A health worker hides their face while holding a placard detailing shortcomings at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in 2014. This year, workers' grievances became explosive with protests disrupting services in the North West and Gauteng. (Oupa Nkosi)

COMMENT

Historically, protest action has been the only social currency people could effectively use to overcome oppression. During apartheid South Africa, violent protests were an arguably justifiable response to the time’s illegitimate and oppressive regime.

Today, protest action continues to be a pillar of our democracy and is constitutionally protected through numerous rights: The rights to freedom of expression; to assemble, demonstrate, picket and make petitions, peacefully and unarmed; as well as to strike. These are essential human rights that should not be diminished or undermined.

But in the past few years, we have seen a growing trend in which during strikes, medical services are intentionally disrupted — healthcare professionals are harassed, intimidated and barred from rendering services. In many cases, facilities are either littered with filth or vandalised.

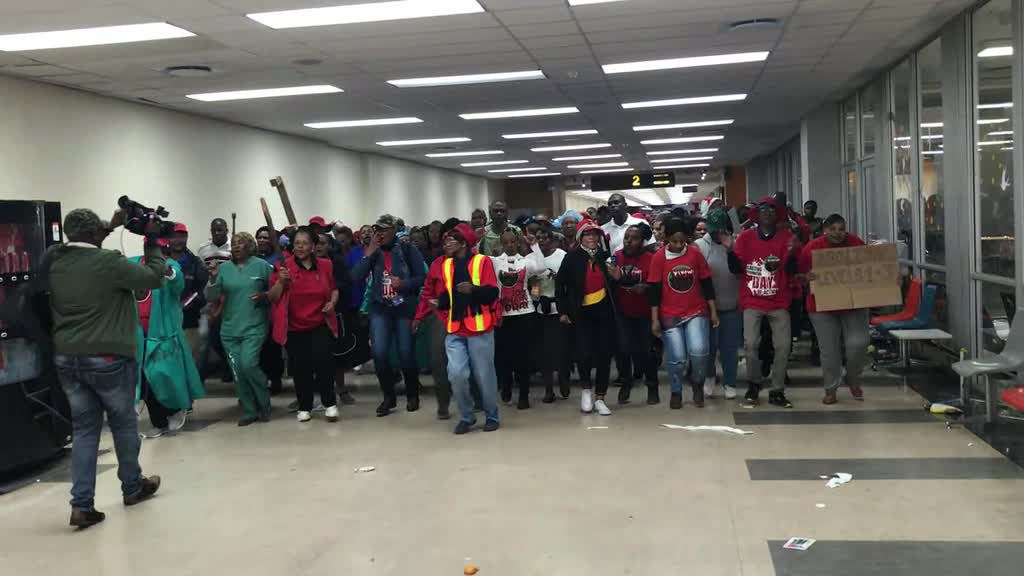

Healthcare in the North West was crippled earlier this year in part as healthcare workers protested corruption in the provincial health department. (Oupa Nkosi)

It is worrying that some South Africans who have taken an oath to protect patient lives are now among those who sometimes violate a patient’s constitutional right to healthcare and, more broadly, to life during protests.

These actions have also highlighted the interrelated nature of rights: Those of workers to strike and that of the public to access state healthcare.

Workers and their trade unions have a legitimate right to express their grievances by resorting to peaceful protest action.

In the South African Transport and Allied Workers’ Union judgment (2012), the Constitutional Court clearly set out the obligations of a trade union during protests, stating that: “At every stage in the process of planning, and during the gathering, organisers must always be satisfied of two things: that an act or omission causing damage is not reasonably foreseeable and that reasonable steps are continuously taken to ensure that the act or omission that becomes reasonably foreseeable is prevented.”

This brings to the fore the need to engage those who organise protests on their responsibilities during strike action. It may be worth remembering that protesters may be held liable for reasonably foreseeable and preventable damage caused by protests, according to Section 11 of the Regulation of Gatherings Act. Trade unions must educate members on not only their right to protest but their duty to ensure that demonstrations do not infringe on the rights of others to access services such as the right to work, the right to health and, above all, the right to life — one of the two most fundamental Constitutional Rights, as late Constitutional Court Judge Arthur Chaskalson explains in the 1995 judgement in S v Makwanyane.

“The rights to life and dignity are the most important of all human rights and the source of all other personal rights. By committing ourselves to a society founded on the recognition of human rights we are required to value these two rights above all others.”

The right to protest is an essential human right, but it is meaningless without the right to life.

We as a society must discuss ways to ensure that in promoting healthcare workers’ rights, we also protect and foster the public’s right to health. We need to develop a more definite sense of responsibility and understanding of how rights intersect, and how exercising them may impede the rights of others. In doing so, we must remember that one right should not unjustifiably infringe on or limit the rights of others.

Even during protest action, the public’s right to access healthcare services must be respected.

Healthcare workers protest at the entry of Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital in Johannesburg earlier this year over unpaid bonuses.

Yet recent violent protests at hospitals such as Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital in Johannesburg also reveal something more: People are resorting to political violence during demonstrations as a way of communicating their discontent.

We have normalised this type of violence, creating a space in which debate and the expression of dissent are legally permissible and should be tolerated, but many fear exercising their rights.

The government should see the desperation in this, in recent protests and their potential implications for fundamental human rights as well as their economic consequences.

Workers are the most essential component in the provision of healthcare. They deserve fair labour practices and equal protection under the law as their needs are addressed. This commitment should come loudly and clearly from the government.

The state cannot fail them and expect no consequences. Innocent lives cannot be put at risk for the failures of the government, especially when other legal alternatives exist.

Bongani Majola is the chairperson of the South African Human Rights Commission. Follow the commission on Twitter @SAHRCommission. To submit a complaint to the commission, go to sahrc.org.za