Magnus Malan was probably the second-most powerful person in South Africa at the time. (Leon Botha/Beeld)

NEWS ANALYSIS

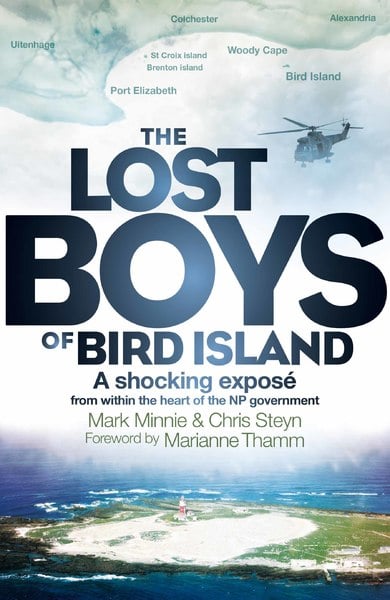

In an extraordinary echo of events described in the just-released book The Lost Boys of Bird Island, co-author Mark Minnie was reportedly found dead on Monday this past week in Port Elizabeth.

It is not clear yet whether Minnie’s death is seen to be a suicide, but the book details two apparent suicides in the course of an investigation Minnie conducted into paedophilia among highly placed politicians in the late 1980s — suicides that, in the analysis of the book, begin to look much like planned assassinations then set up to look like suicide.

There were reports soon after his death that a suicide note had been found, but also that the gun retrieved from the scene at a smallholding on the outskirts of Port Elizabeth was not Minnie’s. His co-author, Chris Steyn, told News24 that she and Minnie had received threatening phone calls in the weeks before his death. Publishers Tafelberg said that Minnie was following up new leads in the story of alleged abuse of male youths on Bird Island that he and Steyn told in the book.

“He was excited about the publication of the book and the disclosure of allegations which, according to him, had been covered up for 30 years,” said Tafelberg. “He said that the book was ‘only the beginning’.”

An inquest will take place.

Minnie was the policeman who first uncovered evidence that Cabinet ministers in the apartheid National Party government were involved in the sexual abuse of under-age boys.

The boys were taken to Bird Island, off the east coast of South Africa, near Port Elizabeth, to spend time with Cabinet ministers who, according to information in the book, were flown to the island by military helicopter.

The book tells how the case was ultimately shut down by intervention from high up in the PW Botha government. Minnie left the police and has worked for the past twenty years as a teacher in the Far East. He returned to South Africa for the launch of the book, and Steyn is reported to have said they were dealing with new evidence that had emerged.

As Minnie tells the story, which he felt he was unable to let go of despite having left the police, he had followed up the case of one of the youths, who was secretly hospitalised and treated after being shot in the anus while at Bird Island. This led him to one of the people involved, and two apparent suicides followed soon after. The victims, however, were untraceable, and it would have been hard for Minnie to make a case, even if the file had not been taken from him in its entirety by a senior police officer. He was taken off the case and later left the police.

As Minnie tells the story, which he felt he was unable to let go of despite having left the police, he had followed up the case of one of the youths, who was secretly hospitalised and treated after being shot in the anus while at Bird Island. This led him to one of the people involved, and two apparent suicides followed soon after. The victims, however, were untraceable, and it would have been hard for Minnie to make a case, even if the file had not been taken from him in its entirety by a senior police officer. He was taken off the case and later left the police.

The book ends with an appeal for any victims still alive to come forward, and shortly after publication one did. Netwerk 24 reported: “He told the publication that he had been kidnapped at the age of 13 in 1987 by a group of white men in Port Elizabeth.” He was “raped and forced to perform other sexual acts by former defence minister Magnus Malan and another ‘uncle’”.

One of the ministers was John Wiley, minister of environmental affairs in the PW Botha government. Wiley was found dead, apparently by his own hand, in March 1987, weeks after the apparent suicide of Dave Allen, a conservationist who had a guano concession on Bird Island and who was close to Wylie. Minnie had confronted Allen with the accusations, and he allegedly confessed.

The book implicates other Cabinet ministers. The use of a military helicopter points to another alleged visitor to the island, Magnus Malan, the minister of defence in the PW Botha government and probably the second-most powerful person in South Africa at the time. He was known for his highly militaristic response to any opposition to the apartheid regime. According to the book, on at least two occasions Malan was confronted with the Bird Island allegations; he responded differently on each occasion, either denying or deflecting the claims.

A third minister alleged to have been involved is not named in the book, for legal reasons: he is still alive and could sue for defamation, say the publishers. Barend du Plessis, who was the minister of finance in the PW Botha government, told Rapport on August 12 that the references to the “third minister” were clearly aimed at him and that he strongly denied any involvement.

The story of the abused youths of Bird Island was investigated by several publications at the time, but definitive evidence was not forthcoming and the victims could not be traced. The few articles that were published drew the ire of prominent National Party politicians.

Gavin Evans, formerly a reporter at the Weekly Mail, recounted how reporters at The Star were advised to steer clear of the Wylie case, and Martin Welz’s investigations for Rapport were quashed: “The entire cabinet came down on the editor, and the story was killed.”

The Lost Boys of Bird Island is published by Tafelberg