Internet speeds of up to 10 gigabits per second can be reached at South Africa's universities and research institutions.

ANALYSIS

A central player in one of West Africa’s biggest corruption scandals is trying to make his comeback on the London Stock Exchange with a backdoor listing of mining assets in Zimbabwe.

Campaign group Global Witness uncovered the scandal two years ago.

Andrew Groves and his business partner, former England spin bowler Phil Edmonds, were accused of bribingLiberian officials to obtain lucrative mining concessions. In the wake of the Global Witness report, their company, Sable Mining, was forced off the London Stock Exchange’s Alternative Investment Market.

Documents and emails leaked to Global Witness list bribes and questionable payments from Sable Mining to some of Liberia’s most powerful people totalling almost $1‑million.

It was not an isolated incident. After Liberia, Edmonds and Groves set their sights on a new prize: the Mount Nimba iron ore deposit in Guinea. To win it, Sable backed the election campaign that brought President Alpha Condé to power. They got close to his son, Alpha Mohammed Condé, paying for gifts and “consultancy services” to advance their business interests and to secure their permits.

In Liberia, the fallout from the report was extensive. Then-president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf ordered an immediate inquiry and then British prime minister David Cameron wrote to her, saying Britain would co-operate to tackle corruption wherever it might occur.

The Liberian task force investigating the allegations filed criminal charges against numerous politicians, including the ruling party’s chairperson and the speaker of Parliament. Groves and Sable Mining were indicted on charges of bribery, criminal facilitation, criminal solicitation, criminal conspiracy and economic sabotage. In London, Sable’s shares collapsed as their investors and advisers pulled out.

Despite all this, Groves denies any wrongdoing.

Revival bid

Now Groves is making his comeback. Sable Mining, renamed Consolidated Growth Holdings (CGH), is moving rapidly towards relisting its mining assets in Zimbabwe in a stock market manoeuvre known as a “reverse takeover”.

Within a month of President Emmerson Mnangagwa coming to power, Groves had inked a deal with Contango Holdings Plc, a cash shell floated on the London Stock Exchange only weeks earlier, according to a public announcement from the stock exchange.

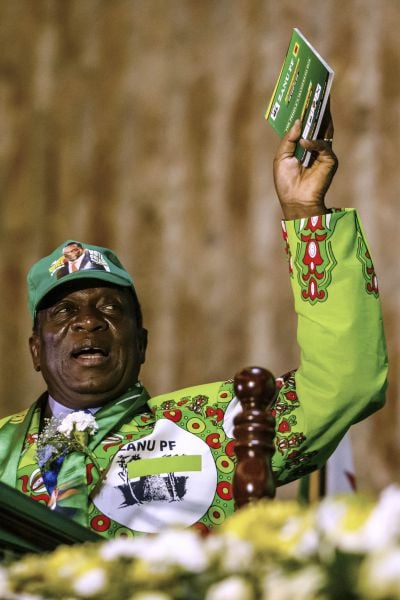

[Soon after Emmerson Mnangagwa became president Andrew Groves made his move to relist CGH (aka Sable Mining)mining assets. (AFP)]

Based on the limited information released by both companies, their plan is this: Contango will buy interests in a coal concession belonging to CGH in the northwest of Zimbabwe. In exchange, CGH will be given shares in Contango and the resulting entity will trade on the London Stock Exchange. It is known as a “back door to the market” because companies can avoid the regulatory scrutiny involved in a traditional initial public offering.

Groves has made a concerted effort to distance himself from his controversial past. Earlier this year, he issued a public statement announcing that all charges against him and Sable Mining had been “irrevocably dropped” after a “comprehensive review by the Liberian authorities”.

This is not true. Groves and Sable Mining were not cleared in a review because there was no review.

Fonati Koffa, who chaired the presidential task force investigating the allegations against Groves and who now heads Liberia’s House of Representatives judiciary committee, said: “This is a blatant and utter lie. There is no comprehensive investigation I am aware of that exonerated these people.

“We remained convinced of their complicity and guilt,” he continued. “I defy Sable Mining or whatever group they have morphed themselves into to produce such a report or the government official who conducted it.”

The reverse takeover is subject to listing approval in Britain. Groves’s misleading statement may be a ploy to clear his name ahead of the planned relisting.

“The UK authorities must now step up to the plate. Both AIM [the stock exchange’s Alternative Investment Market] and the Serious Fraud Office have been fully informed about these cases but are yet to take action,” said Daniel Balint-Kurti, head of investigations at Global Witness.

“The junior market has become a haven for rogue companies and now one of the most notorious of such companies hopes to clamber up on to the main London Stock Exchange.”

A spokesperson for Contango has denied that CGH and Contango have any connection other than the proposed transaction. “The fact that there are common investors/advisers is entirely coincidental,” she said in an email.

Nevertheless, Balint-Kurti says: “The authorities in Britain should pay attention. Edmonds’s and Groves’s bribery scheme was only part of a trail of trickery and intimidation stretching right across Africa, aided by secretive offshore companies.”

The Zimbabwe connection

Contango says that it sees the proposed purchase of a near-term mine from CGH as its entry point into the Zimbabwean market, which is attracting international investor attention since the ousting last year of president Robert Mugabe.

But, like much else, details are thin on the ground.

CGH has an 80% interest in the Lubu coal project through Monaf Investments (Pvt) Ltd and a 49% shareholding in Liberation Mining (Pvt) Ltd, the company that holds the mining licence for the Lubimbi coal project. CGH’s interests are held by its wholly owned subsidiary, Somedon Investments, although the identity of its Zimbabwean shareholders has never been disclosed.

The companies were among the 20 entities awarded special grants by the government in 2010 to explore for coal. But eight years down the line, neither has started commercial operations.

The grant for the Lubu project was due to expire in January. In a report to Parliament last year, the then mines minister threatened to cancel further renewals of the licence because of the company’s nonperformance and failure to develop the project.

Announcing his plans to relist in London, Groves told Bloomberg that CGH’s priority would be coal and its Lubu asset. “I’d like to build it into a mid-tier mining company,” he said.

Contango’s spokesperson has said that Groves is not joining Contango and “he will have no involvement in Contango and/or its Zimbabwe business after the transaction”. She did admit that, as a shareholder, he stands to profit if the company prospers.

Groves also boasted in the interview of his local contacts, adding: “I’ve known Emmerson — the new president Emmerson Mnangagwa — for 15 years.”

This is a history that many members of the new government — including the president — may prefer to bury. One of Edmonds’s and Groves’s most successful companies, Central African Mineral and Exploration Company Plc (Camec), was entangled in a web of corruption, human rights violations and vote-rigging allegedly financed by lucrative mining deals in Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Billy Rautenbach, a major Camec shareholder, was accused by the United Nations of being a proxy for a network of military and political elites, led by Mnangagwa, that plundered the DRC’s mineral resources.

Camec was also accused of advancing a $100‑million unsecured loan to the Mugabe government ahead of the 2008 election. Groves maintains the loan was to pay off external creditors for agricultural supplies, but numerous sources say the money was used to finance Zanu-PF’s brutal crackdown on opposition supporters, during which 200 people were killed and 5 000 were beaten and tortured.

Having promised to revive Zimbabwe’s economy, which has been crippled by severe currency shortages, Mnangagwa is under pressure to deliver results. The mining sector has become a key driver in attracting foreign investment. Groves’s self-proclaimed familiarity with Mnangagwa suggests that the president may not be quite the new broom that he likes to claim he is.

But amid the dizzying reports of billion-dollar deals, familiar patterns of unaccountability, vested interests and opaque joint venture agreements are starting to emerge. The return of entrepreneurs such as Groves to the mining sector in Zimbabwe and to the stock market in London will be seen as a serious failure by authorities in both countries to tackle corruption, and brings their commitment to human rights into question.

Global Witness has called on British law enforcement agencies to take action and for the stock exchange to bar Groves and his companies for good. If things really have changed in Mnangagwa’s Zimbabwe, then his government will do the same.