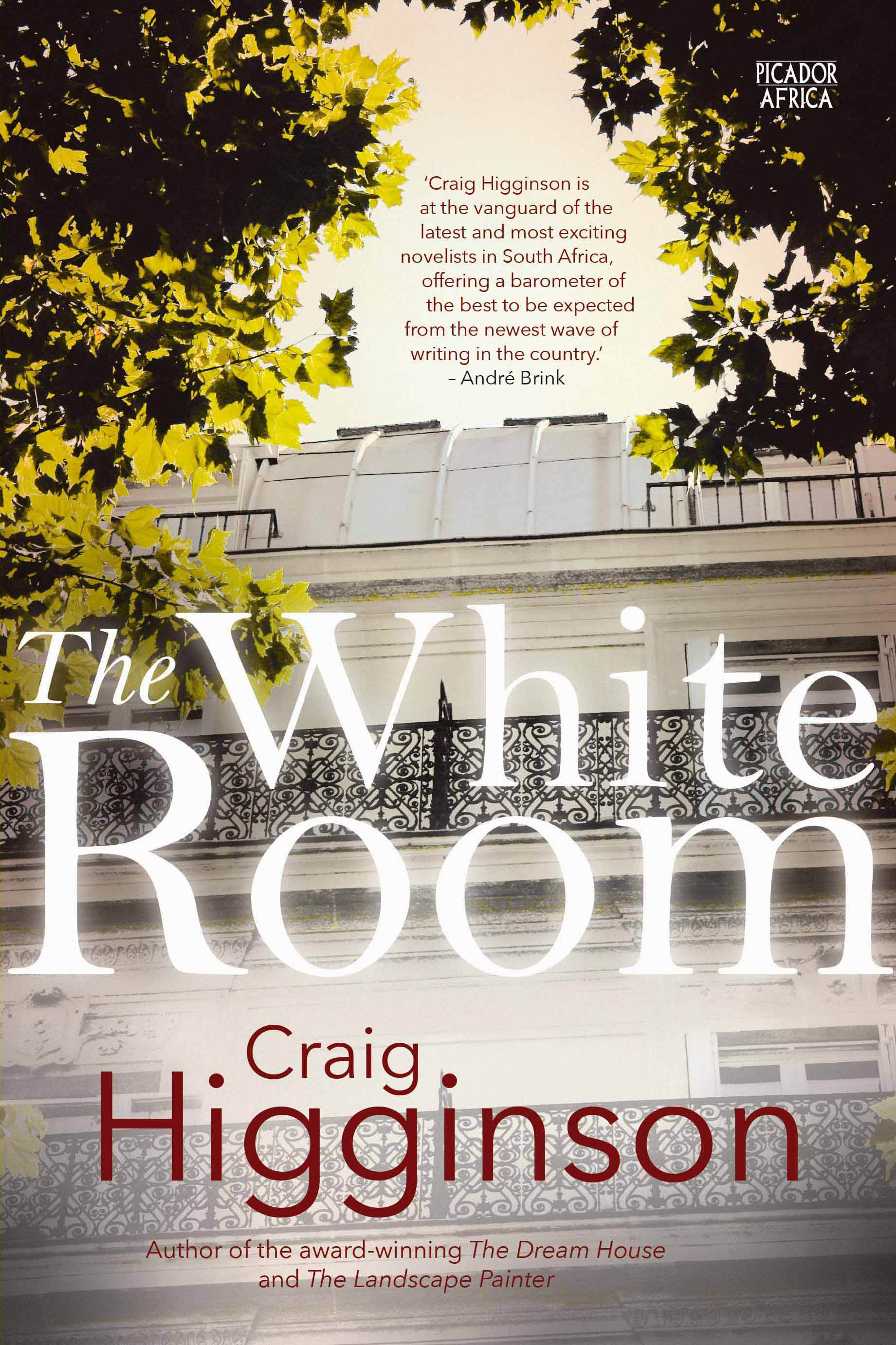

Generations: Craig Higginson drew on his life as a white South African child during apartheid. Photo: Renata Larroyd

“The act of representation is inevitably doomed to failure,” says Craig Higginson, who is seated across from me in a restaurant as we discuss his most recent novel, The White Room. “I don’t think that we could get to represent anything accurately.

“What do we know about the past? We just have memories that are dictated to by our needs for the present. We remember things how we remember them because of what we want to feel right now. We do not have access to the past. Other people we grew up with have completely different memories of the same event.All we can do is create fictions that become metaphors for what is real.”

In The White Room, which is based on Higginson’s play Girl in the Yellow Dress, the two principal characters try to love each other but it seems too much stands between them. Hannah is an English teacher and Pierre is an eager student. They are both drawn to each other by a gnawing need to fulfill their own fetishes.

“Narcissistic in a Freudian sense”, as Higginson puts it, Hannah has her own selfish reasons for giving in to Pierre.

“There are lots of levels of self-abuse and self-harm going on in the novel but hopefully what emerges is the complexity of us, of our relationships and our individual identities,” says Higginson.

Inspired partly by his travels to England and France, Higginson says that after his previous novel, The Dream House, which was a particularly South African tale, he wanted to write a book that was more global in scope. The relationship between Hannah and Pierre (a white South African woman and a man of Congolese descent) can therefore be read as a conversation between Africa and Europe. “Being a white person from Africa, she feels shame around that,” says Higginson. “She realises …that he [Pierre] isn’t of Africa in the way that he pretends. He is but he isn’t.

“Growing up through the Zimbabwean war and apartheid gives us an angle on things, where we can comment on what’s going on in the world in a way that other people can’t,” says Higginson.

“Being a white South African, I can comment on whiteness in way that the average person living in Somerset, London or Paris can’t,” he adds.

A dialogic novel with a play running through the heart of it, much of the novel is spent negotiating who Hannah and Pierre portray themselves to be as they narrow in on each other.

“So they are kind of lying their way towards the truth,” says Higginson. “That state of uncertainty is quite important for me, for the reader to not be sure what is true and not true… When she is trying to tell the truth, he feels it is falsifying him, whereas when she is telling a fiction that digs deeper, he feels seen and recognised.”

Through the milieu of the English lessons, with Pierre still mistaking Hannah for an Englishwoman, ideas of civilisation and the effects of the colonial hangover are teased out. Pierre presents a picture of exoticism to Hannah, pre-empting what she desires from him. Although these issues are nothing new in literature, it is form that assists Higginson towards the realisation of something novel. The White Room is fragmented, presenting as a puzzle or a Rubik’s Cube under construction. We reach the resolution but the path towards it is laced with apparitions and opacity.

Mostly through Hannah, Higginson delves into his own past and childhood. “I couldn’t write an English character with that level of interiority, so I made her South African,” he says. “In a way the novel became about the children of parents who were involved in conflict situations —the Rhodesian war and apartheid South Africa. The Serbian characters, all these became the tonsils that have absorbed the poison of the previous generation and they are trying to conduct relationships but they are fucked up in ways they don’t understand.”

Speaking about the form and the process of writing the book, Higginson says he was aiming for something planned but that was open to surprises. “Too much chaos and it becomes a mess,” he says. “So you need some structures for an internal momentum. With each draft, I tried to have different tasks in mind. I’d have one draft where I was looking at the relationship as a kind of political allegory. In one draft I’d be looking at the psychology of the relationship and then one draft would be childhood and background. So hopefully by the end, I’d have all these different threads running through it but coherent and rich. I mean, you could even read it as a grammar lesson.”

With The White Room, Higginson manages to find an engaging way of writing about the multiple ways colonised societies are bonded to those that colonised them. These are webs we cannot extricate ourselves from but, every now and again, language can be hacked to provide new vantage points.