(John McCann/M&G)

Proposed changes to the Public Audit Act will give the auditor general more power and put a stop to municipalities’ ongoing failure to act, sometimes for years, on audit recommendations.

Auditor general Kimi Makwetu’s latest report on local government audit results revealed the depressing state of governance in towns and cities, exacerbated by what he said was a repeated failure by leaders to act on his office’s “insistent” advice.

Audit outcomes across the board showed a general decline. But his findings were underscored by local government leaders’ failure to act on audit recommendations, such as not investigating findings that flagged irregularities in supply-chain management and indicators of possible fraud or improper conduct.

“Key attention needs to be given to the issues that are continuing to contribute to the lousy audit outcomes,” Makwetu said when he presented his report.

The processing of the Public Audit Amendment Bill is close to completion, according to Vincent Smith, the chairperson of Parliament’s standing committee on the auditor general. The committee approved the amendments earlier this week and the Bill is due to be debated in the National Assembly next Tuesday. If it is adopted, it will go to the president to be signed into law.

The changes will empower the auditor general to refer undesirable audit results to an appropriate body for investigation, such as the Hawks, the South African Police Service and the public protector. The Bill also proposes the power to reclaim money lost to unauthorised, irregular or fruitless and wasteful expenditure from the relevant accounting officers or authorities. According to a draft version of the Bill, if the relevant officials do not recover the money and cannot provide the auditor general with a satisfactory explanation for the failure to collect these funds, they will be served with a certificate of debt that will make them liable in their personal capacity.

The decision to issue a certificate could be taken on court review.

In cases where the debt was deemed criminal the Hawks could be called in to help to recover it, and debt collectors could be called in if it was deemed a civil matter, Smith said.

“The elevation of these issues, through a reporting mechanism of material irregularities, will probably help in the turnaround,” Makwetu said.

Other causes for the lack of accountability included vacancies in key positions. In addition, political infighting in councils and interference in their administration weakened oversight and compromised the implementation of consequences for transgressions, Makwetu found. This environment made local government less attractive for professionals to work in.

Inaction, or inconsistent action, by the leaders created a culture of “no consequences”, and at some municipalities a blatant disregard for controls, including good record-keeping, and compliance with legislation enabled an environment in which it was easy to commit fraud.

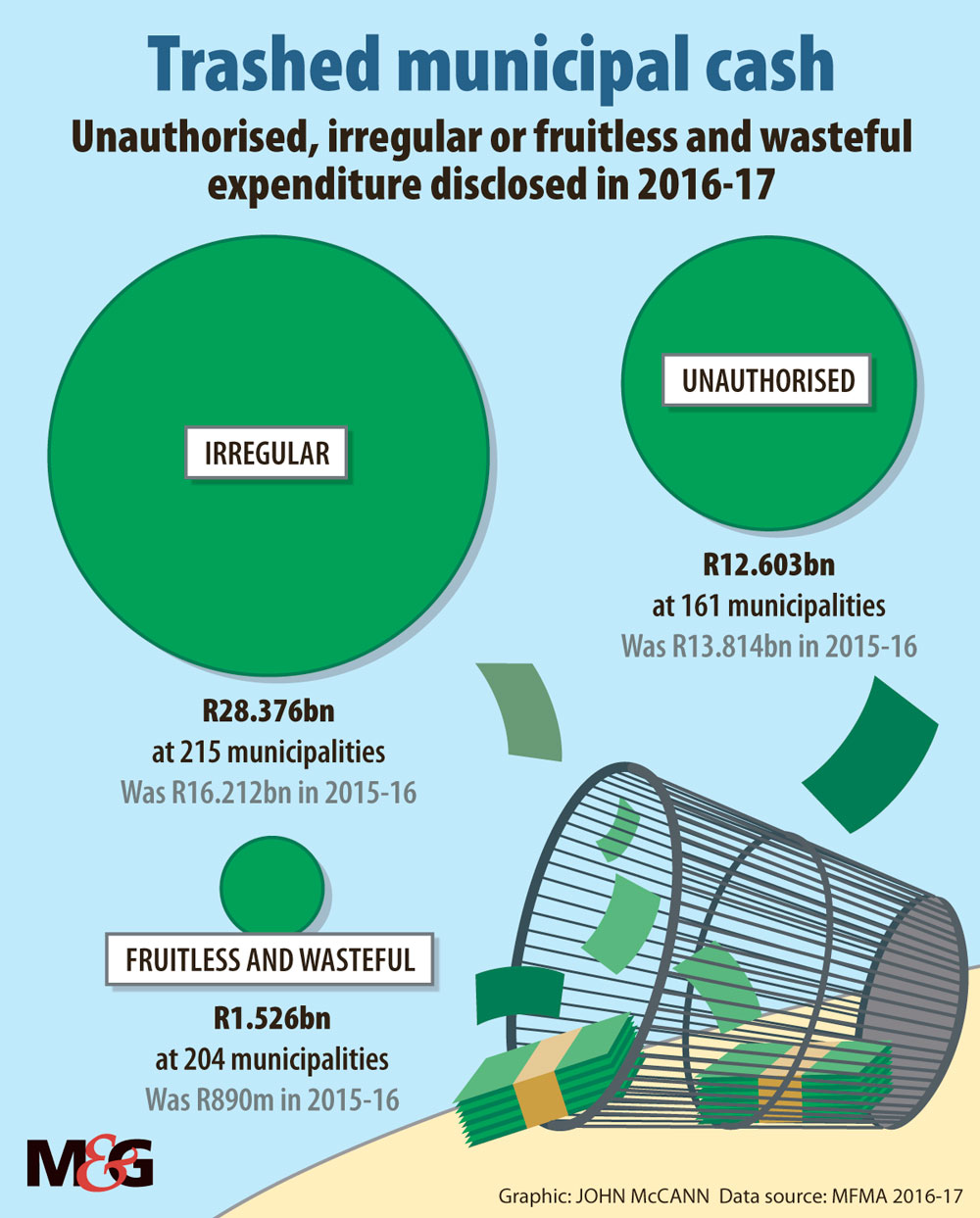

Irregular and fruitless and wasteful expenditure is on the rise. Fruitless and wasteful expenditure for the 2016-2017 financial year rose by 71% from the previous year, from R890-million to more than R1.5-billion. Fruitless and wasteful expenditure is spending that could have been avoided if reasonable care was taken.

Irregular expenditure, which is spending in excess of a budget or not in accordance with budget or grant conditions, rose from R16.2-billion to more than R28.3-billion. But this figure reflected increased efforts by municipalities to identify and transparently report the irregular expenditure, Makwetu said.

About R15-billion of the total amount of irregular expenditure was as a result of spending incurred in previous years but only uncovered and reported in 2016-2017. Unauthorised expenditure declined to R12.6-billion, a 9% decrease from the previous year.

But in all these cases the amounts could be more. For irregular expenditure, 53 municipalities were given qualified audits because information was incomplete.

Makwetu’s office also could not audit procurement processes valued at more than R1.2-billion because of missing or incomplete documentation. Similarly in the case of fruitless and wasteful expenditure, eight municipalities were qualified on the completeness of their disclosures, and 17 municipalities did not make complete disclosures about unauthorised expenditure. Minister of Co-operative and Traditional Affairs Zweli Mkhize said he viewed the regression in audit outcomes with “serious concern”.

The department, in conjunction with the treasury and South African Local Government Association, were working to improve municipal financial management, he said. Measures taken included strengthening municipal oversight structures, such as the municipal public account committees at the 10 municipalities with the largest amounts of misspending; the development of audit action plans for municipalities with adverse audit opinions or disclaimers; and improving compliance with supply-chain management processes by using the central supplier database under treasury’s chief procurement officer.

Makwetu’s findings followed closely on a report from the treasury that had found that roughly half of the country’s municipalities are in financial distress.

The treasury’s latest state of local government finances report for 2016-2017 found that 128 of 257 municipalities were confronting liquidity problems and had failed to deliver services, bill for services and collect revenues due.

As a result, outstanding debtors are “increasing and [these municipalities] are not able to maintain positive cash flows to pay creditors within the 30 days’ time frame as legally prescribed”.

Outstanding debt by households and other customers had “increased uncontrollably” to more than R128-billion, the treasury said. This occurred predominantly in smaller municipalities, which struggled with capacity and governance, institutional and operational inefficiencies, the treasury said.

“At the core of this is that these municipalities do not prepare funded and implementable budgets, despite the allocations and receipt of conditional and unconditional grants,” it said.

In turn, municipalities owe creditors almost R44-billion, notably to Eskom and the water boards.

The treasury added there was an endemic failure to comply with the legislated 30-day payment period as required by the Municipal Finance Management Act and the Public Finance Management Act.

The treasury said there was less accountability at municipalities where the position of municipal manager was vacant or occupied by an acting incumbent. The absence of competent chief financial officers was another concern. According to the treasury’s findings, 40% of municipalities had acting municipal managers and 34% had acting chief financial officers.

In the overall assessment of the health of municipal finances, the treasury found weaknesses in eight primary indicators, such as cash positions, overspending on operational expenditure budgets and underspending on capital budgets.

About 64 municipalities had negative cash balances as of June 30 last year, and the number of municipalities with cash coverage of less than one month had risen from 116 in 2015-2016 to 137 in 2016-2017.