The heliostat system in KaXu or Stellenbosch

Bandile Siyoko* bought himself a car in 2017, a second-hand Golf 4 GTI in mint condition. It is now back home in Mthatha in the Eastern Cape, where his sister looks after it.

When Siyoko, whose sinewy forearms hide a deceptive strength contained in his slight frame, heard that he and 1 710 others were being retrenched from Evander Gold Mine in February, he decided to part ways with the car, fearing that desperation would drive him to sell it.

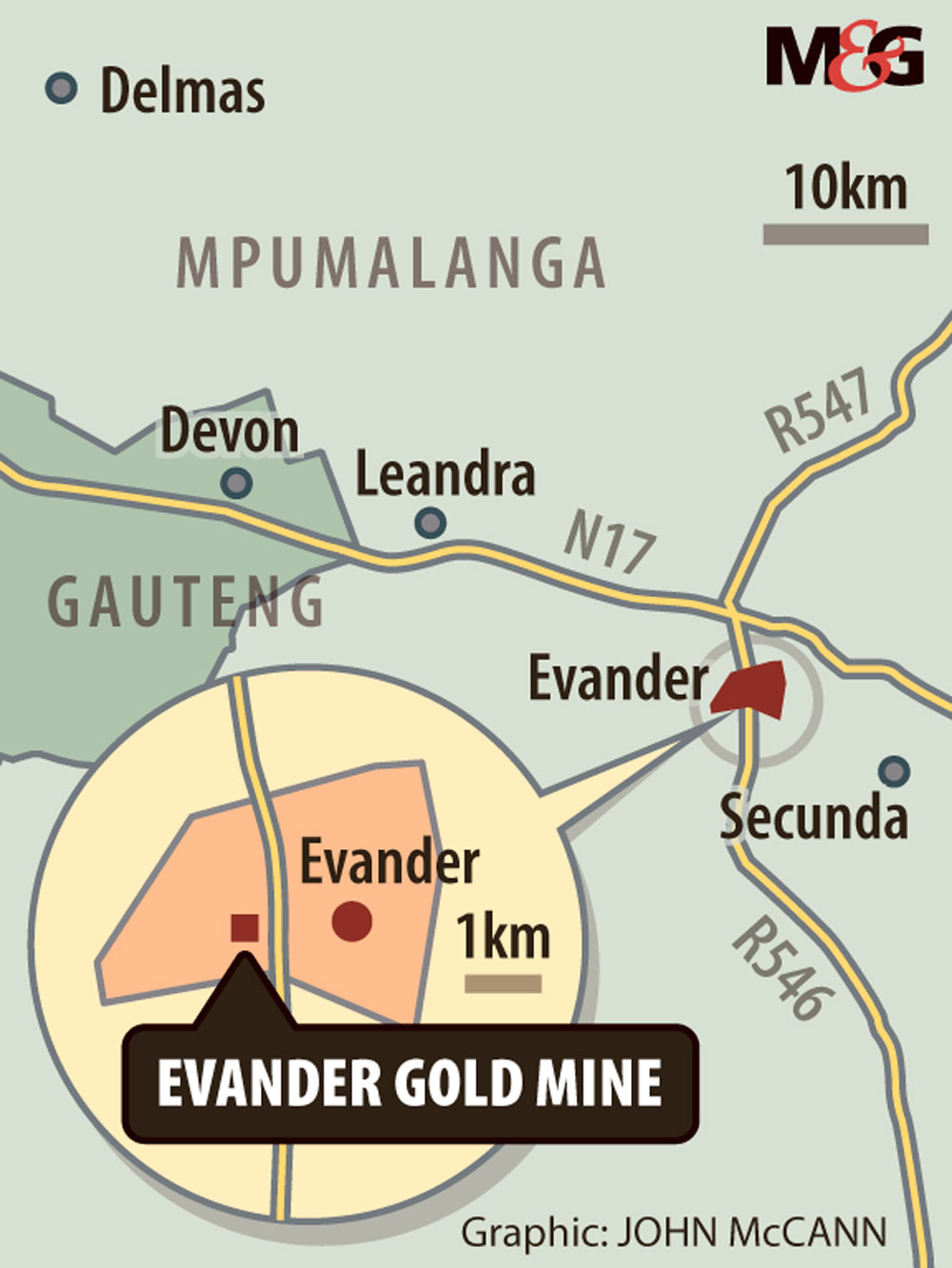

The 35-year-old began work at the ill-fated Evander Gold Mine in Mpumalanga three years ago, after his father had to leave his job at the same mine when he became too ill to work underground. Siyoko doesn’t know exactly what was wrong with his father and simply motions to his chest to indicate the site of the illness.

The mine, owned by Pan African Resources, proposed that he take his father’s place, Siyoko says. But, he adds, he was offered lower pay and fewer benefits than his father, despite the older man having worked at the mine for as long as his son can remember.

The scar that runs from the bottom corner of Siyoko’s right lip to under his chin hardly moves when he talks about this fairly commonplace practice, a relic of the South African mining industry’s colonial history.

Pan African Resources chief executive Cobus Loots told the Mail & Guardian that the company had no choice but to retrench the workers. After reviewing the underground operation of the Evander 8 shaft, the company said in a statement: “There is no realistic prospect of mining on a sustainable and profitable basis in the current weak rand gold price environment.”

The shaft where Siyoko worked was put under care and maintenance at the end of May; 1 710 employees lost their jobs.

Despite some tough months in 2017, the company was still making a profit, according to its unaudited interim results for the second half of that year.

Data from Statistics South Africa shows that 50 000 people lost their jobs in the mining industry just between the first quarter of 2017 and the beginning of 2018. Over the past 10 years, the gold mining industry has shed more than 50 000 jobs.

The average entry-level miner, according to research from the Minerals Council South Africa, has five to 10 dependents. This means that about 4.5-million people depend on the shrinking industry.

“The whole community relies on the mines … Really, people and their families are just devastated,” said community leader Thabiso Mofokeng of the mass retrenchments that have been implemented at Evander.

Siyoko has two daughters, aged eight and four years old. They live with their maternal grandparents and Siyoko’s sisters in the Eastern Cape; he sends R3 000 each month.

Bandile Siyoko took his father’s place working at the mine when his father became too ill to work. Siyoko was one of the workers retrenched, but does not want return to work at the mine under a labour broker because the pay is lower and the hours longer. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

A few metres from him, his colleague Sylvia Macu* is leaning on the terrace railing outside the local Kentucky Fried Chicken. She tightly holds an envelope that contains the two certificates the mine gave her when she was retrenched.

Macu worked at the mine for a year. The 36-year-old has to make a living to support her four children, and her husband’s seven other children. In total, she supports 14 dependents split between Embalenhle township in Mpumalanga, where she lives, and the Eastern Cape.

The township, like most of Evander, is teeming with mostly men milling about in faded overalls marked with the logos of the surrounding mines. A school bus, emblazoned with the familiar Sasol emblem, struggles through the township’s narrow streets. The company owns five coal mines in the area.

To get from the city centre to Embalenhle, it is best to cut through to the mine on a road lined with triumphant-looking palm trees. Towards the road’s end is a deserted spaza shop, the letters of its name “Amandla” crumbling at the edges.

In May, Pan African Resources announced it was “reviewing the merits of mining the Evander 8 Shaft pillar [an area of rock left untouched around the shaft to ensure its integrity], which may extend the final closure date of the shaft, and assist with further employment opportunities”.

Despite the promise of the review, the company went ahead with the retrenchment process — resolving to keep only 100 maintenance workers.

After being handed their exit papers, retrenched workers were given the opportunity to sign up to work under a labour-broking company tasked with mining the Evander 8 Shaft pillar. The name of this company cannot be verified.

Uncertain future: Workers wait outside the Evander Gold Mine near Secunda, Mpumalanga, where miore than 1 700 workers were retrenched in May. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

In the last week of May, hawkers were selling vegetables in the area outside the mine, as a throng of workers hung around, waiting for their exit papers.

One mineworker who spoke to the M&G on said condition of anonymity — as he leaned against the wall of the human resources office — that he is sceptical about potentially working under the labour broker, but is calmed by the prospect of still having a job.

Loots told the M&G it is likely that a labour broker would only be brought in after at least six months. “If we can bring in a contractor, 300 to 400 people will work for two or three years … But we don’t know yet.”

One month later, on a sunny Highveld winter’s day, only one hawker remains. A white bus transporting a handful of helmeted passengers passes the entrance of the mine and stops in front of her stall.

No security guard stands in front of the rusted revolving doors. But there are still workers going in and out. Some of them are contractors working underground in 12-hour shifts. A former permanent employee refuses to say how much he is paid, but confirms that his salary and working conditions have changed.

The legality of replacing a permanent workforce with labour-broker workers after embarking on a retrenchment process is contested.

Retrenchments must be based on the employees’ conduct or capacity or on the employer’s “operational requirements”. According to the Labour Relations Act, “operational requirements” are based on the economic, technological, structural or similar needs of an employer.

Employing others to do the same work generally indicates that there was no “operational requirement”, labour lawyer Suzanna Harvey told the M&G.

Reynaud Daniels, also a labour lawyer, said: “Often, the use of labour brokers to replace existing workers will be considered unfair, but not always.”

Carin Runciman, senior researcher at the Centre for Social Change at the University of Johannesburg, said that bringing in a labour broker might allow the company to pay its workforce less, as the company does not pay for benefits such as pension funds.

“Companies [prefer to] avoid to get in front of the CCMA for unfair dismissal[s]. This is a loophole employers use,” Runciman added.

Siyoko, a member of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), said he believes the trade union was not on their side during the retrenchment process.

The NUM is one of the main trade unions at Evander and signed off on the mine’s retrenchment agreement.

Siyoko said NUM had no mandate from the workers to go ahead with any agreement.

“One day, they [the union representatives] just came and told us that an agreement had been signed.”

NUM Highveld regional secretary Tshilidzi Mathavha denied this.

The retrenchment agreement signed between Evander Gold Mines and the NUM stipulates if there is still work to be done in the mine after the retrenchment, the company would use retrenched workers and if “said work is to be done by a contractor, the said contractor will use the services of the retrenched employees”.

Siyoko did not register for potential work under the labour broker because of the longer hours and lower pay. As a permanent worker, he said, he worked eight to nine hours a day, which had changed under the labour-broker regime. Contracted workers are allegedly expected to work in 12-hour shifts.

Siyoko’s 25-year-old colleague Xola Mquqo* also said that he would not return to work under the labour broker. Before coming to work at Evander, he had worked as a labour broker worker at a nearby coal mine. He took home only R2 500 a month. Working at Evander, he had earned more than double that, he says.

Both men hope to find work at Sasol. In the meantime they will attend the training that Pan African Resources promised to provide workers in the retrenchment agreement.

Standing in the doorway of his small room in Embalenhle, squinting his eyes through the smoke of his recently lit cigarette, Mquqo called the retrenchment a “big loss”.

“Now I have fokkol,” he said. — Additional reporting by Oupa Nkosi

*(not their real names)

Reskilling is often inadequate

In an SMS seen by the Mail & Guardian, the retrenched Evander Gold Mine workers were told to report to Gert Sibande TVET College in Evander for their 10-day courses on Monday, June 26.

Bandile Siyoko has been assigned to attend training for welding, whereas Sylvia Macu will attend a tiling course. Xola Mquqo is still waiting for the SMS.

The Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act requires every company that applies for a mining licence to present a social and labour plan that outlines its plan to contribute towards the socioeconomic development of the areas where they operate.

Section 46 of the Act says the plan must present “mechanisms to save jobs and avoid job losses and a decline in employment” and “mechanisms to provide alternative solutions and procedures for creating job security where job losses cannot be avoided”. This includes a reskilling programme.

Joseph Mantisetse, the National Union of Mineworkers’ newly elected president, criticised the quality of the training often provided by mining companies.

“To be effective, a reskilling process should last one year at least, for miners to have full knowledge and understanding of a job,” he said.

Christopher Rutledge, mining and natural resources manager at Actionaid South Africa, told the M&G there is nothing in the law that describes how companies are expected to undertake the reskilling process. This is agreed upon during the negotiations between the trade unions and the management.

“If the workers’ union is weak, often there is no reskilling process,” Rutledge said. — Amélie Soirant and Sarah Smit