Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi will be met with court cases from the private healthcare sector while dealing with pressure from trade unions to speed up the process.

The National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme is coming, whether you like it or not. And so is the end of your medical aid in its present form.

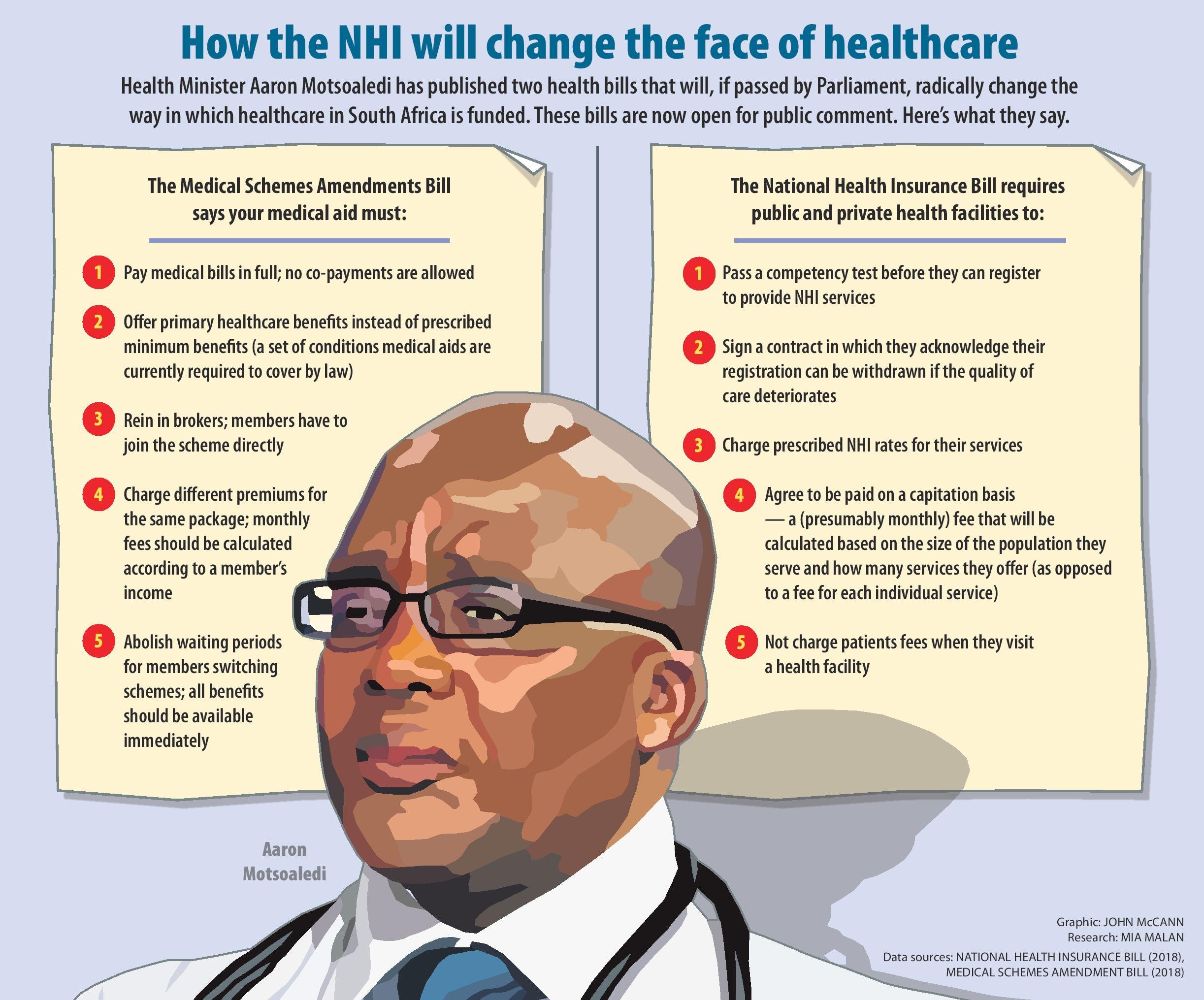

That’s if South Africa’s NHI and Medical Schemes Amendment Bills, which were published last week and are now open for public comment, are passed by Parliament in their current forms.

But the man at the helm of it all, Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi, may face even more strain and uncertainty than those who will be depending on the scheme. He is likely to be met with numerous court cases from the private healthcare sector. And, at the same time, he will face pressure from trade unions to speed up the implementation of NHI. Trade union federation Cosatu has made no secret of its impatience with the minister and called for his resignation earlier this month.

The NHI will be like a huge, statefunded medical scheme that buys health services from public and private health facilities. The idea is to get wealthier people to subsidise poorer people, so that everyone gets access to the same quality of care, regardless of their income.

The scheme is being phased in over two five-year periods and one four-year period, ending in 2026. We’re currently in the second phase (2017-2022), of which one of the main objectives is to put the legislation in place for the NHI to be implemented. For this to happen, 10 pieces of legislation, in addition to the Medical Schemes Act, as well as various provincial health acts, need to change.

The cross-subsidisation between rich and poor will be quite significant: according to the Council for Medical Schemes, the body that regulates schemes, only 16% of South Africans can afford medical aid premiums. The rest of the country relies on a dilapidated public healthcare system, although some of them also visit private doctors, for which they pay cash.

The minister wants the medical aid contributions of the 16% to be used towards the NHI to help to subsidise the cost of care for the other 84% of the population.

The NHI: Two Bills, almost 200 pages may change healthcare forever in SA. Haven’t read them? This one picture will tell you everything.

The NHI will likely be funded by general taxes and possibly payroll deductions. Deductions will in all probability be calculated on the basis of salaries, so that people who earn more pay more.

In the period up to 2026, when the NHI should be fully implemented, the minister wants medical schemes to align themselves with what the NHI will eventually look like: the Medical Schemes Amendment Bill, for instance, requires medical aids to radically change the way in which they bill members. They will no longer be able to charge everyone the same rate for the same package; those who earn more will pay higher premiums.

Medical schemes will also have to scrap copayments; they will have to pay members’ medical bills in full.

Cross-subsidisation will almost certainly change the kind of benefits that schemes offer their members. If medical aids’ ability to raise income through premiums and copayments is reduced, they will have to adjust what they offer.

But if the NHI Bill is passed, the cost of the services will become lower.

Private-sector health professionals who participate in the NHI will be paid in fundamentally different ways: they will only be able to charge prescribed NHI rates for their services. Currently, doctors and dentists practising privately can charge whatever they like, because there are no set fees. For more than a decade the government has tried to impose such rates, but, each time, the private sector has instituted court proceedings and won.

The minister has been instrumental in launching a Competition Commission market inquiry into what he considers exorbitant pricing in the private healthcare sector. But even in this case, the private sector has managed to drag out the announcement of the outcome of the investigation for almost three years. The inquiry was supposed to have concluded in December 2015, but the results are now expected only in July.

Based on the private sector’s past behaviour, the minister can expect court case after court case from organisations representing health professionals for essentially forcing them to charge lower, prescribed rates. Medical schemes will also go to court to fight for their existence. Both groups will be represented by top lawyers and will try to postpone the finalisation of the bills and their content for years to come.

But, even if the bills are passed unchanged, trouble may be brewing — this time from trade unions. In their present state, many state hospitals and clinics won’t qualify to be part of the NHI. Because the NHI will be paying facilities directly for their services, and not through provincial health departments, disqualified facilities are likely to run short of funds to pay health workers’ salaries.

The NHI Bill specifies that all facilities that would like to be accredited for the NHI would need to pass an inspection by the Office of Health Standards Compliance, an organisation that monitors the quality of healthcare. The office conducted inspections of about 700 of the country’s almost 4000 government health establishments in 2016/2017. In the Eastern Cape, the province in which the highest number of facilities were inspected, almost all clinics and community healthcare centres were “noncompliant” or “critically noncompliant” with an acceptable standard of healthcare.

Motsoaledi has told Bhekisisa that the competition between public and private facilities to sell their services to the NHI will be “healthy”. But how will unions react when private facilities are co-opted at the expense of government hospitals and clinics, with unionised workers, whose services now won’t be used?

Bhekisisa director and editor, Mia Malan, talks NHI on eNCA’s The Fix.

The Bill also says that health facilities that are unable to “ensure the appropriate number and mix of healthcare professionals to deliver the healthcare services specified in the Government Gazette” won’t be able to obtain NHI accreditation. With critically understaffed government facilities in many provinces, and South Africa’s shortage of doctors and nurses, it’s uncertain where the required number of professionals will be recruited from.

It’s a concern that the Bill doesn’t specify what services will be offered by the NHI and how much the scheme will cost. The minister has repeatedly been asked for a budget, but says it’s impossible to estimate the cost of such a broad service. Estimations have varied from R256-billion a year in the NHI White Paper to private organisations calculating it at R400-billion.

The inequality in access to quality healthcare in South Africa has to be addressed. It’s untenable and inhumane for such a scenario to simply continue. The NHI Bill is most certainly an effort to right numerous wrongs. But is it a workable plan within a public healthcare system that the minister himself has acknowledged is dysfunctional on so many levels? The NHI’s many powerful opponents, and even some who want it to work, say “NO”.

Yet Motsoaledi has warned: “If they [Parliament] don’t pass the [NHI] Act as we are proposing it, you can forget about universal health coverage. [If they don’t] we’ll make noise about the healthcare system in the country every year, but never get it right.”