"With respect to reference to litigation, this means that the IDC has instituted legal action to recover the R37.5-million as well as the R250-million in accrued interest," says Patel. (David Harrison/M&G)

In 2012, the Mail & Guardian sat down with Economic Development Minister Ebrahim Patel in his office at 120 Plein Street, Cape Town, to talk about infrastructure.

The interview delved into government’s drive to shift government spending towards investment, to be spearheaded by the Presidential Infrastructure Co-ordinating Commission (PICC). It would include the development of 18 strategic infrastructure projects that covered energy, water, logistics corridors, municipal development and more.

The state would look to more partnerships with the private sector to improve project delivery, including financing from pension funds to match the long-term investment horizons of these projects. Funding would also come from alternative partners such as the other Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China) nations. The PICC would act as a “clearing-house” for projects to unlock administrative blockages, promising improved efficiency and co-ordination. The state also promised to address administrative prices — such as rising electricity costs — to reduce the burden these were placing on economic activity.

Sounds familiar?

When President Cyril Ramaphosa announced the government’s fiscal stimulus package last Friday, which is underpinned by a major infrastructure drive, the echoes of past promises were eerie.

But Patel told the M&G this week that things will be different this time, not least because of strong political backing and the strengthening of the PICC.

“The PICC structures work best when underpinned by strong and consistent political support. The announcement by the president provides the necessary backing to it,” Patel said.

From the 2016-2017 period, investment in public infrastructure began to decline, Patel said, despite significant growth up until then. The fall was partly driven by slower spending by state-owned entities (SOEs), thanks partly to “weakened governance, impaired balance sheets and shift in focus … ascribed to state capture and corruption”, he said.

Weakening governance at SOEs —and also at departments and municipalities — became a key problem for the PICC, for which Patel’s department would become the secretariat.

“[It] limited the effectiveness of efforts to integrate projects to maximise their impact, or fund new projects in the… pipeline,” he said.

The stimulus plan will strengthen the PICC by, among other things, the development of technical capacity that can be drawn on by the dedicated infrastructure execution team to be set up in the presidency.

Fostering greater private-sector partnership will also be a key feature, said Patel, an example of which is the PICC teaming up with the civil engineering profession to identify infrastructure maintenance problems.

Added to this, the stimulus plan is addressing policy issues that have created bottlenecks, said Patel, including providing more regulatory clarity for the mining sector and finalising energy policy, notably the integrated resource plan.

A cursory examination of some of the major strategic infrastructure projects illustrates how they became associated with state capture and maladministration,rather than economic development and growth.

Transnet’s procurement of billions of rands worth of new rolling stock, which fell under the rubric of the development of a Durban-Free State-Gauteng logistics and industrial corridor, have become case studies for state capture.

The development of the Mzimvubu dam has been dogged by controversy about cost overruns and allegations of fishy funding plans.

Eskom’s construction of power stations Medupi, Kusile and Ingula was well under way before they were included as part of the strategic infrastructure projects.They have seen persistent delays and ballooning costs and the company itself has been brought to its knees by alleged corruption.

Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan also argues that things are different this time around.

Ahead of the stimulus plan’s launch the government had taken “decisive steps to rebuild investor confidence, confront corruption and state capture head-on, restore good governance at SOEs and strengthen… critical public institutions like Sars [the South African Revenue Service], the Hawks, the State Security Agency and the NPA [National Prosecuting Authority],” he told the M&G.

Changes at Eskom, “which was brought to the brink of collapse by state capture”, said Gordhan, are a case in point. The new board appointed in January, along with the new permanent chief executive, is instituting “a culture of effective and transparent governance, including ensuring that those who were engaged in fraudulent activities are brought to account”.

As a result there has been a positive change in investor sentiment towards the utility, he said. It was able to raise R43-billion between January and March, after previously being locked out of capital markets.

“The difference between this and previous interventions is that there is a determination and an urgency, led by President Ramaphosa,”said Gordhan.

The establishment of the South Africa Infrastructure Fund will reduce the current fragmentation of infrastructure spend and ensure more efficient and effective use of resources, said Gordhan.

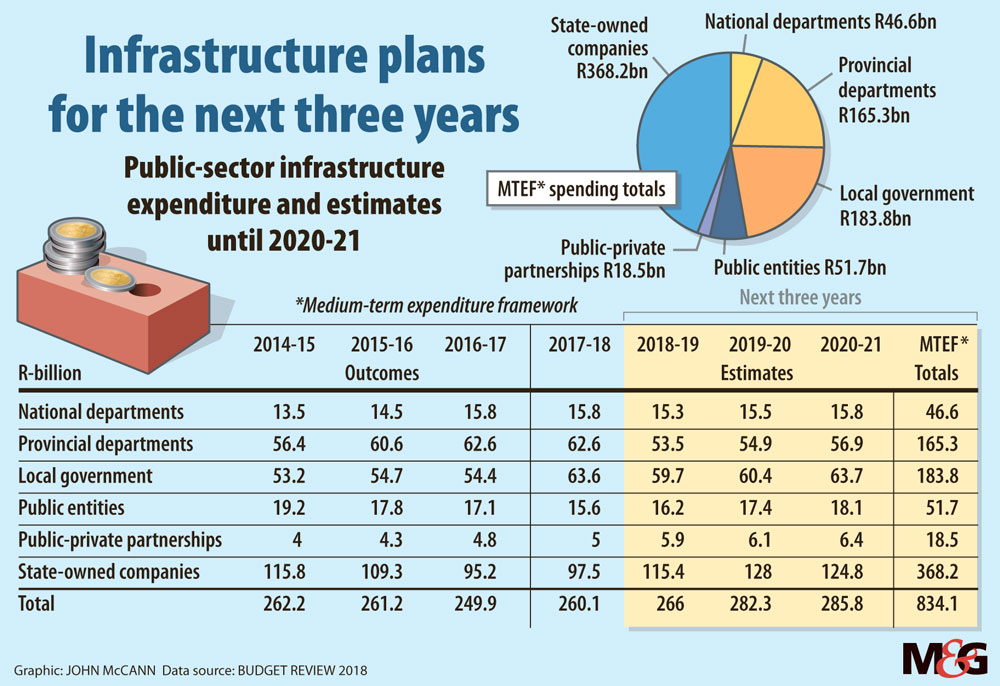

The R400-billion meant to seed the fund will, it appears, be made up largely by the infrastructure spend already budgeted for by the state over the next three years. About R834-billion for infrastructure was allocated in the February budget for this period.

But this includes spending by SOEs, other public entities and public-private partnerships. When these are excluded national, provincial and local government departments will spend a little over R395-billion on public-sector infrastructure.

The stimulus plan will also reprioritise R50-billion for job creation, health, education and social infrastructure improvement.

But where this money will be found is unclear, particularly given the already deep cuts announced in the budget in February driven by the introduction of fee-free higher education and declining tax revenues.New fiscal pressures must also be factored in, notably the recent public-sector wage settlement.

Credit ratings agency Fitch said this week that the plan is “unlikely to deliver a significant boost to economic growth”.

Several of the measures relate to existing proposals and others will take time to finalise and to have an effect, it said in a statement.

But the reprioritisation of spending could be positive for economic growth, said Azar Jammine, chief economist at Econometrix, particularly if there was “appropriate reprioritisation” away from wasteful, irregular and unauthorised expenditure.

Although government has made similar promises in the past, “under a new leadership we may be more successful in that regard”, said Jammine.

“The objectives and motives behind this are more genuine than they were in the past.”