Wealth taxes are in the news after the Davis tax commission reported last week that South Africa is not ready to introduce a wealth tax even though wealth inequality is “extremely high”

Are a significant number of South Africa’s richest people in hiding? You could be forgiven for thinking so, because a wealth report found that there are 43 600 individuals who have net assets worth more than $1-million (R12-million) but South African Revenue Service (Sars) data for 2016 reveal that only 5 627 individuals fell into its top tax bracket.

Global market research group New World Wealth and AfrAsia Bank released their South African Wealth Report for 2018 last week.

Sars’s number for what it calls high net worth individuals (HNWI) includes people who earn more than R3-million a year and people with net assets of more than R16-million. Sars had 37 299 such individuals registered for the 2016-2017 tax year and, according to Sars’ 2017 Tax Statistics report, 5 627 earned more than R5-million a year in 2016 and were in the top tax bracket. This figure does not seem to include all the HNWI provided to the Davis tax committee (see “There are the wealthy — and the very wealthy”).

Most of South Africa’s taxes are on income, not wealth; the South African Wealth Report looks only at wealth.

Income tax (personal income tax, capital gains tax and corporate income tax) makes up 58.2% of all taxes, whereas taxes on wealth — estate duties, donations, securities and transfers — amount to 1.4% of the total.

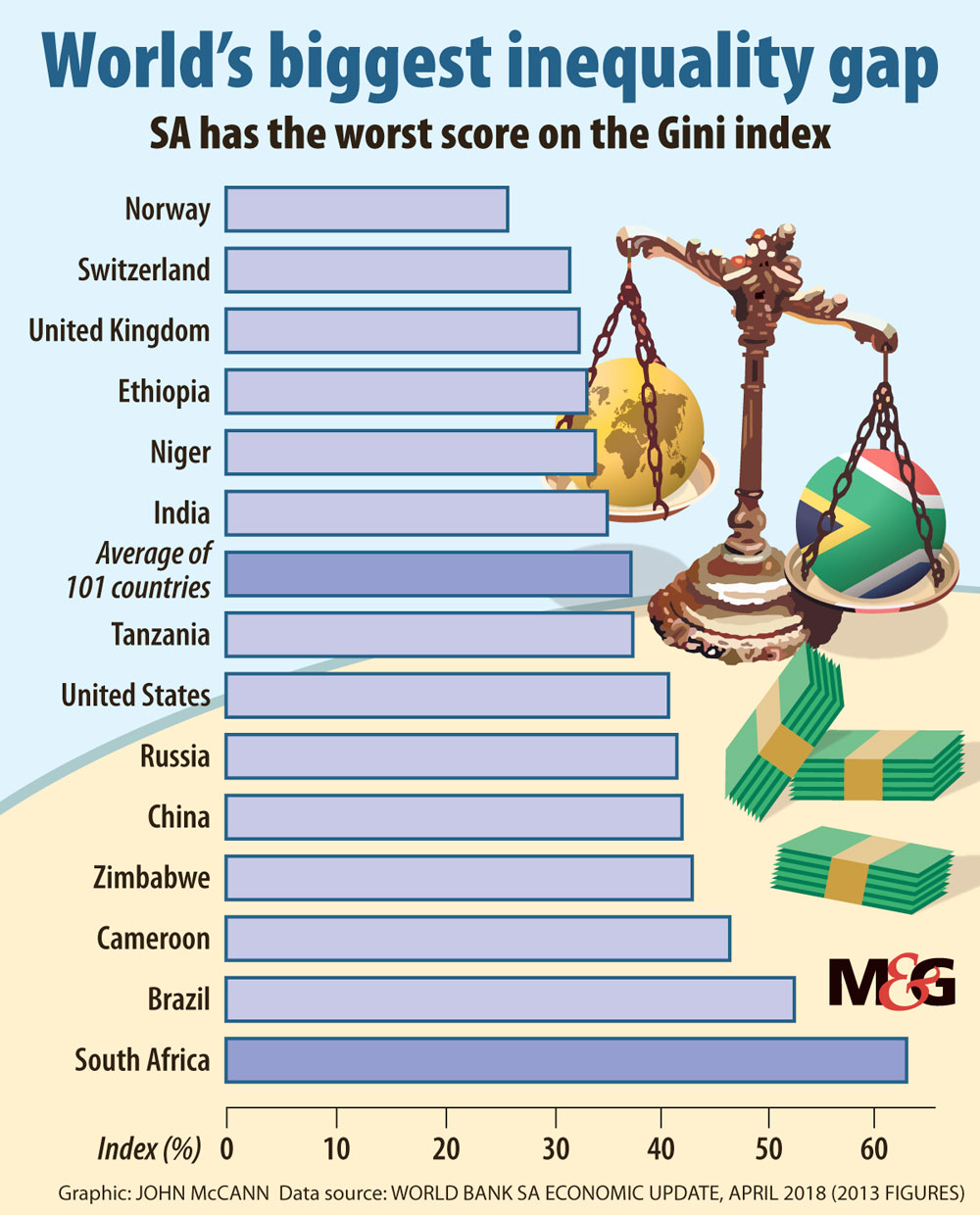

Wealth taxes are in the news after the Davis tax commission reported last week that South Africa is not ready to introduce a wealth tax even though wealth inequality is “extremely high”, with a Gini coefficient above 0.90. This is the measure of income inequality, which ranges from zero to one. Zero would be a perfectly equal society and one represents an extremely unequal society. The Davis report states that the level of wealth inequality in South Africa is so extreme that it renders the middle class “nonexistent” when wealth is used as a measure of living standards.

“The evidence presented on wealth distribution shows the top 10% of the population own more than 90% of total wealth in the country, leaving 80% of the population with virtually no wealth,” says the report.

Davis has recommended that more research be done, to improve the quality of existing data relating to wealth, before the implementation of a wealth tax. This would ensure that the wealth tax system is “well designed and will yield more revenue than it costs to administer”.

His recommendations came as the World Bank released its 2018 South Africa Economic Update, which says South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world. The bank says the gap between the poor and a small emerging middle class and the established middle-class and rich households is widening. But the gap between the established middle class and rich households is narrowing. Race is still a determinant of inequality, but a person’s level of education and employment status are now the primary drivers of inequality.

The bank says policy interventions such as addressing corruption, getting free higher education right, restoring policy certainty in the mining sector and improving the competitiveness of strategic state-owned enterprises could alleviate inequality. In the longer run, the quality of basic education delivered to pupils from poor backgrounds must be improved.

The report says spatial integration also needs to be addressed to bring poor people closer to economic centres where there are jobs; current housing developments are perpetuating the apartheid spatial settlement pattern.

“The various reforms discussed would reinforce each other to generate a larger impact on GDP [gross domestic product] growth, jobs creation and the reduction of poverty,” the bank says. It estimates that the combination of all these interventions would cut the number of poor people to four million from more than 10 million, essentially bringing poverty down by half by 2030.

“In doing so, the country would strengthen its social contract, where the political rights gained with democracy are met with people sharing in the nation’s wealth,” said Paul Noumba Um, the South African World Bank director.

The Davis report also calls for a revision of the Tax Administration Act to make provision for “substantial penalties” should taxpayers fail to disclose their wealth.

The process of gathering more accurate data relating to wealth, so that a wealth tax could be implemented, will start with all taxpayers having to submit a statement of all their assets and liabilities from the 2020 tax year onwards.

“It will provide much-needed information to inform a future decision about a wealth tax and allow Sars and treasury the opportunity to iron out definitional issues with regard to the proposed tax base,” the Davis report says. “Importantly, this information on assets and liabilities will also provide useful information, which Sars can use in verifying declared income under the personal income tax system.”

The Davis report raises the question about the inclusion of retirement funds, which hold R2.2-trillion of South Africa’s wealth. The committee says it could be argued that “any form of wealth taxation will be largely ineffective if the retirement funds are granted complete exemption”.

Given the economic challenges facing South Africa, retirement funds have been granted what have been described as overly generous tax concessions over the years.

In particular, the report questions their exemption from dividends tax since 2012.

The report says taxing retirement funds could have negative implications in the long term but it also recognises that the “retirement funds of South Africa have become relative tax havens for the wealthy”.

In the interim, Davis recommends that the treasury should continue to use existing forms of wealth tax, which it says have significantly underperformed in terms of revenue collection.

In February, then minister of finance Malusi Gigaba announced an increase in the estate duty to 25% on those worth more than R30-million.

Tebogo Tshwane is an Adamela Trust financial reporter at the Mail & Guardian

There are the wealthy – and the very wealthy

The South African Revenue Service (Sars) has 37 299 high-net-worth individuals (HNWI) registered.

Figures from Sars’s HNWI unit for the Davis tax committee’s tax administration report, explains that Sars breaks them down into four subgroups. The majority of the high-net-worth individuals — 20 303 — fall into the “lower affluent” subgroup. They earn more than R3-million a year and have no net asset criteria.

The next subgroup is made up of 10 217 “affluent” people, who either earn more than R5-million a year or have net assets of more than R16-million. In this category, 5 467 people meet only the income criteria and 4 449 meet only the net asset criteria. The remaining 301 people meet both criteria.

The third subgroup are “high-net-worth individuals”, whose income exceeds R7-million a year or have net assets worth more than R40-million. There are 6 545 people in this category, 557 of whom have net assets exceeding R40-million, and 5 824 qualify according to the income criteria. The remaining 164 meet both criteria.

Fewer than 1%, about 234 people, make up the fourth subgroup — the “ultra-high-net-worth individuals”. They have net assets exceeding R75-million. There’s no income criteria for this group. — Tebogo Tshwane