Toll: South Sudan rebels carry an injured comrade after a 2017 assault on government soldiers. Accurate statistics are hard to come by in places fraught with disasters and crises. (Goran Tomasevic/Reuters)

“How many dead?”

When journalists cover wars or epidemics or humanitarian disasters, this is often the first question they will ask. It’s morbid, sure, and not very sensitive, but the harsh truth is that, in a world of multiple, competing crises, death tolls are the easiest way to evaluate the severity — and, yes, the newsworthiness — of a particular situation.

It is a crude, often misleading shorthand that assumes that catastrophes can be reduced into a single number, and ordered accordingly. That doesn’t diminish the significance of the body count, however.

Death tolls are not just important to journalists. Governments need numbers to formulate policy. Humanitarian agencies rely on them to plan their responses and generate funding. Academics use them to frame their research. Politicians and activists use them to promote their particular agendas — and will often attempt to exaggerate or downplay the body count accordingly.

Given what is at stake, accurate statistics are vital. They are also difficult to come by. By their very nature, disaster and conflict zones are difficult places to do research. Record collection is usually a low priority when people are fighting to stay alive. Often local authorities will be in chaos and unable to provide the data. It may be too dangerous for researchers to go personally.

The longer a crisis continues, and the wider its effect, the more difficult the task of determining a death toll becomes. This is especially true of South Sudan, where a civil war has been raging since December 2013 — and where, until very recently, no one has had any clear sense of how many people have died as a result of the war.

“In complex conflicts like South Sudan, calculating the human cost of war is difficult,” said Kimberley Curtis of UN Dispatch, which provides coverage about the United Nations and the issues it is concerned with. “Lack of access throughout the country, inconsistent reporting and competing narratives from the warring sides makes it hard to confirm events as they occur.

“The UN gave its last estimate back in March 2016 when it estimated the death toll of at least 50 000. Despite further evidence of widespread ethnic cleansing, growing humanitarian catastrophe around food security, and a steady flow of refugees fleeing the country, the UN has never updated its estimate. It had essentially stopped trying to count, a fate that also befell the conflicts in Darfur and Syria.”

A group of statisticians from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine thought they could do better. Led by Francesco Checchi, who previously worked on a mortality study of Somalia, the four-person team crunched through whatever data they could get their hands on, applying sophisticated statistical techniques to extrapolate, cross-reference and estimate until they came up with a single figure.

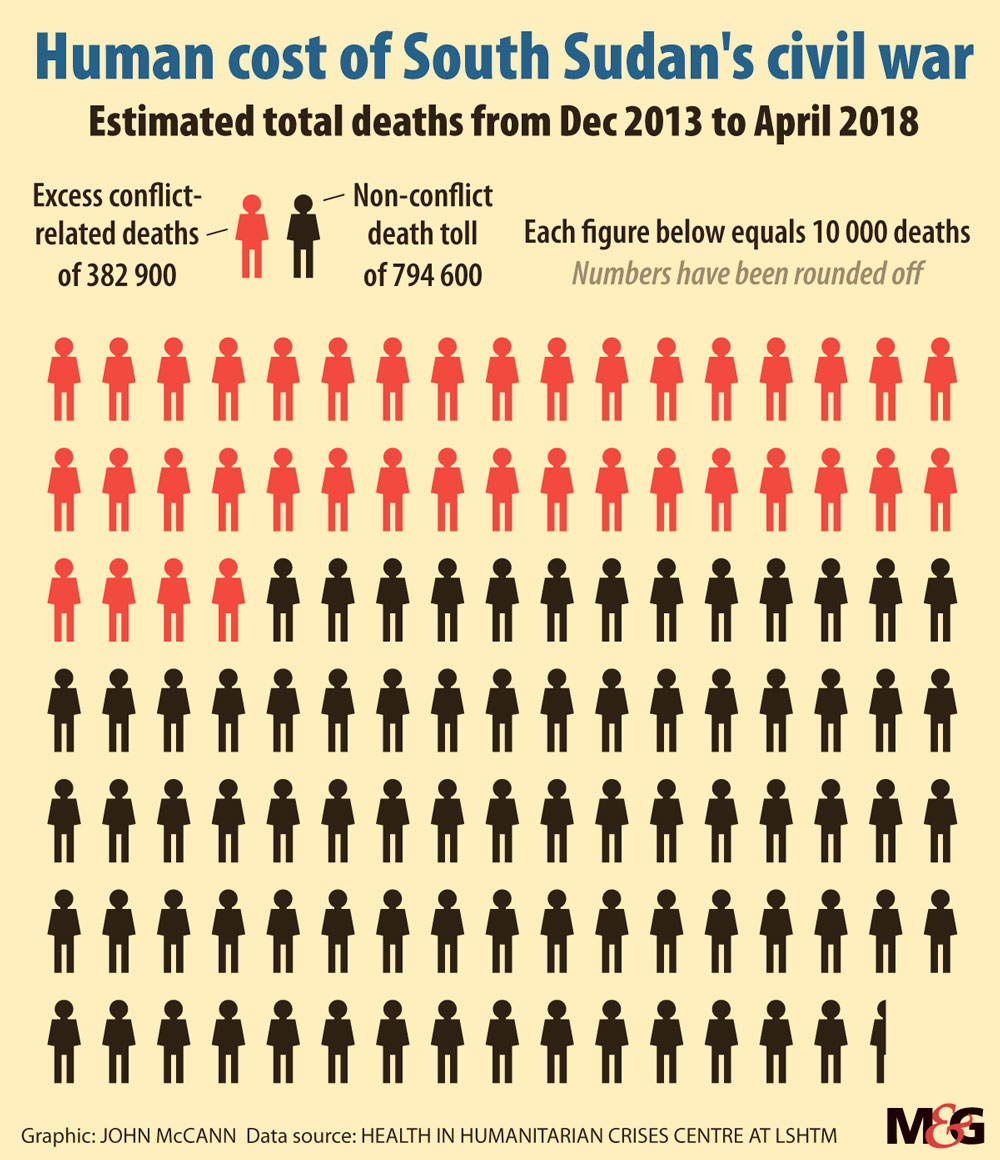

That figure is 382 900. That’s nearly eight times higher than the previous estimate of 50 000.

“Our findings illuminate the human cost of protracted conflict in South Sudan. They should spur warring parties and international actors to seek lasting conflict resolution, and, failing this, to conduct military action in accordance with international law,” the report concluded.

So how did they do it?

Well, it’s a bafflingly complicated process for non-statisticians. The Mail & Guardian has read the report — several times — and the finer details of the methodology are lost on us. A few things stand out, however.

The first is that the researchers use different variables as proxies for mortality: proxies such as rainfall, climate, how much food is grown, the price of food (measured as “amount in kilogrammes of white flour that an average medium goat can be exchanged for”) and the presence of disease. This is how it works: if there is low rainfall, they know that people will struggle to get water and grow crops, so deaths are likely to go up. Using data from all around the world, they can make an educated guess about how many deaths were caused by a specific deficit of rainfall.

These proxies are combined with the limited survey data available to give an overall death toll for South Sudan in the relevant period. But the war didn’t cause all those deaths. It didn’t even cause most of them. Many deaths can be attributed to old age and natural causes; others to poverty and diseases such as malaria that would have happened regardless of the conflict.

The next hurdle, then, is trying to figure out how many of these deaths were a result of the war itself, and how many are just part of normal life in South Sudan.

To work this out, the researchers constructed a “counterfactual” scenario, imagining what South Sudan would have looked like in the absence of a civil war. They present a table that outlines some of these counterfactual assumptions.

Beneath the dense academese is a heartbreaking portrait of what might have been. What if there had been no cholera, which is closely linked to the conflict? What if there were no violent clashes? What if people had been able to receive their measles vaccinations? What if the economy had not collapsed?

Once all these assumptions are plugged into the algorithm, the picture of mortality comes into focus and it makes for grim reading. “During the period December 2013 to April 2018, we estimate that 1 177 600 deaths due to any cause occurred among people living in South Sudan, and that 794 600 deaths would have occurred under counterfactual assumptions. This yields an excess death toll of 382 900.”

The researchers go on to break this down even further, finding that nearly half of this “excess death toll” is as a result of violent killings. “These and other estimates point to a conflict that, for civilians, has been even more violent than has been reported, and that has caused massive waves of displacement. Violence itself appears to be the key driver of overall mortality and of deaths indirectly attributable to the war.”

That’s why these numbers are so important, as gruesome as they may be, and as difficult as they are to come by. Because now we know that South Sudan’s war is even more violent than we thought. Now we know that it is far more deadly than even our worst-case scenarios. And now, hopefully, we can begin to do something about it.