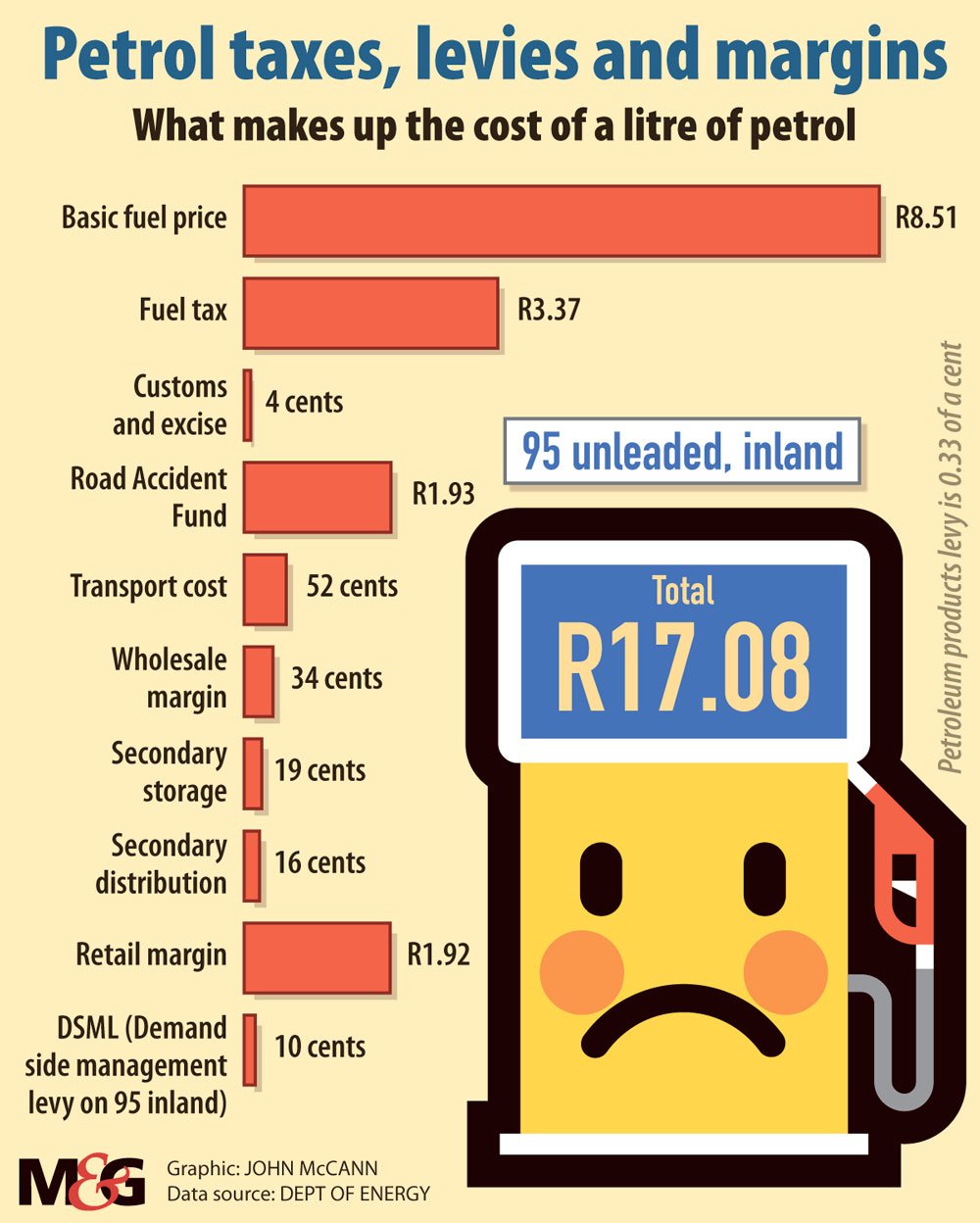

'If government doesnt have the fuel levy, it will have to recover the income the levy provides from somewhere else' (Graphic: John McCann)

The department of energy has started to review the fuel pricing formula, it emerged this week, as South Africans reeled from yet another round of record fuel price hikes.

“At the time, it was developed relevant to the prevailing market conditions,” says the director of fuel pricing in the department of energy, Robert Maake. “But the market dynamics have changed over time.”

The largest component is the basic fuel price, which was originally designed to protect and encourage local production, he says. Since it was designed in 2003 and implemented in 2004, it has not been reviewed. This and all other elements of the price at the pump will be included in the review.

Although a timeline for the review is not yet clear, the internal work on a discussion document has been completed and is awaiting approval, says Maake, after which it will be published for public comment. But the intention is to “have this implemented in the next financial year”.

“A parallel process to consider a sustainable mechanism that would be used to smooth the prices will be embarked upon as well,” he says. The department will inform the

public and all stakeholders about the two processes once approved internally.

As part of this process, the department will look at mechanisms in other countries, such as a stabilisation fund, a system in which the difference between the pump price and the fuel price goes into a fund. The department is discussing this with experts in the international pricing markets.

The fuel price went up on Wednesday. It is now 99c to R1 a litre more to buy petrol grades 93 and 95. Diesel increased by R1.24 a litre and illuminating paraffin by R1.04.

But the diesel price is not regulated and retailers can sell it at discounted rates. The figures published monthly are indicative of the price at wholesale level, says Maake, adding that the idea that retailers should be allowed to discount petrol as well amounts to deregulation.

If the government was to do this, several issues would have to be considered, including whether the “local petroleum industry is ready for deregulation”, he says.

South Africa has only a handful of major producers and, if prices are deregulated there is a risk that they will be dropped initially to get rid of small independent suppliers. “Once these smaller players are wiped out of the market, the oligopoly could then collude on prices,” he says.

Other concerns include the supply of fuel to remote and rural areas. Oil companies might find it too expensive to transport fuel to these places and close down service stations, creating supply problems. Alternatively “you might find fuel retailing for R30 [a litre] because it’s the only service station [in the region]”, Maake says.

The formula to calculate the basic fuel price includes factors such as aggregates from fuel refining centres in the Mediterranean, Singapore and the Arabian Gulf. The price also reflects fluctuations in the rand-dollar exchange rate and it is affected by geopolitical events around the world.

For instance, the United States sanctions on Iran since May have decreased the amount of crude oil available on the market. Iran, at 3.8-million barrels a day, is a major oil producer. These factors are largely out of the control of the South African government.

The state also adds the transport costs of the fuel, such as freight, insurance, ocean loss, cargo dues, coastal storage, stock financing and demurrage (an expense that is incurred when the cargo is delayed at a terminal). Most of these costs amount to 0.3% to 0.15% of the free- on-board value, which is the basic fuel price minus carriage and insurance costs.

Government levies such as the fuel levy and the Road Accident Fund levy are another key determinant of the fuel price. These are announced during the February budget speech and, unlike the basic fuel price, remain constant throughout the year.

These indirect taxes have increased exponentially in recent years, as the government has looked for ways to increase its revenue.

According to the Automobile Association’s spokesperson, Layton Beard: “When you look at the general fuel levy at R3.37 a litre (up from R3.15 last year) and the Road Accident Fund at R1.93, which add up to R5.30, there is a need to increase the figures but they should increase according to, or below, the increases in inflation. But that is not happening.

“If government doesn’t have the fuel levy, it will have to recover the income the levy provides from somewhere else,” Beard says.

According to the South African Petroleum Industry Association’s website, the fuel industry contributes R365-billion a year in turnover, earning R72-billion in duties and levies and R9.6-billion in capital expenditure (money spent acquiring or maintaining fixed assets).

Although political parties such as the Democratic Alliance have called for the scrapping of these levies, the government, and in particular the treasury, would have to find other income streams.