly. They led countrywide boycotts over rent, over conditions in schools, over sham elections and they did so openly carrying ANC flags and adopting the Freedom Charter. This new form of organisation also, crucially, demanded co-ordination and accountability. They had structures and meetings.

During this period, Madikizela-Mandela became associated with a new kind of politics, one that combined personality and militarism and little accountability. As the needle shifted, she became more militant still. She started to dress in military-style garb and moved around with bodyguards.

[Soldier: Madikizela-Mandela became associated with a hypermasculine, militaristic brand of politics. She donned military garb and spouted violent rhetoric. (Adil Bradlow)]

One consequence of this political posture was, sadly, that she began to oversee and embolden the Mandela Football Club’s thuggishness. The gang lived under her roof and she provided them with political cover. They terrorised her neighbours in Soweto and revenge killings — which saw the club acting as a “court” to hear family disputes and deliver “judgments” and “sentences” — kidnapping and, eventually, murder, became their calling card.

They played little football. They decided who was a traitor and who was not. This led to the death of 14-year-old Moeketsi Stompie Seipei and probably that of the (still unsolved) murder of Dr Abu Baker Asvat, a longtime associate of Madikizela-Mandela and known in Soweto as “the people’s doctor”.

Ironically, it was the hypermasculinity of the Mandela Football Club that was so ruinous in those dark years.

Madikizela-Mandela was not alone in being associated with this style of politics. Many male political figures in the ANC dabbled in this brand of militarism too. It is perhaps this singling out of Madikizela-Mandela that irks her supporters and defenders. They, including some feminists, argue that Winnie was singled out for criticism and sanction because she was a woman.

The 1980s resembled a “dirty war”; the National Party government didn’t contest it by parliamentary rules. Responding to apartheid’s brutalisation demanded similar dirty tactics. The ANC called for South Africa to be made “ungovernable”. Spies and police informers exploited confidences and killed people as a result.

What those rationalising some of Madikizela-Mandela’s associations can’t run away from is that it was the people of Soweto — black people whom she claimed to represent — who ultimately turned against her. They weren’t spies or police informers or government sympathisers. When students at a nearby high school in dispute with the Mandela Football Club burnt down Madikizela-Mandela’s house in 1988, neighbours did nothing to help.

And it was this community who appealed to the Mass Democratic Movement (MDM) — the banned United Democratic Front under another guise — and Cosatu to plead with the ANC to censor her and disband the Mandela Football Club after Stompie and three other young men were kidnapped and tortured at her house for being police informers.

Both the MDM and Cosatu publicly distanced themselves from her. (Part of Madikizela-Mandela’s justification during her trial in 1991 for the kidnappings included a groundless, homophobic accusation against Bishop Paul Verryn, who had sheltered the young men.)

A representative group of activists went to confront Madikizela-Mandela and the football club. At first she refused to give up the young men. Stompie’s decomposed body was later found not far from Madikizela-Mandela’s house.

Curiously, among the MDM activists who went to examine the kidnapped and tortured victims was then trade unionist Cyril Ramaphosa, now the president of South Africa. Understandably, Ramaphosa and other surviving members of that committee have not mentioned any of this in the past few days.

Things did not improve for Madikizela-Mandela after 1990. When Mandela came out of prison, she was thrust into the role of wife — a role that did not suit her.

She went on to work as the head of the ANC’s social welfare department, from which she was fired. In 1991, a court found her guilty of kidnapping in the Stompie case. That six-year sentence was later reduced on appeal to a fine.

After 1994, Mandela made her a government minister, a job from which she was also dismissed over irregularities at her office. In 2003, she was convicted of defrauding members of a funeral fund. This was in effect the end of her political career. (At the time, she was still an MP and president of the ANC’s Women’s League.)

In the early 2000s, she mainly made headlines for clashing with the president, Thabo Mbeki, in public and contradicting the party’s leadership.

Remarkably, she remained popular with rank-and-file ANC members: in 2007, when Jacob Zuma unseated Mbeki as ANC president, Madikizela-Mandela received the most votes for the party’s national executive committee and, two years later, when a general election came around, she was the fifth-highest candidate on the ANC’s list of MPs.

This demonstrated a high degree of reverence and respect among ANC members, perhaps motivated by the real sense that Madikizela-Mandela was persecuted and still represented the kind of uncompromising militancy the ANC leadership was moving away from during this period.

Those protecting her legacy point out that her public showdown with Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1998 — where Tutu demanded she concede that “things had gone horribly wrong” — was politically motivated. After all, this was the period when the unfavorable comparison with Nelson Mandela was in full swing, mainly because she was a loud critic of the unfavorable economic terms of the transition when the mainstream media, business and white people wanted reconciliation rather than redress.

The animosity towards her, some contend, was also rooted in her condemnation of neoliberalism’s negative effects on the poor, state corruption and the open racism in South Africa papered over by rainbowism. (She also, famously, repudiated Mbeki’s HIV and Aids denialism.) They hold that, although she was singled out by the TRC over the events of the late 1980s and her actions periodically equated to that of apartheid’s excesses, no other ANC leaders — or worse, apartheid leaders — were treated in the same way by Tutu.

Mbeki, for example, refused to take responsibility as ANC leader for excesses in the camps. He insisted that the liberation struggle cannot be equated with apartheid’s dirty war.

Still, Madikizela-Mandela’s supporters have been silent about her role in divisive politics in the ANC Women’s League and the corruption allegations she faced when she was a minister — perhaps because too many South Africans are still looking for easy narratives. Good versus bad, this or that.

By the time police murdered striking miners at Marikana and students went on strike over racist symbols and for free education, Madikizela-Mandela was long retired from politics. While she was still alive, it would be the students and Julius Malema’s EFF who would restore Madikizela-Mandela’s political legacy to what it was before 1986. They can’t be blamed.

Two decades in, post-apartheid South Africa had not delivered. Unemployment was at an all-time low, people were vulnerable, and the ANC was consumed by corruption, state capture and leadership struggles. The ANC’s ideological project had run into a cul-de-sac. Madikizela-Mandela’s posture of radicalism, and her rejection by the ANC, seemed very attractive as a political framework. Malema and the EFF derived some of their agitprop tactics (“pay back the money”) and populist flair from her.

The students venerate Madikizela-Mandela as a revolutionary for a number of reasons, in particular because white people didn’t appreciate her or what she went through (some of the student politics is defined by race and riling up white people is a part of it) and the new politics, largely shaped on social media, foreground icons. More importantly, Madikizela-Mandela’s critique of the first 20 years of democracy, its limits and the compromises it was constructed on, gelled with that of the students. So did her example in breaking out of the patriarchal constraints of liberation politics.

One important element of the debate about the worth of Madikizela-Mandela’s legacy has been how we deal with our past.

We pick and choose what we want to remember. To return to Nelson Mandela, like Winnie, he is usually separated from the movement that produced him; his better qualities are usually assigned to some obscure source (some moral core or his individual qualities), not to his main collaborators or the movement that produced him.

Locating figures like Mandela or Madikizela-Mandela in history may help to counter the knee-jerk personalisation of politics and our tendency to cast people as cardboard figures, either good or bad and never as complicated.

Politics is reduced to claiming convenient symbolism from the struggle while removing it from its context to justify a current posture, not ideas or programmes.

Madikizela-Mandela’s mid-political life shows the dangers of using personalities for short-term political gratification. To a large extent this is what happened to the ANC under Jacob Zuma, and what may happen to the EFF under Malema. It is also how Ramaphosa’s own embarrassing political history with Marikana is elided as South Africans clamour for a saviour after the long years of winter under Zuma’s ANC.

It is important to defend Madikizela-Mandela’s memory from right-wing caricatures. But, in insisting that we can’t talk about the complexities of South Africa’s liberation history, we are in danger of becoming the people we criticise and in the process sell ourselves short.

Sean Jacobs, originally from Cape Town, is associate professor of international affairs at the New School research university in New York City and is founder and editor of Africa is a Country, a site of media criticism, analysis and news writing