Cool-Ache: I think to some extent you have to be sad to write sad stories

like a general disposition towards gloominess. - Pravasan Pillay. Photo: Rogan Ward

Pravasan Pillay is a literary ascetic. Chatsworth (Dye Hard Press, 2018), his collection of short stories, is largely unencumbered by adjectives and adverbs.

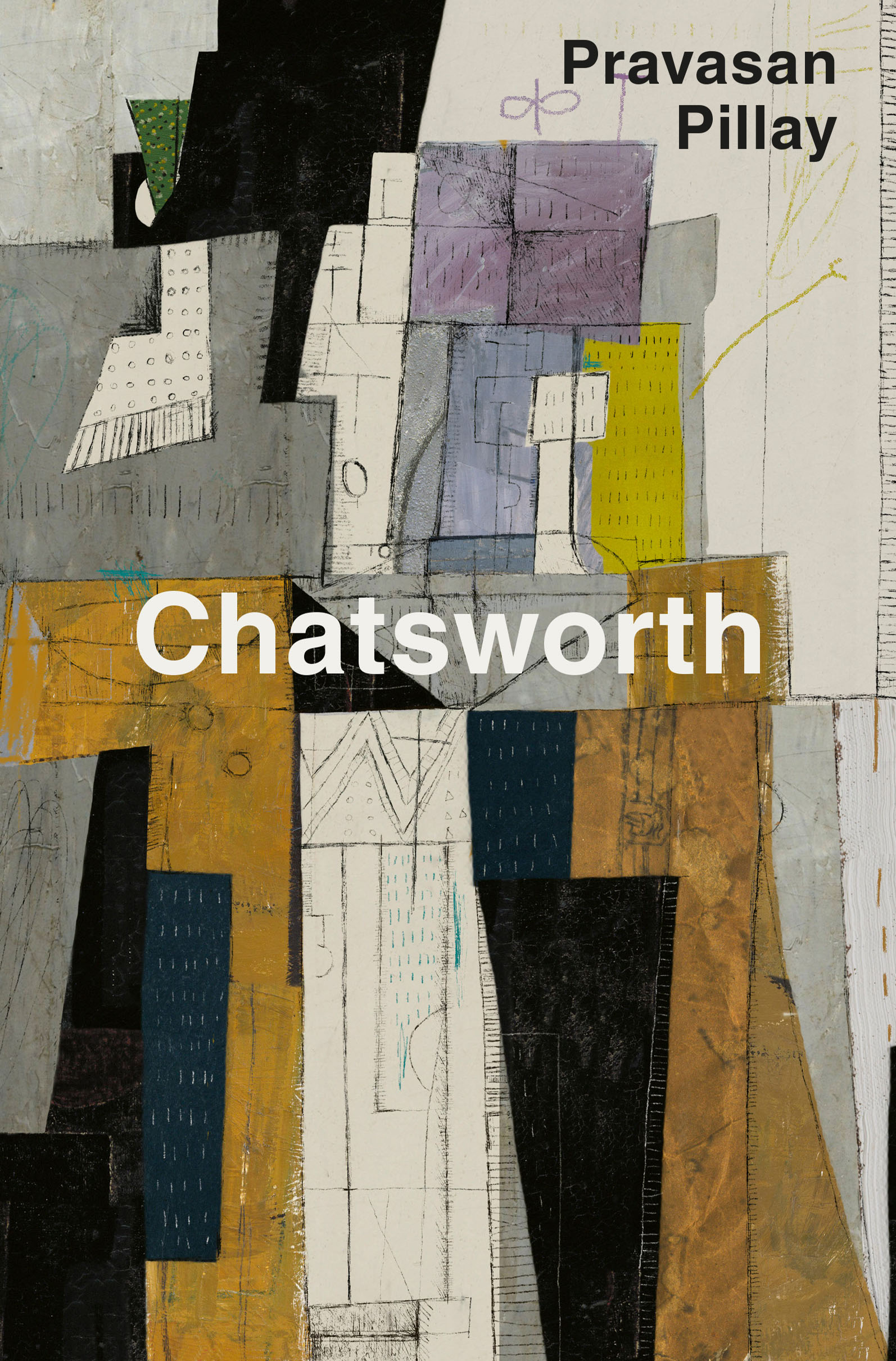

[Chatsworth (Dye Hard Press, 2018)]

His prose is spare yet precise in detail and minutiae. It captures not merely the lives of people living in the eponym of his collection, the former Indians-only township south of Durban, but the claustrophobia and gloom that accompanies class and caste disdain, racial oppression and the fatalism of a dead-end —set to a dead-beat — imposed on individuals and a community.

His stories are the mise en scène of melancholia.

“I have always felt that there is a deep vein of melancholia that runs through Chatsworth and which touches the lives of some of its residents,” says Pillay.

“It’s a place where people were forcibly removed to, from other parts of Durban during apartheid [from 1950 onwards], so there is an obvious sadness in its origins — however, the melancholia I sense is something more, it’s a way of being in the world, it’s a heaviness.”

That existential “heaviness” of Pillay’s characters — most of whom are outsiders — deftly propels his social realist stories, some of which have no discernible plot. Rather, they are layered portraits of people, moods, prejudices and claustrophobias.

In Crooks, there is a single mother illegally selling alcohol from her kitchen who treads a fine line between revulsion, love and duty for her incapacitated, morbidly obese daughter. The Albino is a slow-burning story of a fair-skinned girl — Indian, albino, white, mixed-race? — whose presence in an Indians-only school during apartheid incites gossip among teachers and children, and reaches a tremulous denouement (of sorts) while on an excursion to the Durban Museum.

Pillay, who now lives in Sweden with his wife and son, admits to a “feeling of ‘outsideness’ growing up in Chatsworth” mostly because his family moved around often and he was raised by a single mother.

His parents divorced when he was young, something unheard of in the socially conservative Indian community in the 1980s: “[The divorce] was a definite source of unease and alienation. Unsurprisingly, as I grew up and discovered films, books and comics, I found that I gravitated towards characters on the margins of society. Apart from fiction, I was likewise attracted to human glitches in township life, people who stood out a little from the crowd. But yes, I do feel like an outsider, whether it was while growing up or as an adult in Durban and now as an immigrant in Sweden. I think it’s just the way I am wired and it’s what I gravitate towards when I am writing,” he says of his characters.

“There is a definite sense of claustrophobia in my stories. Many of them take place indoors, in small rooms, without much moving about happening. There is a feeling of ‘stuckness’. In terms of narrative, there is also a focus on the interior lives of the characters — so the claustrophobia is both physical and emotional.

“If you look at the geography of Chatsworth itself, with grid upon grid of tightly packed, semi-detached council houses and shared walls, with people basically living on top of each other, then you can easily see that this claustrophobia is built into the bones of the township’s architecture. There’s no way to avoid it in fiction.

“But this claustrophobia, this closing in on all sides, needn’t be seen as a negative thing. I certainly don’t see it as negative anyway. It’s this close physical proximity to each other that is the basis for the creation of a community bond. Ironically, the book is called Chatsworth, which hints at some kind of macro-view but the book is really all about interiors.”

Growing up in Chatsworth, Pillay collected touch-me-not plants and made mixtapes for girls.

He rebelled by reading widely — from comic books and the encyclopaedia sets bought from door-to-door salesmen, which were ubiquitous in working-class Indian homes, to the instructions on the back of packaged food —listening to alternative music and writing zines and plays.

“I felt like I was different but at the same time there was a sense of shame because ‘How dare you think that you are different?’. It was only when I went to university at the former University of Durban-Westville in 1996 that I got more connected with other writers and mixed with people from other backgrounds. These people saved my life,” he says.

After university, Pillay worked as a journalist and as an event programmer at the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Centre for Creative Arts, which organises the Time of the Writer and Poetry Africa festivals, among others.

During that time he founded a micro-press, Tearoom Books, and went on to publish two chapbooks of poetry, Glumlazi (2009) and 30 Poems (2015). He also co-wrote a collection of comedic short stories, Shaggy (2013).

Pillay currently works at a bottle store owned by the Swedish state, which has an alcohol sales monopoly. He has a physically demanding job packing shelves, which he admits to enjoying, but says: “I think about writing every single moment of the day. It’s honestly the only thing I am really serious about.”

It is a seriousness of thought, style, form and the painstaking building of words into sentences and paragraphs which is clear in Chatsworth.

The collection brings together short stories that Pillay has been working on for several years and includes some that have been published in The Con and Prufrock and in collections such as The Obituary Tango: A Selection of Writing from the Caine Prize for African Writing and Urban 3: Collected New South African Short Stories.

Chatsworth also marks a seminal intervention in South Africa’s literary canon because of its sensitive and respectful treatment of South African Indian English — in the manner of Marlon James’s use of Jamaican patois in his Booker prize-winning A Brief History of Seven Killings (2014) and Irvine Welsh’s Scottish working-class dialects in his novels.

Pillay has returned a dignity to a dialect often denigrated for comedic effect by South African mainstream popular culture and has affirmed a people who are not often represented in local literature.

“I wanted to accurately capture in prose the unique and somewhat poetic way in which people speak English in Chatsworth,” says Pillay.

“It’s a variant of English that truly deserves to be documented. Take the sentence, ‘It’s so nice’. A Durban-Indian way to say that would be, ‘So nice it is’. I find this nimble, beautiful and anarchic, like looping or bending the English language inside out and exposing its insides.

“Take also the expression, ‘this thing’. This expression is linguistically interesting because it could refer to both a person or as a synonym for ‘whatchamacallit’. There have been a number of books that do a good job of capturing the slang and expressions of South African Indian English but often the phrasing feels a little off. Theatre is usually better with this because you can instinctively tell when the speech doesn’t ring true. So I wanted to work on getting this phrasing or syntax of South African Indian English right. But it wasn’t a sociolinguistic project — first and foremost I wanted to write stories set in Chatsworth and that meant creating realistic characters and writing realistic dialogue,” he says.

In fastidiously abiding by this social realism, Pillay, who admits that “form keeps me up at night” and is happiest deleting the sentences he likes most, has melded the stylistic character of a young JM Coetzee with the sensitivity to place and a living politics of a Ronnie Govender.

In doing so, he has created a collection of stories imbued with an existential gloom and austere beauty that is simultaneously hyper-local and universal — which cannot be cast into the ghetto of Indianness; the Chatsworth of South African literature.