Trendsetters: Trompies members Zynne Sibika (left), Jairus Nkwe, Eugene Mthethwa and Mandla Mofokeng. Photo: Sydney Seshibedi/Gallo Images/Sunday Times

The death or otherwise of kwaito is up for debate. The originators of this music form, such as the Trompies, Mdu and B.O.P, insist that the cultural phenomenon that was once (if not still) the soul of post-apartheid popular culture has not died, it merely took on new forms, as any culture should. They also say kwaito will survive as long as there are townships in South Africa — in other words, the music will live on as long as the conditions that created it still exist.

Many are of the view that the Sowetan sensibilities we once knew from the sound are no more. The slow-tempo bass ’n drum accompaniment to the hardcore joyful-lamenting lyrics of kasi living are catching dust in zones of nostalgic frenzy, they say. In the public perception (at parties and the like), the music is considered an old-school moment, a music for reminiscing.

No one cares to know what kwaito song is hot at the moment, people seem only to be interested in the classics — Mandoza, Zola, Mdu, Brown Dash, Spikiri — except if they hear in the new sounds something similar to the old sounds.

Boundaries have been widened (arguably) and a new breed of pantsulas (kwaito men and women) has emerged, self-appointed, to take up the task to preserve and continue the music. “Kwaito is not dead, it evolved; it is now new-age kwaito, bruh,” they say.

Fair enough.

In what we could call the golden age of kwaito, this new breed of pantsulas occupied the category of aboMrapper, a detested group of American wannabes — “amakoporosh”. For the golden age pantsula, aboMrapper could not fit into the rough-and-ready pantsula image that was demanded from a kwaito figure. They spoke too much English and gibberish — a sign of weakness and affluence; their “swag and slang” was alien to what was understood. Abo-Mrapper’s image was in contradiction to the kwaito sensibility that privileged the mastery of marginality of “olova” and “oguluva” — the quintessential hustlers. As the influence of hip-hop grew globally, attitudes towards it changed and aboMrapper gained access to the kwaito subculture by demonstrating that they, too, were hard-core hustlers fit for the pantsula label.

The year is 2018 …

The new pantsulas (aboMrapper) are trying to convince us that the preservation and continuity of kwaito will happen by way of “sampling” kwaito “classics”. To the new pantsula, sampling seems to be an appropriate model for composing and continuing kwaito music.

Spirit: Kwesta is one of the successful new pantsulas taking Kwaito forward by adding to it. Photo: John Wessels/ Gallo Images

I am sceptical about the sincerity of this process. In popular music cultures such as hip-hop and kwaito, sampling is used as a democratic music-making way to displace previous and sometimes conservative music production methods predicated on the centrality of live musicians. Through this process music-making as a vocation is made available to those who do not necessarily have the opportunities because of a shortage of resources.

As observed by Bheki Peterson, head of African literature at the University of the Witwatersrand, sampling could also be viewed as a method to “renew past musical milestones, updating them to make them sound fresh in the present”. In this process producers and artists “cultivate a realm of musical preservation while embedding their own creativity into the original song’s creative legacy”.

Although unannounced, the creative genius is measured by the degree to which the new track artistically modifies or supplements the original. The producer sometimes samples from a different genre and era, which serves two functions: first, to bring audiences of that other genre to this new music (kwaito) and, second, to present the listener of the new music (kwaito) to the musical worlds travelled by the particular artist/producer to create the new sound.

Msawawa’s Bowungakanani and TKZee’s Shibobo are a case in point.

My suspicion is that this sampling relationship between the new pantsula and golden-age kwaito operates in an exploitative manner.

If we argue that kwaito is not dead, that it took new forms, then we must be willing to regard the golden-age kwaito and the new pantsula kwaito or new-age kwaito as contemporaries, operating in one temporality — this spacious present of post-apartheid South Africa.

If we agree with this proposition, then we should remember that, in kwaito and hip-hop cultures, the “sampling” and “chopping” of contemporary’s music is considered as “biting” or “ukugawula” (plagiarism; see Magawula by B.O.P).

Therefore, the new pantsula cannot justify their perpetuating the kwaito sound by the current musical practices they undertake. In their songs and music videos, the new pantsula assembles kwaito tropes and imagery rhetorically — from lyrics and beat to costume and dance — without any display of commitment to the furtherance and variation of the music.

The new pantsula knows very well that no other music has captured the imagination of post-apartheid South Africa in the manner that kwaito did, and that is why they will sample the kwaito song in such a way that it won’t be mistaken for anything else (taking the song as it is).

The manner in which the new pantsula deals with kwaito exploits the cultures that make up the sound without any sign of commitment.

For example, in his 2017 Stay Shining music video and song, Riky Rick makes a visual reference to TKZee’s We Love This Place and Dlala Mapantsula to such an extent that he couldn’t conceal the borrowed lines from Kabelo Mabalane’s Pantsula for Life.

Riky Rick’s work has seen him making visual references to TKZee. Photo: Frennie Shivambu/ Gallo Images

He is not alone; there are many others, from Cassper Nyovest to Major League. These could be deliberate moves, but do we call Riky Rick and company “creative” for reiterating to us a moment that has not escaped our memory?

I doubt it.

My view is that kwaito music cannot be sustained in the manner that it is happening (sampling the self). Possibilities should be extended and explored by the new pantsula in the same manner that kwaito emerged in the early 1990s.

If kwaito is still alive and healthy, we should be able to detect it from the current panstula musical practices without the help of these sampling methods.

To convince us that they are serious about the continuity and preservation of kwaito, the new pantsula should be able to do a song without using a line or verse from a golden- age kwaito or house song.

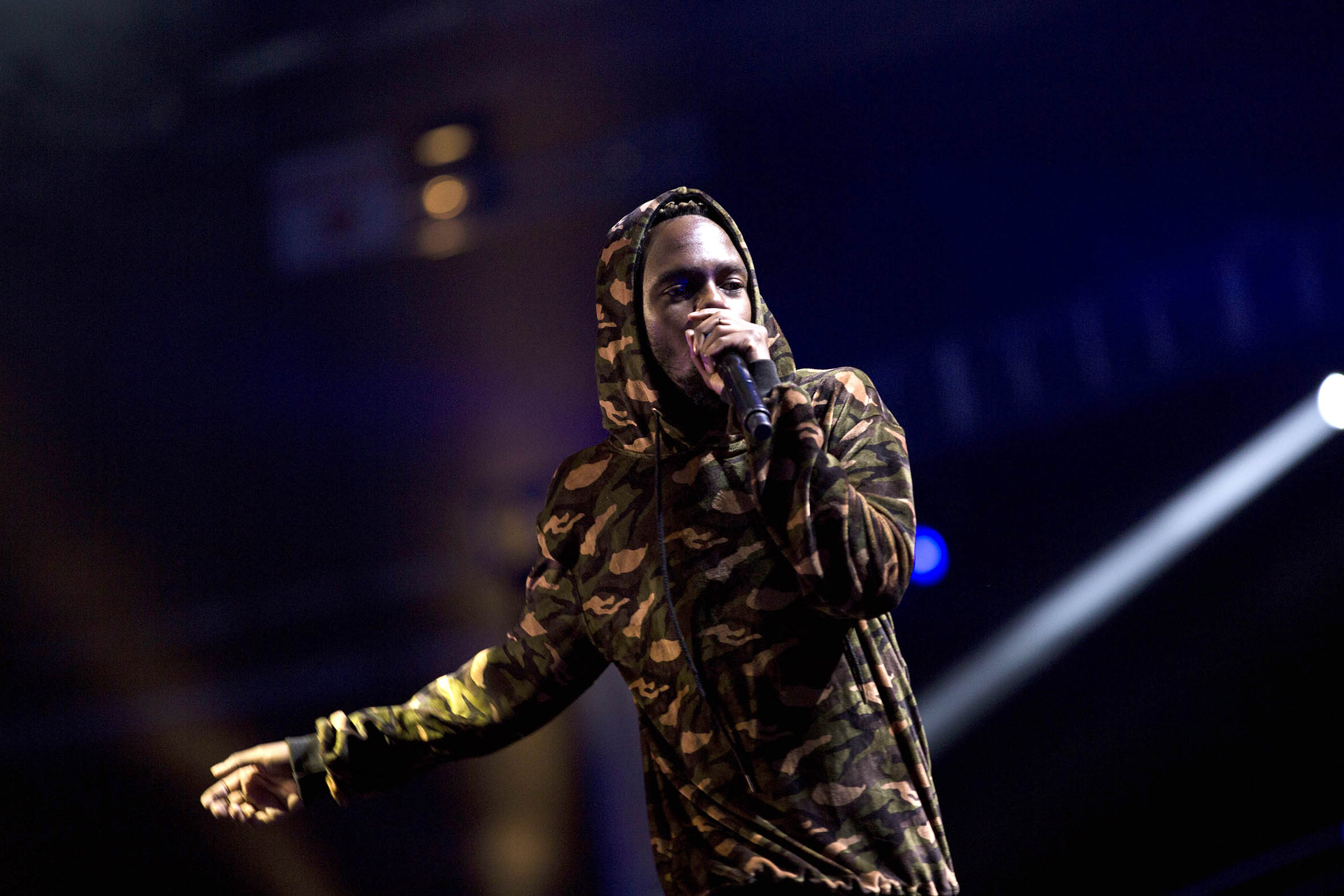

Not all hope is lost, though. There are some new pantsulas who display commitment to the development of this sound in ways that are not so exploitative. These new pantsulas have inflected their interventions with more hip-hop influenced approaches — and I think the reason their sound always works is that it goes back to the source (kwaito/ kasi). Think, for example, of Kwesta’s success.