Harm reduction programmes can help injecting drug users reduce their risk of HIV infection.

Hundreds of people in the City of eThekwini could be at risk of contracting HIV and hepatitis as the metro cuts the only prevention programme for drug users.

The city’s health unit has closed the project run by the non-profit TB/ HIV Care Association, claiming that the programme poses a public health risk and breached municipal bylaws.

The closure follows a freak wave in January that caused more than 50 needles and syringes to wash up on Durban beaches. City authorities claim the incident is proof that the programme is unable to collect and dispose of the needles it hands out properly, placing the public at risk.

But almost 70% of the needles the association gives to drug users are returned, the organisation’s data shows.

In contrast, there is no evidence that any of the 5 000 needles distributed to diabetic patients at Durban’s Wentworth Provincial Hospital monthly are returned, according to a 2012 study published in the South African Medical Journal.

The hospital and association are not breaking any rules, the organisation argues.

“If that were the case, any pharmacist who sells a needle or syringe and does not account for its disposal would be breaching the same bylaw,” says the organisation’s spokesperson, Alison Best.

Experts say the city’s accusations are baseless and its decision to close the project has been a crushing blow for drug users – and national efforts to curb new HIV and hepatitis C infections among the group.

People in South Africa who inject drugs are 40% more likely to contract HIV than the general population, primarily because they’re at risk of sharing infected needles, a small, five-city study published in the International Journal of Drug Policy in 2016 found.

Meanwhile, programmes that provide people with clean needles to eliminate the need for dangerous sharing have been shown to cut HIV prevalence rates by almost half in just three years among British drug users, according to a 1995 study published in the journal AIDS.

Injecting drug users are also more at risk of contracting blood-borne virus hepatitis C. A 2005 study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases found between 50% and 90% of injectors in the Untied States were also infected with the disease.

These statistics are why harm reduction programmes – or initiatives such as the one in Durban that seek to reduce the health risks associated with drug use – are also included in the latest national HIV and tuberculosis plan.

The TB/HIV Care Association programme has provided clean needles and HIV testing to more than 1 000 people since it opened its doors in Durban in 2015, the organisation’s data shows.

Within days of the programme’s closure, advocates began hearing harrowing stories from people in the injecting community.

“Three times this weekend I could have been infected with HIV,” one injecting drug user told Shaun Shelly, who is a University of Pretoria researcher in family medicine.

Shelly is also the policy, advocacy and human rights manager for the TB/HIV Care Association.

“When people don’t have clean needles, they’re going to share,” he says. “[Cutting the project] is no more than a political agenda – it’s a violation of rights. I’m disgusted.”

City of eThekwini spokesperson Vuyo Ndlovu is adamant the project is doing more harm than good and that the city had to take action in the interest of its residents.

Needle exchange projects will be part of South Africa’s next national drug strategy, also called the National Drug Master Plan, which is expected to be released this year, Shelly says.

The TB/HIV Care Association has agreements with the provincial and national health departments to provide harm-reduction services, but the City of eThekwini officials argue these deals do not bind it.

“There’s no logic to what the City of eThekwini is doing,” Shelly argues.

KwaZulu-Natal health spokesperson Agiza Hlongwane said the department would not comment on the decision to shut down the association’s project, saying it did not want to be pitted against another government body.

A little more than 600km away, Tshwane has become the first South African city to fund harm-reduction projects for drug users.

The city will devote R1.5-million to provide services such as HIV testing and counselling, needle exchanges and opioid substitution therapy.

Drugs such as heroin – an ingredient in nyaope – belong to a class of drugs called opioids. People who regularly take opioids experience withdrawal symptoms including nausea and muscle cramps within hours of their last dose. The only way to avoid these symptoms is to take more of the drug.

As part of substitution therapy, doctors prescribe legal medicines such as methadone or buprenorphine, to help people avoid withdrawal symptoms but without the high. The medication is often taken under the direct supervision of health workers or pharmacists in the case of Tshwane patients and can help to reduce people’s dependence on illegal drugs.

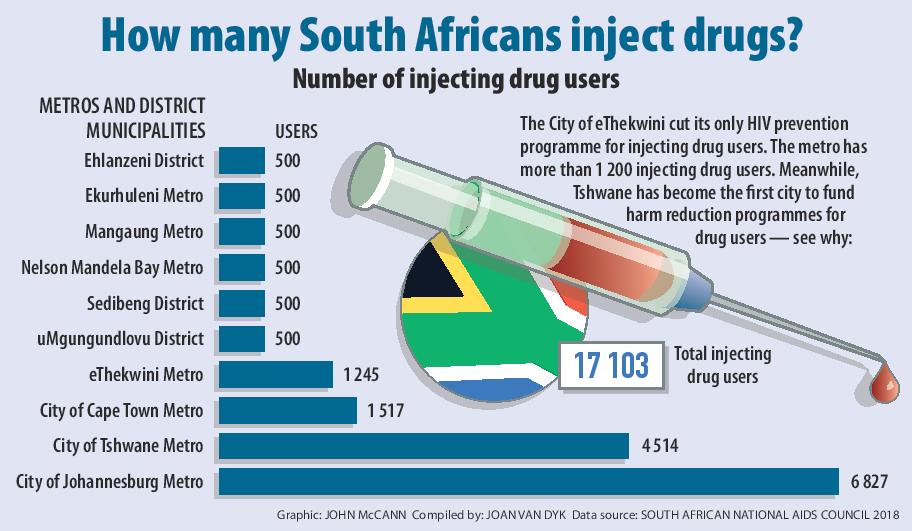

Tshwane has more than 4 500 injecting drug users, the South African National Aids Council’s data shows.

In Durban, TB/HIV Care Association staff say they will do “everything in their power” to get the needle programme running again and have called in legal experts.

“We have the same vision as the city: We want a safe, healthy and caring society. But we need help from the government. The city needs more safe places for drug users to throw away used needles,” TB/HIV Care senior technical advisor Monique Marks told Bhekisisa in April.

“Drug users can’t do this alone.”