Can you guess how many provinces in South Africa have zero radiation oncologists?

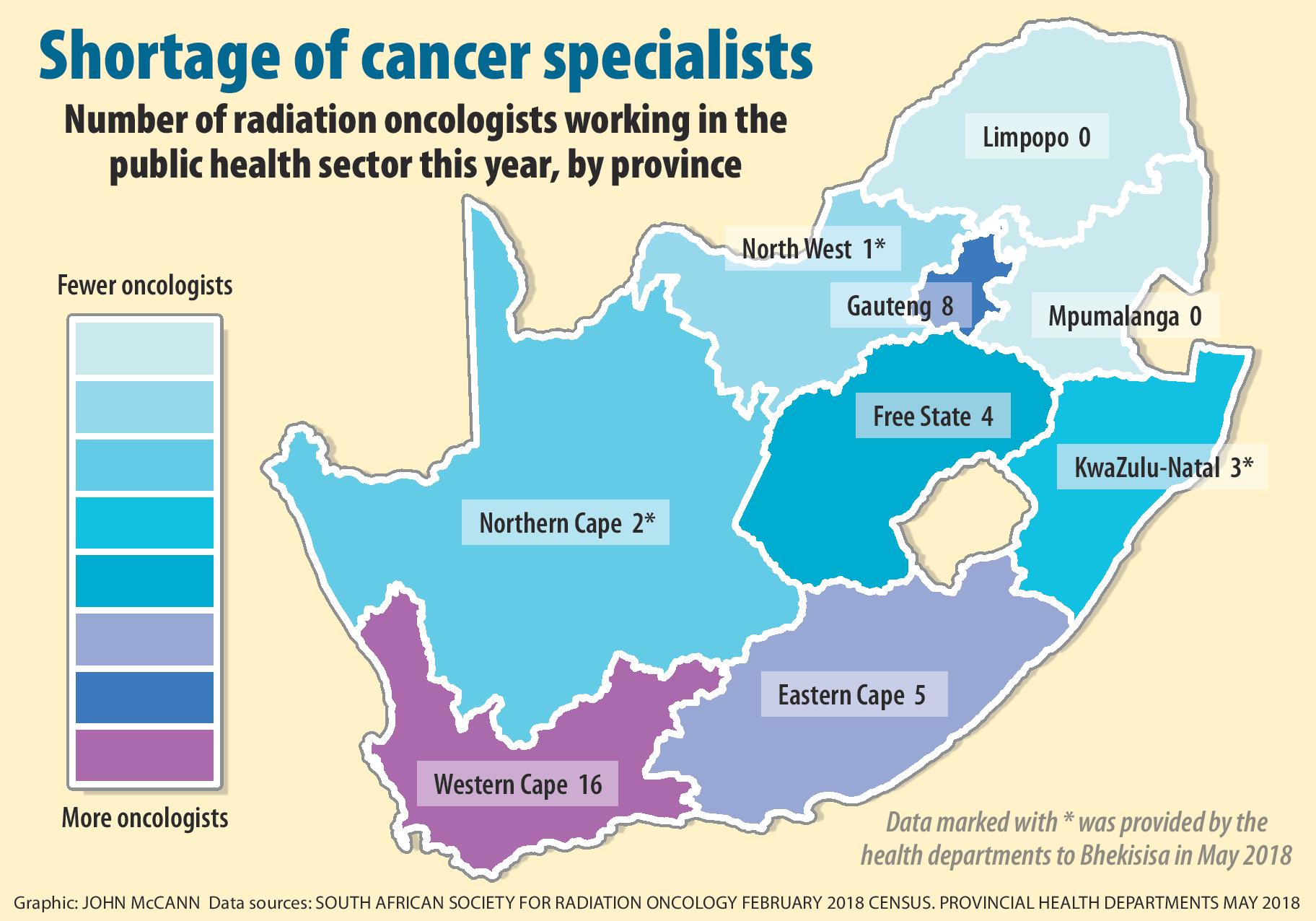

There is not a single radiation oncologist left in Limpopo or Mpumalanga, according to an annual survey conducted by the South African Society of Clinical and Radiation Oncology (Sascro). Half the country’s provinces may be relying on just nine radiation oncologists as cancer services in five provinces buckle — and Johannesburg may no longer be able to pick up the slack.

Only radiation oncologists are qualified to provide the treatment many cancer patients require. This type of treatment is needed in about half of cancer cases, a 2012 study published in the International Journal of Medical Sciences found.

In North West, a lone doctor at Klerksdorp Tshepong Hospital Complex remains as the last radiation oncologist in that province, provincial health spokesperson Tebogo Llekgethwane admits.

In the Northern Cape, the provincial health department says it may have the specialists, but it doesn’t have the machines to provide radiotherapy, which uses high-energy radiation to kill cancer cells.

Radiation can mean the difference between life and death for cancer patients. A study published in International Journal of Medical Sciences in 2007 found breast cancer patients who received radiotherapy after their mastectomies had a 10% better chance of survival over 10 years than those who didn’t.

A typical patient in the Northern Cape will wait four months to be seen in the Free State. Waiting times to start treatment can be even longer.

Mpumalanga and Limpopo are now two of four provinces, alongside North West and KwaZulu-Natal, which refer cancer patients to Gauteng. In most cases these referrals are made through formal arrangements between provinces, health minister Aaron Motsoaledi confirmed in his budget speech on Tuesday.

No such arrangement exists between Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, but at least some patients from the coastal province are paying their own expenses to travel to Gauteng to escape their province’s collapsed cancer services.

“Doctors don’t understand just how little is available in the rural areas. It’s almost impossible to get them treatment,” says Jayne Bezuidenhout, the KwaZulu-Natal representative for the Rural Doctors Association of South Africa.

“You just have to hope your patient doesn’t have cancer.”

The shortage of specialists in KwaZulu-Natal’s teaching hospitals may become a condition in itself as foreign specialists continue to reject the national health department’s job offers, a provincial health department statement shows. Government officials have been quick to blame the private sector’s cushy pay cheques for the mass exodus of public sector doctors.

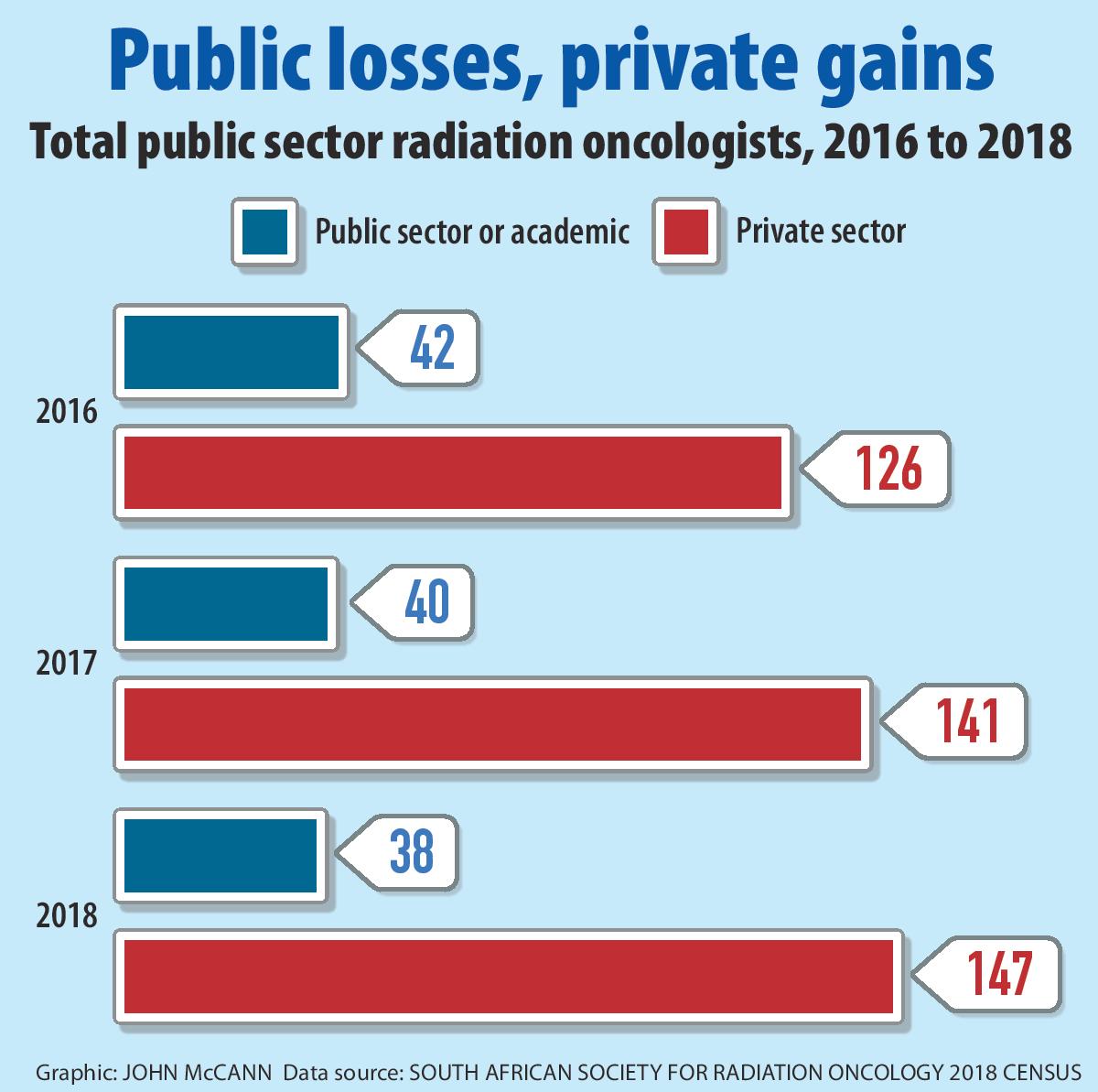

“It’s not about the money,” says Sascro’s Raymond Abratt. “It’s about having a job that is professionally rewarding.” Sascro’s census data reveals an almost 10% decrease in the number of state oncologists since 2016.

For decades, some rural doctors have relied on big, urban centres such as Johannesburg and Cape Town to care for their patients when they couldn’t. Once a beacon of hope, Gauteng may be buckling under the weight of the country’s spiralling cancer crisis.

Only three oncologists — all based at Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital — are left in Johannesburg and five remain in Pretoria, Sascro says.

There are 500 cancer patients waiting for treatment at Charlotte Maxeke Hospital, says chief executive officer Gladys Bogoshi. The hospital is short of three radiation oncology consultants and two full-time specialists.

Nationally, South Africa has just 38 radiation oncologists in the public sector, April data from the association shows. Although the national health department has researched how many such specialists the country would need, this is not publicly available.

At Charlotte Maxeke Hospital, patients report being given appointments into the early evening as the hospital’s few specialists work into the night to try to decrease backlogs. Bogoshi says that two complaints about the quality of care at the hospital have landed up on her desk. Cancer advocates say concerns about the level of care at the hospital have prompted a letter to the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA). The HPCSA was unable to confirm this, however.

In contrast, the Western Cape has 16 cancer specialists, according to a provincial health department statement. Patients wait between two weeks and two months for treatment.

The Free State, Eastern Cape and Limpopo health departments did not respond to Bhekisisa’s repeated requests for comment.

South Africans have a 19% chance of developing cancer before they turn 75, according to 2012 data from the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer. The country diagnoses about 77 000 new patients annually, the agency found.

At his State of the Nation address in February, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced that a national plan to address cancer treatment backlogs and shortages of specialists would be rolled out by mid May. The campaign has not been launched and no details about it have been released publicly.

However, both Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal will receive R100- million to deal with radiation oncology backlogs, Motsoaledi said in his budget speech.

For decades, Gauteng has been the last hope for cancer patients from provinces as far afield as Limpopo. So what happens when Gauteng oncology services buckle?

Cancer services in Durban came to a standstill in June 2017 when the last public-sector oncologist resigned. Provincially, the state now employs only three full-time specialists, who work at Grey’s Hospital in Pietermaritzburg. KwaZulu-Natal patients may now wait as long as a year for their first consultation with an oncologist, according to data presented at a South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) hearing on Monday.

The hearing follows a two-year SAHRC investigation into KwaZulu-Natal’s cancer crisis. Democratic Alliance spokesperson for health in KwaZulu-Natal Imran Keeka says the party has unsuccessfully tried to open a case of culpable homicide against the province’s health department and its embattled MEC Sibongiseni Dhlomo. Public health officials can be held personally liable if prosecutors can prove their negligence caused patient deaths, an article published in the June edition of the South African Medical Journal argues.

For Bezuidenhout’s patients, access to cancer treatment has always been tough.

“This crisis in oncology care is not new; it’s just come to life,” she says.

By July, Durban’s Addington Hospital will have two working cancer treatment machines, according to a provincial health department statement.

Until then, patients will be treated at the city’s Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital, where the Wits Health Consortium, a company owned by the University of the Witwatersrand, will provide oncology services as part of a six-month state contract.

Private healthcare company Joint Medical Holdings will also continue to provide cancer services at Empangeni’s Ngwelezane Hospital until the end of 2019.

But for some, new machines and public-private partnerships will come too late.

About 500 cancer patients have died in KwaZulu-Natal hospitals while waiting for treatment, although this figure is likely to be higher, says Keeka, quoting answers given in the provincial legislature.

“We’ll probably never know how many people this has affected,” he says.

For Bezuidenhout, she knows that treatment may be so unlikely for patients with extremely advanced cancers that she doesn’t refer them to far-off centres for treatment but instead provides palliative care close to home.

She explains: “Patients from rural areas are going to spend a lot of time on a bus to get treatment. They may as well spend that time with their family.”