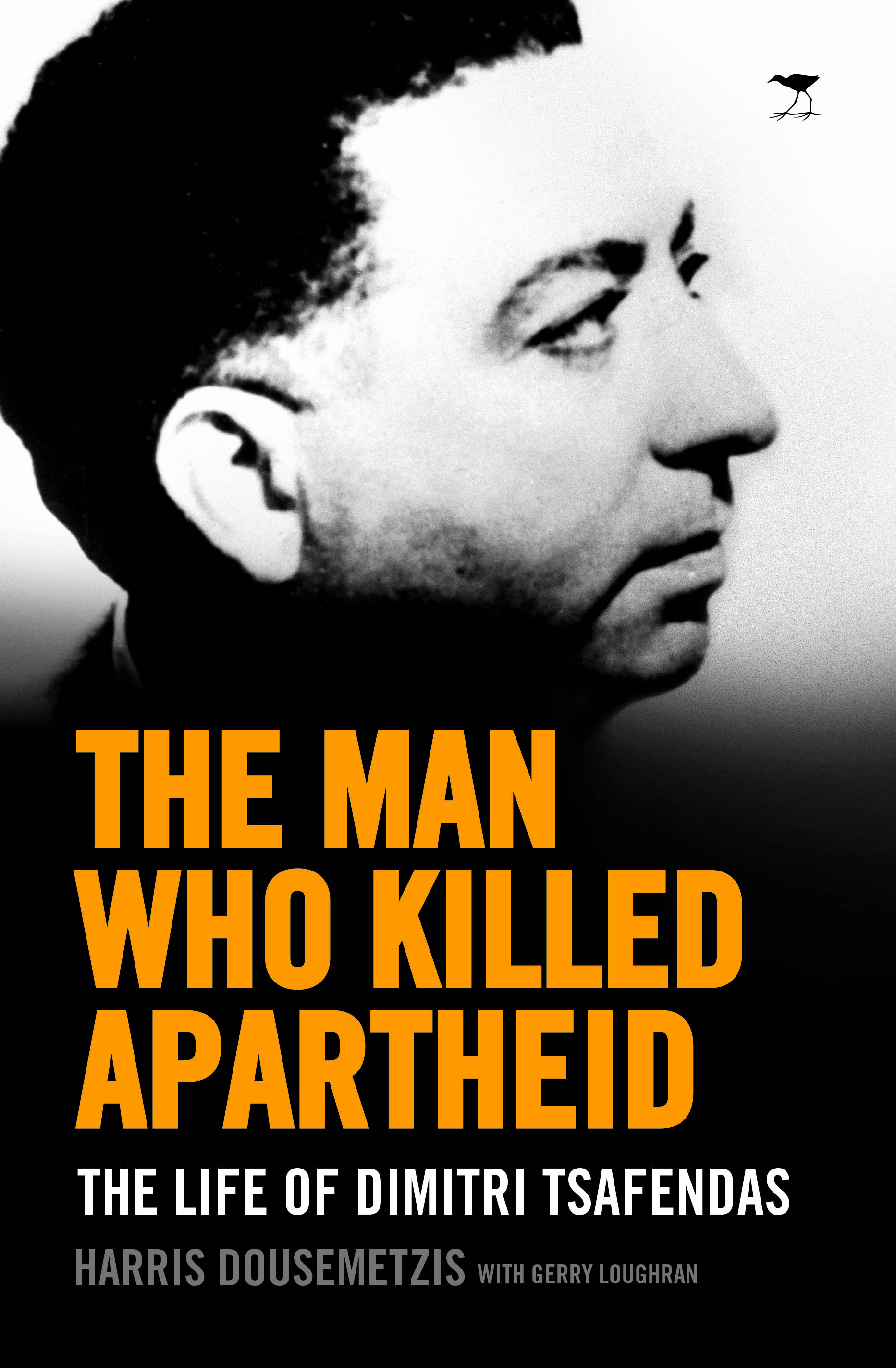

On reflection: Dimitri Tsafendas was sent to Sterkfontein mental hospital in Krugersdorp after years in prison (seen here in 1976). Photo: Courtesy of Gordon Winter

Harris Dousemetzis didn’t know about prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd’s assassin Dimitri Tsafendas, but he was aware of apartheid from a young age. Born in Greece in 1977 to a mother who was a passionate supporter of the ANC, Dousemetzis was pulled out of bed to witness the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990.

Dimitri Tsafendas stabbed Hendrik Verwoerd, the prime minister and ‘father of apartheid’, in September 1966.

“She told me who Mandela was, etcetera,” he says over the phone from the United Kingdom where he lectures in international relations.

Dousemetzis came across the assassin’s name in a Guardian obituary in 1999. Tsafendas, a parliamentary messenger when he killed Verwoerd in 1966, was declared insane and incarcerated for 33 years. He was born in the Portuguese colony of Mozambique to a Greek father and a racially mixed Mozambican mother.

Dousemetzis started learning more about him. This set into motion a process of revealing Tsafendas’s misunderstood role in the resistance against apartheid.

The author read A Mouthful of Glass: The Man Who Killed the Father of Apartheid by Henk van Woerden and came across an article in a British newspaper headlined “The man who killed apartheid”. The article was a sidebar to a spread about Greeks who had collaborated with and financed apartheid.

He then contacted some of the clerics featured in a Greek documentary about Tsafendas. He says what they said was nothing short of astonishing. “They were praising Tsafendas, in the highest possible terms,” he says. “Two of them considered Tsafendas to be a great hero, which was highly unusual for Christian Orthodox priests.”

He trawled through the archives in Portugal and South Africa.

“Everything said by witnesses to me, that Tsafendas was a political animal since he was a child, was confirmed by what was found in the archives,” he said. “I felt it was a major injustice against him … It was an absolute disgrace to think Tsafendas was mad and that he killed Verwoerd because of a tapeworm.”

In this interview, he tells the Mail & Guardian of his mission and book.

How did you begin writing the book from all the various pieces of information you were gathering?

I thought for some time to write a book about Tsafendas, but then I thought just a book will not be enough to change people’s minds. I decided to take all the evidence that I gathered to the South African authorities and ask them to look at it. I figured I should present the evidence to some reputable South African jurists, so I contacted seven. Five of them agreed to look at my evidence and to collaborate with me in order to write an official report which would be submitted to the minister of justice.

They wrote to the minister of justice, asking him to look at the new evidence, make an official announcement accepting the new evidence and to take steps to correct the historical record.

Why did you feel so strongly?

I just felt it was a major injustice. I felt it was an absolute disgrace that Tsafendas is considered insane. It is an absolute disgrace that people believe a lie that was created by the apartheid regime 52 years ago. The people I spoke to spoke so highly of Tsafendas, which was very emotional.

What happened to Tsafendas and the way he was treated by the apartheid regime also played a role. Tsafendas told two priests who visited him: “Every day, you see a man committing a very serious crime for which millions of people suffer. You cannot take him to court or report him because he is the law in the country. Would you remain silent and let him continue with his crime or would you do something to stop him?” He felt it was his duty to do this. Somehow, I felt it was my duty too, since I knew the truth about Tsafendas. The priests didn’t speak publicly about Tsafendas because he told them not to because he was a humble man. He believed he should not get praise for what he did because it would undermine the value and the dignity of his deed.

Don’t you think it was naive of him to believe that, by murdering Verwoerd, he could strike a blow against apartheid?

He considered Verwoerd to be the brains behind apartheid, which he was. If you look at history you will see that, soon after a leader dies, the empire or country collapses. The most shining example of that is Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia, while Josip Broz Tito was president, was a united, strong country. As soon as Tito died in 1980, the first cracks appear and it took only nine years for the country to collapse.

Tsafendas admitted that he did not believe that apartheid would collapse soon, but on the other hand he didn’t expect that it would take 28 years. But it wasn’t only that he expected apartheid to collapse. He wanted to punish Verwoerd for what he was doing.

Why do you think this lie persisted for so many decades?

It’s very easy. It’s not only Tsafendas. Ahmed Timol’s death was considered a suicide until last year. The commission of inquiry into Sharpeville was accepted as fact until the TRC [Truth and Reconciliation Commission], which overruled the findings. From 1960 to 1996, people believed apartheid’s official version.

The commission of inquiry into Tsafendas gives the most inaccurate and most distorted picture of events ever and we are going to make a request to the court once the minister has agreed with the findings, to set aside the findings of the commission of inquiry. Both Judge [Jacques Theodore] van Wyk, who led the commission of inquiry, as well as the attorney general in Tsafendas’ trial, who was also the public prosecutor, manipulated the evidence in order to present Tsafendas the way they wanted.

The attorney general lied in the trial and afterwards about Tsafendas. The attorney general wrote a memorandum saying that Tsafendas was arrested twice for communist activities in 1938 in Mozambique. Then he wrote that in 1939, when he came to South Africa he became a member of the South Africa, Communist Party. In the trial, the fact that Tsafendas was a communist was not mentioned in the court and the attorney general lied to a journalist about knowing this when asked afterwards.

What was your method in creating an engaging story?

It was easy to write the book because I first wrote the report. I based the report, to a certain extent, on what happened to Tsafendas in prison and what happened to Tsafendas in the hospital. The report is primarily about the assassination.

So because I had the bones, what was necessary was to put on the flesh in order to turn it into a book, but the only difficult part was that I had so much information and a lot of things had to be left out. I would need to write another book about his life.

So did you start with bulk and whittle down ruthlessly?

Firstly, I had the interviews, and was making thorough notes so by the end of each interview I knew exactly what I was going to use from what they told me.

When I got the documents from the archives, most of them needed to be translated from Portuguese. The South African ones were in Afrikaans, and I cannot speak the language, so there was a lot of translation. But many of these documents were not relevant to the case or were of secondary importance.

So, while writing the report I made notes of what can go to the book. So I kept putting those aside. I used the biographical information in the report as a base. I also digitised all the documents from the archives and titled them so that I knew what each one was about; that’s why there is such thorough referencing in the book.

The Man Who Killed Apartheid: The Life of Dimitri Tsafendas is published by Jacana