Lift-off: Nursultan Nazarbayev celebrates winning the national presidential elections in Kazakhstan in 2005. Election monitors said the polls were marred by widespread intimidation by the police and security forces. (Mikhail Voskresenskiy/Sputnik)

COMMENT

Africa has a reputation for particularly poor quality and controversial elections. I have just come back from Zimbabwe, where the election campaign was heated and the outcome explosive.

When delays in the counting of the presidential ballot led to concerns that the elections were being rigged in favour of President Emmerson Mnangagwa, frustrated opposition supporters took to the streets to protest. In the resulting clashes with the security forces, at least six people lost their lives. Whatever one thinks about who actually won the election, this was clearly not the “new start” that the Zanu-PF government was hoping for.

The frequency of these kinds of events has led to considerable pessimism about the prospects for free and fair elections. Every few years, the continent seems to have a major election crisis: Madagascar (2001), Kenya (2007), Zimbabwe (2008), Côte d’Ivoire (2010), Gambia (2016). It was therefore unsurprising that the BBC responded to yet another disputed election in Kenya in 2017 by holding a debate on whether democracy is working for Africa.

Even some of the elections that are generally considered to have gone well actually suffered significant limitations — we just tend to overlook these because there is consensus that the right side won.

For example, the transfer of power in Zambia in 1991 did not occur because of a high-quality election. Instead, the opposition won because so many people wanted to see the back of Kenneth Kaunda’s government that the unfair advantages enjoyed by the ruling party were not enough to keep him in power.

A similar story can be told about the South African election of 1994. The polls were rightly celebrated because they brought Nelson Mandela and the ANC to power, but there were significant problems in terms of biased media coverage, the failure to print sufficient ballot papers, long delays and even with the process of counting the vote. Had the election been close, these matters could have led to a serious political crisis.

Given all this, it is easy to be defeatist about the prospects for democratic consolidation. But when elections on the continent are compared with those in other regions, it turns out that African elections are not as bad as many people think.

Good and bad

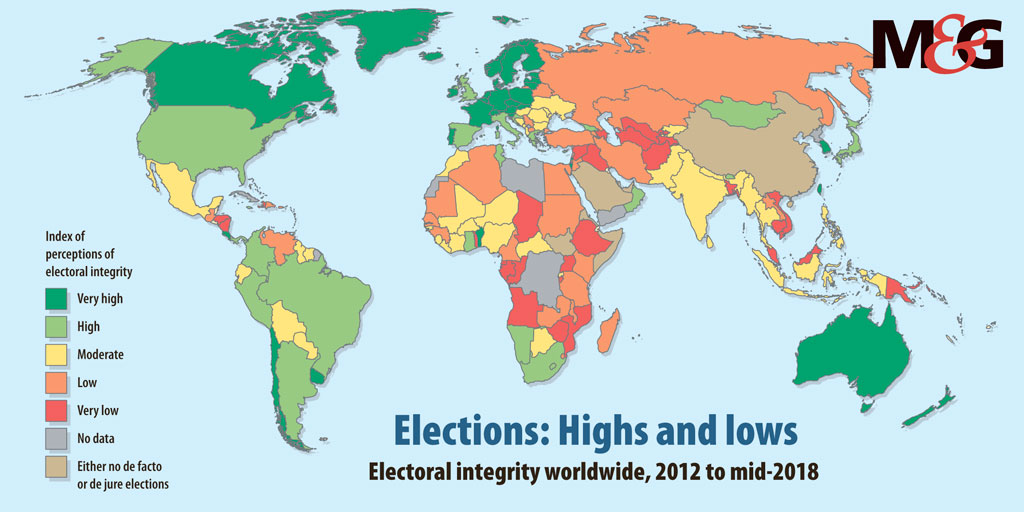

In my new book, How to Rig an Election, we compared the quality of elections around the world over the past 20 years. This is possible because the Electoral Integrity Project has helpfully rated every election out of 10 based on the reports of election observers. Although this means that their measure is subject to the same limitations as observation reports, it makes it possible to get a sense of where elections are better and where they are worse.

On average, sub-Saharan African elections scored pretty badly — just 4.9 out of 10. Of course, this overall figure merges very different elections in very different countries — it includes both high-quality polls in Ghana and Mauritius and low-quality contests in Chad and Uganda. Although it masks a lot of variation, it is also clear that this figure reflects the popular imagination about the low quality of African elections — especially when it is compared with the average of 7.3 in Latin America and 8.9 in Western Europe.

What was more surprising was that we also found that, in similar new democracies around the world, Africa is not exceptional. During the same time period, the average quality of elections was lower in post-Soviet Europe (4.6) and Asia (4.8), and only a little higher in the Middle East (5.4). Indeed, some of the elections in these countries were considerably more problematic.

Elections in Kazakhstan demonstrate just how problematic other elections can be. Before presidential polls scheduled for December 4 2005, one of President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s main critics, Zamanbek Nurkadilov, the mayor of Almaty, was found dead. He had been shot twice in the chest and once in the head. The official investigation branded his death a suicide. Opposition leaders wondered how a man could shoot himself three times in two different places and declared his death a political assassination.

Against this background of political violence, human rights groups and election monitors identified a series of other abuses, including assaults on opposition supporters, censorship, the destruction of campaign material, and widespread intimidation by the police and security forces. Unsurprisingly, Nazarbayev recorded a landslide victory, with 91% of the vote.

The case of Kazakhstan — and others like it — demonstrate that the assumption that African elections are exceptionally bad is simply not true. Instead, they turn out to be on a par with many other countries that reintroduced multiparty politics at about the same time.

Dirty tricks

One of the things that struck us as we worked our way through the figures was that, although the average quality of elections in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and post-Soviet Europe is pretty similar, the ways in which elections were manipulated are not. Governments have a number of strategies that they can use to give themselves an unfair advantage in elections, which we call the dictator’s toolbox. These include gerrymandering, vote buying, playing divide and rule with the opposition, repression, fake news and ballot box stuffing.

The combination of rigging strategies that a leader uses is shaped by the resources they have, how desperate they are and the pressure placed on them by the international community. When we surveyed the tactics that authoritarian leaders in Africa use to make sure they remain in power, we found that they were often less brutal than the tactics deployed in other regions.

This pattern is easiest to see if we focus on two common forms of manipulation — repression and vote buying. Just over a third (37%) of African elections feature state targeting of the opposition with violence, intimidation and harassment. Although this is lamentable, it is lower than in Asia (39%), the Middle East (38%) and post-Soviet Europe (47%).

Instead, African leaders seem to rely on other strategies, such as vote buying, which is reported to be a significant problem in two-thirds of elections — over 20% more than in any other world region. Vote buying undermines accountability and encourages political corruption. But in countries with the secret ballot, it has been shown to be a less effective strategy precisely because citizens can “eat with the government and vote with their conscience”.

Changing landscape

The fact that African elections are not exceptional is important because it demonstrates that there is nothing “African” about poor-quality polls with controversial outcomes. We have no reason to believe that there is something distinctive about African societies, or African political systems, that means they are less compatible with democracy than the rest of the world.

In others ways, this is not a good-news story. What our book demonstrates is that the average quality of elections around the world is much lower that most people realise. Compromised elections are not rare — in many parts of the world they have become the norm. That African elections are no worse than those in Asia, the Middle East and post-Soviet Europe will be of no comfort to the opposition parties that are regularly cheated out of power, and it is clear that the continent deserves much better.

But there are also reasons to be more positive. The average quality of elections may be low but elections in a number of states, including Cape Verde, Ghana, Mauritius and South Africa, are now of a consistently high quality.

At the same time, the tendency of leaders to rely on vote buying to a greater extent than outright repression means that opposition parties have a better chance of making a breakthrough, as we saw in Nigeria in 2015, Gambia in 2016 and Sierra Leone this year.

Partly as a result of these two trends, the number of countries that have experienced a transfer of power on the continent has increased from only a handful in the early 1990s to 20 today.

This is significant because it means that, although removing a government remains extremely difficult, it is not impossible. Although many opposition parties continue to compete with one hand tied firmly behind their back, Africa is no longer a continent characterised by elections without change.

Nic Cheeseman is professor of democracy at the University of Birmingham