Wondering: Sol Plaatje's constant travels, during which he communicated his liberal ideas, took their toll on his family and friends.

Sol Plaatje was a man of prodigious talents. He had mastered seven languages before the age of 20 and was a writer of prevailing prose. He was a court translator and newspaper editor. He met and was admired by Lloyd George, the British prime minister, and WEB du Bois, the American scholar and civil rights activist. He would go on to be one of the first African novelists to write in English and was a translator of Shakespeare. But he is best remembered as one of the founders of the forerunner of the ANC, the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), in 1912.

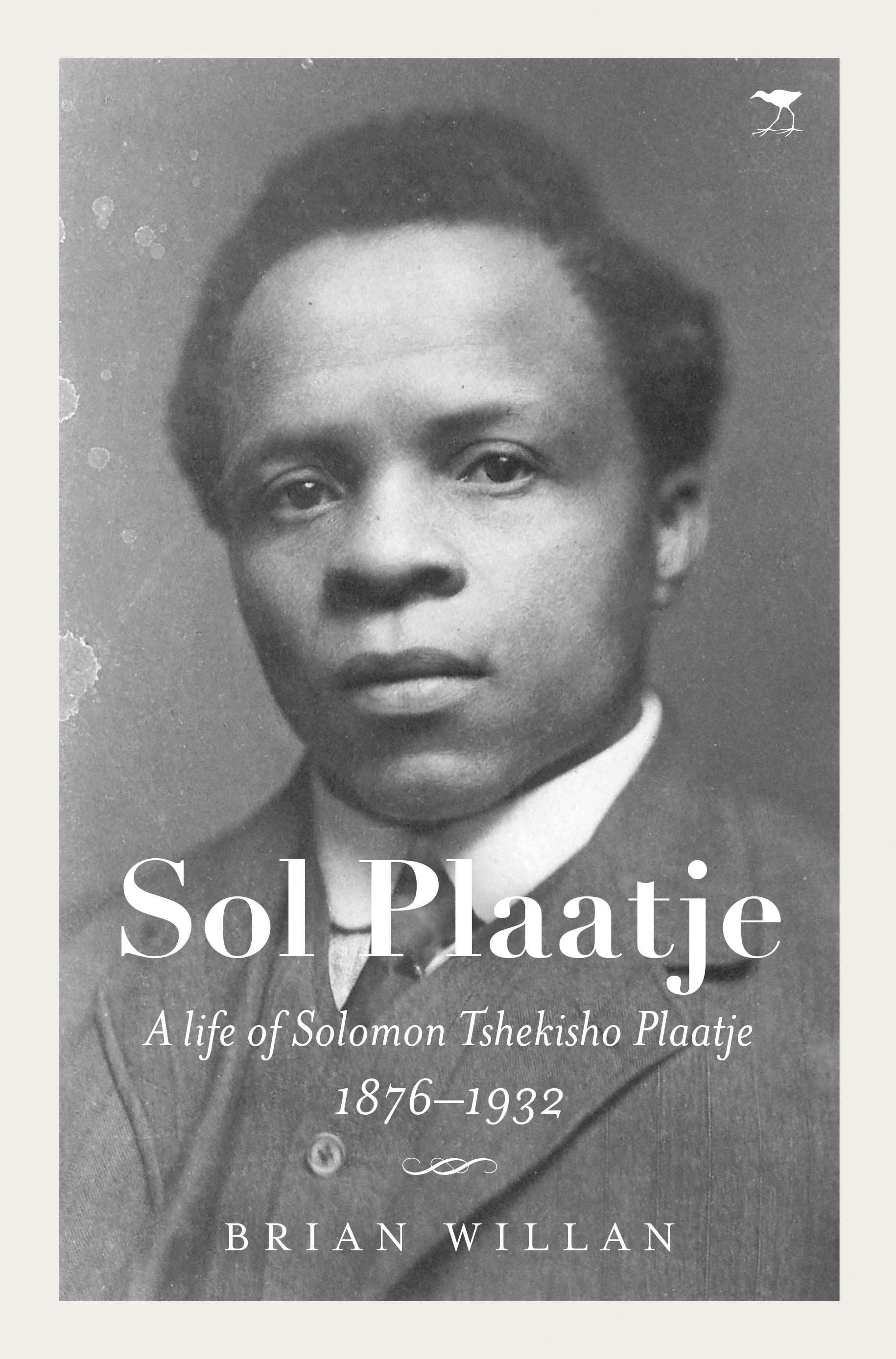

Except for the small biography written by Seetsele Molema, a friend of his family, Plaatje has only ever had one other biographer, Brian Willan. Willan has spent decades researching Plaatje and the biography that has been published under the title Sol Plaatje: A Life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje 1876-1932 is not simply a revision of his 1985 book; it’s an entirely new take.

In it Willan follows Plaatje’s life from his birth into a family of Tswana Christian converts and his education by German missionaries near Kimberley. He traces Plaatje’s life as a court translator, a diarist of the Siege of Mafikeng, a newspaper editor and the first general secretary of the SANNC. He gives accounts of Plaatje’s deputations to Britain, his travels in the United States and the final decade of his life when he published his novel, Mhudi.

The book is a triumph of research to which its length gives testimony.

But to say that Sol Plaatje is simply a biography of one man would be a mistake. It is far more than that. It is a documentation of not only a single life but also the “Cape liberal tradition” with which Plaatje associated. Although the term may have been discredited over the past 60 years of South African politics, Willan suggests that Plaatje was very much a proponent of Cape liberalism. Plaatje, after all, agreed fundamentally with its major tenets: equality before the law and a nonracial franchise. What was more, like the many white liberals who were his friends and political associates, he believed racial segregation was not only impractical in South Africa but morally unconscionable.

Willan’s biography is not a contemporary attempt to revise Plaatje as an early militant. Rather, the work presents Plaatje as a man of remarkable social and persuasive abilities in a time and place that had little interest in these qualities. Historian Tony Judt once said that liberals are the “canaries in the sulfurase mine shaft”. Willan represents Plaatje as just this.

In its pages we see how Plaatje dedicated his life to writing and speaking out against the illiberalism and inequities of the growing race laws in the Union of South Africa.

Perhaps the main feature of the book is just how effective and persuasive Plaatje was in certain circles. Not only did he befriend the white advocate and government minister Henry Burton (who proved a useful ally both in court and in government) but also several members of the British suffragette and Christian brotherhood movements. With their help, he managed to convince large swaths of the British public, including Lloyd George, of the crisis taking place in South Africa. As Willan uncovered, Lloyd George, having been persuaded to meet Plaatje by members of the brotherhood, wrote to the prime minister, Jan Smuts, on two occasions pleading with him to take Plaatje and his organisation seriously. They had, Willan stated, serious grievances and he noted that Plaatje was able to secure “the sympathy of people of power and influence”.

But Plaatje’s problem was twofold. One was the British colonial tradition that supported racial oppression and segregation. The other, as the Cape liberal Sir James Rose Innes put it in a speech in 1929, was that in South Africa “any white moron can vote”. And these white morons were certainly not prepared to listen to or be persuaded by a black man. The tyranny of the white majority, led and facilitated by Barry Hertzog, who also became prime minister, and Smuts was too great a force to be countered by Plaatje’s judicial pleas and testimonies. After coming back from tours of the US and Britain in 1923, he would meet his friend Burton (by then the finance minister) in Tokai, Cape Town, but, as Willan puts it, this friendship was now “distinctly out of place”in the Union of South Africa.

There is another story enmeshed in this narrative —that of Plaatje’s domestic life.Despite his clear love for his family, he was something of a nomad.

He spent many years away in Britain and the US spreading the news of the Natives Land Act (1913) and of the conditions of “native life in South Africa”, which was the title of his most famous political work. In fact, this wandering never quite stopped. Even after returning toSouth Africa he started touring the country for weeks at a time with a mobile cinema.

This, as Willan describes, took its toll on his family. His wife, Elizabeth, and his oldest son, St Leger, would have to shoulder the burden. And it would lead to the cessation of St Leger’s promising academic career.

One gets the sense that at the heart of this was an almost pathological urge to communicate, an urge that was being arrested at each step by the ever-growing racial laws after the union was established.

Mhudi, which was written in English, was in many ways another attempt to communicate to a broader world that would not listen. It would take Plaatje 10 years to find a publisher.

Again, as Willan suggests, at the root of Mhudi was a repository of his liberal political and philosophical thinking. Its feminine lead character and sympathetic representation of certain Boers and Matabeles testifies to this. In his other literary endeavours, he would continue to hold a candle for Shakespeare and the English language in one hand, while shining a lantern on Setswana and its culture with the other.

These culturally diverse sets of interests are delved into by Willan and the research and discoveries he has made in the past decades are of great historic and literary interest. With regard to Setswana, Plaatje went on what might be termed a “cultural struggle”.Once again the gathering forces of the white morons would go some way towards defeating him. However, Willan’s biography has managed to pull out of the divisive ministries of cultural evisceration some of the history of this remarkable man’s work on his own language and its culture.

At the heart of Sol Plaatje are the actions of a man whose beliefs lay in a general honest thought to all. This interest in the common good that Plaatje had (perhaps almost to a fault)was passed down to many other ANC leaders, most notably Nelson Mandela. Just who the current keeper of that flame is in South Africa and indeed the world is unclear. Liberals of Plaatje’s nature are in a state of near extinction.

Willan’s book is, in its field, a masterpiece of writing and research. There are few of these kinds of books around in the world and fewer still in South Africa.

What is more, the subject may well have been forgotten if it wasn’t for Willan’s academic persistence.

Of course, it does have some complicated narratives that are today unpopular. It might not quite reveal the Plaatje some might want to hear about.

It is a history not written simply to please and the accurate and authentic approach to its subject is refreshingly honest.