Mammoth task: Born to Kwaito may at times read as if it was created on the fly

BORN TO KWAITO by Esinako Ndabeni and Sihle Mthembu (Blackbird Books)

Writing engagingly about music when one has not studied music theory or played an instrument is among the hardest things to do in journalism. In this and other incarnations of the craft, one must avoid clichés masquerading as descriptors and hackneyed attempts to convey nostalgia. Paying homage to context is sacrosanct yet many of us writing today were hardly born or were not of age at the advent of kwaito. The challenge then becomes: How do we fully enter the music, and by so doing, how do we take the reader along with us?

Reading Esinako Ndabeni and Sihle Mthembu’s collective debut Born to Kwaito, these questions and many others entered my thoughts. They came from a place of admiration and empathy. Early on in the book, Mthembu describes the feeling of being somewhat paralysed by the expectation of putting out a book but flourishing when it comes to delivering other journalistic assignments.

Granted, the thought of having a body of work dissected for its coherence and completeness is more daunting than producing piecemeal portions of writing that can be propelled to great heights by the singularity of the topic and the access of the writer to his subjects.

Because Mthembu is plagued by the idea of being a pretender, he decides to hit the tarmac: “It became obvious to me that to isolate myself was not the way to write about kwaito. That in order to have words on the page, I would need to spend less time at my computer trying to get water from a stone, and go out into the world.” So one December, he substitutes the humidity of Durban days for the crispness of Johannesburg nights, and Born to Kwaito begins in earnest.

As a fellow journalist once said to me, our core duties are not the production or the study of music, so we tend to write around the subject, teasing out its social meaning rather than attempting to critique its merits head on. Born to Kwaito is one such book, driven by the almost oppositional approaches of its co-scribes.

Ndabeni works out a feminist lens through which to critique the genre retrospectively, while Mthembu mostly uses interviews interspersed with childhood memories as a way of connecting us to some of the genre’s main architects. The key tension in this book — which is never quite resolved —lies in these divergent approaches.

In the first two chapters, Ndabeni discusses two pivotal points that have often come up in the framing of kwaito as a cultural phenomenon: its political merit and its relation to hip-hop. She concludes that its political spirit lies in its embodiment of joy (fighting for the right to party, as it were) and that it should not be seen through the prism of hip-hop.

Ndabeni’s theoretical approach, peppered at times by long-winded sentences, is important in so far as it balances Mthembu’s more journalistic approach. It also throws up interesting gems about how the cultures have been analysed. We come into contact with interesting, if bizarre ideas.

For instance, Ndabeni introduces us to African-American author Yvonne Bynoe, who claims that “while rap music can be globalised, hip-hop [as a culture] has not been and cannot be”. Ndabeni then states that at some point, she did see local hip-hop as communicating a disconnect with its local identity but has come to be more open to the world as a place of cultural exchange.

While Ndabeni’s framing is useful in broadening our understanding of kwaito in its relation to other forms of music and South Africa’s political climate, I am unsure of its place at the beginning of the book. One almost pines for the personalities, as opposed to Ndabeni’s subjectivity. Mthembu’s line about going out into the world is, after one has read the entire book, an inadvertent comment on his colleague’s approach.

A reason that Ndabeni’s other chapters, such as Plagued by Hypermasculinity seem to work better is partly because of sequencing. The segue from being immersed in the creative approach of Mapaputsi, a veritable live wire, and then delving into a reappraisal of Dr Mageu’s Model C is that the previous chapter (Mapaputsi Makes it Darker) brings us onto street level. Even as we critique a street artform through a somewhat academic tone, Mthembu has succeeded in making Mapaputsi a complex figure and, by extension, his peers.

When Ndabeni’s chapter shifts, and segues into Arthur Mafokate’s string of totalitarian relationships, it sets the track up for a neat baton handover to Mthembu who goes in on the concept of Mafokate as kwaito’s most hideous man.

Reading this section of the book in the week Mafokate was being removed by the board of the Southern African Music Rights Organisation in light of “the serious assault accusations levelled against him”, one got that spine-tingling feeling one gets when a cultural artefact taps into the national zeitgeist.

Ndabeni’s resolutely feminist stance, and Mthembu’s unflinching approach when it comes to unmasking the evil that men can and will do, combine magically in this three-chapter sequence. Arguably, this is upended by the decision to include a chapter titled “Kwaito Women”, as if the contributions of women to this culture bear concision. One could harp on about the pitfalls of this approach but there isn’t too much of a need, because Ndabeni’s chapter is quite compelling. Moreover, women feature to some degree, in the Yizo Yizo and Durban chapters.

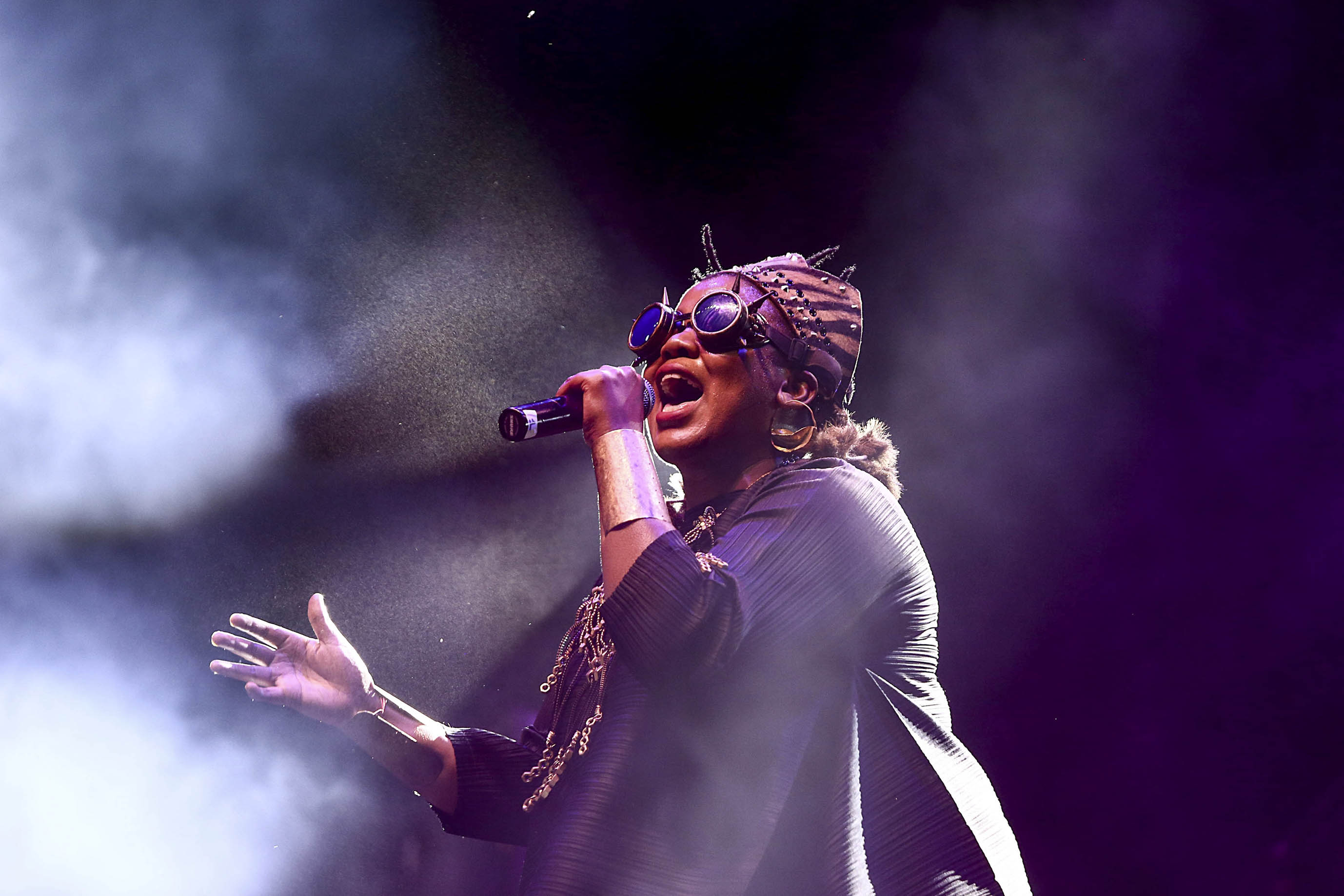

In Kwaito Women, Ndabeni grapples with “the imposition of my feminism” as she tries to locate women in kwaito. She struggles with the easy trope of sexualising Lebo Mathosa and can’t fathom how Brenda Fassie’s family owns next to nothing of the singer’s estate. She writes of Thandiswa Mazwai’s pioneering, independent presence in the scene and is upset by DJ Tira promising to rein in Zodwa Wabantu’s language after a strongly worded onstage comment about owning her body.

[Thandiswa Mazwai is cited as one of the pioneers of the kwaito scene by co-author Esinako Ndabeni. Photo: Thuli Dlamini/Gallo Images/The Times]

Other standout chapters in the book include the Yizo Yizo chapter, buoyed by Mthembu’s obvious love and deep commitment to television and film, as well as the Durban Future, Past and Present chapter, because of the obvious gifts proximity to the subject yield for the narrator.

Ndabeni’s “Looking Back Into the Future” was also quite enjoyable in that there are flashes of hitting the tarmac, thus imbuing a different sense of intimacy into her writing.

As for the entire book, Born to Kwaito is both thrilling and infuriating. Thrilling because one sees two young writers unafraid to take on a mammoth task in South African cultural history: rethinking kwaito. It is infuriating because one sees the hallmarks of speed and the demands of other careers at work here too (the gift and curse of being young and gifted).

A sentence in Producer’s Paradise seems to sum up the dilemma. Musing about Robbie Malinga after the producer’s death, Mthembu writes: “If I’d known this would be Robbie Malinga’s last interview, I’d have asked better questions.” This, to me, says that Born to Kwaito should have been labelled “Volume I”, because it is a snapshot and not definitive — not that it pretends to be. It reads like a book created on the fly, thus demanding more instalments. The ages of the writers, most especially Ndabeni who is barely out her teens, means we can be sure more is to come. I, for one, am waiting with bated breath.