Girls carry bottled water in Maputo

In the township of Chamanculo, in Maputo, Mozambique, a network of household taps made the community water pump obsolete years ago, freeing residents from the daily burden of lugging massive jerrycans of water long distances.

But a water crisis, partly caused by an ongoing drought affecting much of southern Africa, is already reversing progress in this coastal city. An emergency “orange alert”, declared last February by the country’s disaster management council after failed rains, has triggered such strict water rationing across the capital city that the taps are turned off every other day and irrigation is banned.

Unable to afford the private wells, boreholes and extra tanks used by the rich to buffer themselves from the restrictions, Chamanculo’s residents once again find themselves gathering at a single tap.

At 9am, a steady stream of mostly women, some with babies strapped to their backs, line up at Pragosa, a Portuguese construction firm, which is providing free water from a private borehole to the community during the emergency for an hour every day. They fill up 25-litre canisters and carefully balance them on their heads, often making repeat trips home and back again.

Helena Metela, 20, a mother of a three-month-old boy, Ali, says it is a struggle but she has no choice. “The construction company is a little bit far from my home,” she says. “It takes time. Maybe an hour.”

With no end to the current water shortage in sight, the municipality is considering bringing back community pumps to deal with the dwindling supply.

Unlike Cape Town, in neighbouring South Africa where the water supply is at breaking point, Maputo has not got to the stage where officials have predicted a “day zero”, when taps are forecast to run dry. But it is clear that without urgent action, Maputo could be the next southern African city to suffer extreme water shortages. Worse still, future projections are for the city to double in size, from 1.7 million people to 3.5 million by 2035, sending demand for already scant water resources soaring further.

So pressing is the issue that late last month government departments, water utilities, regulators and NGOs gathered in downtown Maputo for a crisis meeting to discuss possible solutions. At the meeting, held jointly by the Mozambique government and WaterAid, official after official warned that the situation was “critical”.

Nobody present was in any doubt of the role climate change is playing in the water shortages. Meteorologists who talked to the Observer reported shifting rainfall patterns, high temperatures and more extreme weather events in recent years. Predictions are that in Maputo and other coastal cities increased pressure on fresh water supply is set to increase.

Jonathan Farr, a senior policy analyst at WaterAid, said climate change was “eating up the world’s water”, while also making it harder to find a solution. “Things that have worked in the past are no longer enough. Climate change makes everything considerably more serious. Cape Town was something you wouldn’t expect to happen. We are now seeing it potentially in Maputo.”

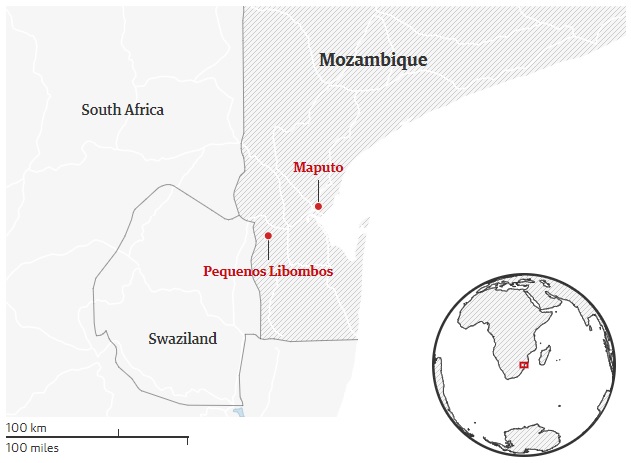

An hour’s drive west from Maputo is the vast Pequenos Libombos dam, which feeds into the Umbeluzi river, the main source of water supply to Greater Maputo. Completed in 1987, the dam has a capacity of 400 million square metres. But in the last two years, the water level has dropped dramatically. Standing on the bridge above the reservoir, Jaime Timba, the dam’s director, points to a series of yellow gauges on the dam’s wall, well above the current water level.

“The water level is too low for the scale,” Timba said “We need to build a new one.” It is only the second time in a decade that the water level has been so depleted. The last time was in 2016, when it fell to 13%. Some water restrictions were enacted then, but they were not sufficient. Meanwhile, everyone prayed for more rain.

In the last four years the Umbeluzi river basin has recorded below average rainfall for the whole basin, while evaporation rates have risen, according to WaterAid. Swathes of land across the region, from South Africa to Zambia, have been hit by high temperatures and low rainfall. Though rainfall in Mozambique has been reasonably good elsewhere, Swaziland in the south-west, whose rivers feed into the Pequenos Libombos dam, has suffered.

Jacinto Laureiro, the mayor of Boane, a town in Greater Maputo, said: “We need to change from thinking about the next 10 years or even 20 years, to thinking long term.”

The current situation, he said, had developed over time, due to population growth, a lack of investment in infrastructure measures to capture water, and because of climate change.

Asked if the situation could deteriorate, he said: “Only God knows.”

Antonieta Ruben, 53, a widow, was sceptical that she would see improvements any time soon.

“I don’t have hope,” said Ruben, who has two sons at university in Maputo and sells chickens to support her family. “This is a normal crisis. They can have promises of getting water but nothing is done.”

This feature was originally published as part of The Guardian’s Global Development project.