Leah Karegeya, the widow of Patrick Karegeya, who was murdered by suspected Rwandan assassins, hopes the police can bring his killers to justice. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

In the restaurant of the Michelangelo Hotel in Sandton, a worried David Batenga sipped on his beer as he waited. He had been pacing the hotel since noon, looking carefully at each of the passers-by who walked through the spacious marble lobby. He was looking for the guest in room 905. It was almost 8pm.

Batenga had been barred from entering the room. A “Do Not Disturb” sign was hanging on the door. Eventually overcome by anxiety, Batenga insisted that hotel staff open the room. He knew the guest who had booked that room was nearby. The blue Audi A5 belonging to him was in the parking lot. The staff relented, but refused to allow Batenga on to the ninth floor.

David Batenga, Patrick Karegeya’s nephew, had to identify his uncle’s body as it lay in room 905 at the Michelangelo Hotel in Sandton on New Year’s Day 2014. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

In room 905, former Rwandan spy boss Patrick Karegeya lay on his back on the bed. His skin was discoloured. His shirt was unbuttoned to just below his chest. But the staff member saw none of this. From the doorway to the room, she could only see his legs on the bed. She quickly shut the door.

“The guest is resting,” Batenga remembered her telling him.

He demanded to see Karegeya, but the staff at the reception desk refused. He insisted. They told him they would have to call the police to give him access.

Batenga waited in the restaurant until the police arrived and entered room 905. They found 53-year-old Karegeya dead. From his discoloured complexion, it was clear that hours had passed since his death. He had been strangled.

It was January 1 2014 and, in the final hours of December 2013, the Karegeya family had raised alarm bells that Patrick was not answering his phone. His family describe him as a festive man who would have sent them New Year’s text messages. But that year, he had been silent. This is why his nephew, Batenga, was frantically trying to find him.

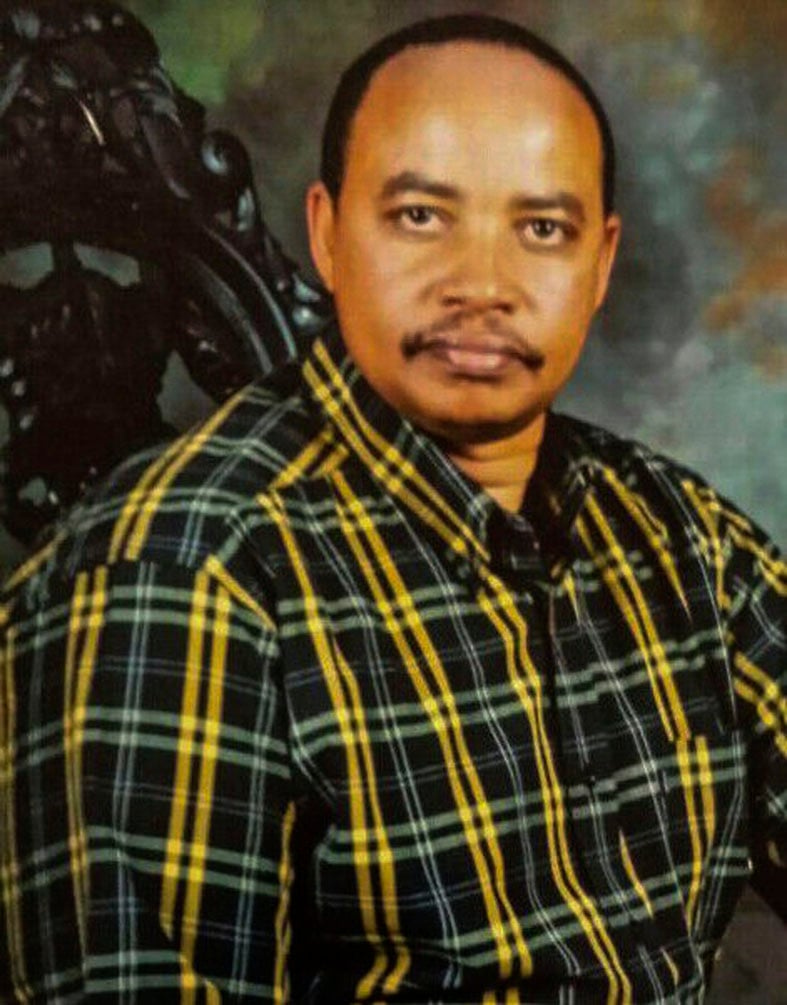

Patrick Karegeya

A hotel staff member approached Batenga in the restaurant.

“The guest is deceased,” Batenga remembered her saying.

In his shock, he became confused. He walked into the elevator. It slowly glided to the ninth floor. In the hallway, police accompanied him to identify his uncle’s body. The TV was blaring loudly. When Batenga looked into the spacious room, already declared a crime scene, he saw his uncle’s legs on the bed. As he walked in further, he saw the rest of the body.

“His face looked like charcoal. I recognised the shirt he wore; the wallet and the keys were there but he was unrecognisable,” Batenga said.

In the next few hours, a domino reaction would begin. Batenga would tell his wife in Irene, near Pretoria, about his uncle’s death. His wife would call Leah Karegeya, Patrick’s wife, in Maryland in the United States, and Leah would struggle with how to break the news to her three children. She had left South Africa because of the threats her family had received. Over the next few days, the hotel room was under a global microscope. Headlines would blare out about Karegeya, the Rwandan dissident who had been murdered, allegedly by a death squad carrying out a swift extrajudicial operation.

It was a case that would draw attention to South Africa’s own law enforcement and the delays in justice for a family that had suffered what they believe was a politically motivated assassination. Karegeya, a former colonel, was once a close friend of Rwandan President Paul Kagame, but the two fell out. Karegeya was imprisoned twice and stripped of his military rank after he criticised Kagame’s regime.

Eventually, Karegeya, who was also Rwanda’s external spy chief, was forced to flee. He sought asylum in Johannesburg, where he was killed.

But that was five years ago. Since then, the Hawks have prepared a docket that points definitively to who the suspects are. All four are Rwandans who left South Africa shortly after the murder. Their passport numbers are known to the police, but no warrants of arrest have been issued.

The National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) has declined to prosecute. Faced with no criminal procedure, the family has accused the NPA and police of deliberately delaying the case because of the “irresistible inference of political meddling or a prohibition to proficiently investigate the identified perpetrators”.

An inquest, which was expected to begin last week, has brought Karegeya’s murder back into the spotlight.

But, on Monday, in a dramatic turn that stunned those gathered in the small, nondescript courtroom, magistrate Jeremiah Matopa halted the inquest. He struck the case from the roll pending further investigation. The investigators, he said, had started the investigation “like a house on fire”, but failed to do their jobs properly. It was a ruling that gave credence to the family’s concerns.

“The magistrate is therefore removing this matter from the roll due to a number of outstanding statements, documents and information that require to be investigated,” Matopa said in his ruling at the Randburg magistrate’s court.

His ruling also delivered a bombshell confirmation: a letter submitted to the court and written by the NPA in June last year showed it knew that “close links exist” between the suspects and the Rwandan government.

The family believed from the outset that Karegeya was murdered on instructions from the Kagame government and they believed South African authorities were aware of it. They believe the ruling has vindicated them and given them some form of closure.

But further justice will be hard to come by. South Africa does not have an extradition treaty with Rwanda. Ironically, Karegeya came to South Africa because he knew he could not be extradited if the Rwandan government wanted to arrest him. Now that may work against his family.

But Kennedy Gihana, the family’s attorney, says that South Africa still has other ways to secure the suspects’ arrests.

“Even if there is no extradition treaty, they can do it formally to request the Rwandan government to hand in those people to come and stand trial,” Gihana says.

The investigation into Karegeya’s death was also hindered by what the magistrate referred to as “discrepancies”. In his ruling, he revealed that a forensic laboratory in Pretoria had been concerned about inconsistencies connected to two sealed evidence bags. There was also another piece of evidence that had a “discrepancy”. But when these concerns were raised with the police, it appears there was no response, according to the magistrate.

The police now have 14 days to explain to the magistrate what steps they have taken to arrest the suspects and the discrepancies in the evidence, according to Matopa’s ruling. They also need to submit original statements, which Matopa found to be missing from the docket.

While the hunt has been on to find Karegeya’s killers, General Kayumba Nyamwasa, a close friend of Karegeya who also fled Rwanda and sought asylum in South Africa, has been looking over his shoulder.

For him, South Africa is one of the “hunting grounds” in the world where Kagame’s regime targets dissidents. The general has survived two attempts on his life in South Africa. In June 2010, he was shot in the stomach in Johannesburg.

After the second attempt, less than three months after Karegeya was killed, the South African government expelled four Rwandan diplomats. In a statement, the South African government would link the Rwandan embassy with the sinister men who killed Karegeya.

“The inquest is important so that South Africa understands the government it is dealing with,” Nyamwasa says.

He and Karegeya were the founders of the Rwandan National Congress, an opposition political party in exile.

In court on Monday, Leah was flanked by members of the party as they waited for news about the case.

Before they started the party, both men had been closely involved in Kagame’s administration. Nyamwasa says that, during the wars in Kisangani in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in the late 1990s, he was employed in the police and had nothing to do with the military or state operations in the wars. But Karegeya, as the spy boss, was accused of organising intelligence that resulted in the killing of many Ugandan soldiers and possibly also civilians caught in the crossfire.

His family are adamant he is innocent of wrongdoing and was not involved in the wars, but Karegeya admitted in an interview with the Ugandan newspaper The Observer that he “co-ordinated intelligence” during the fighting between Rwanda and Uganda in the DRC.

In the same interview, he said he had fallen out with Kagame because of the dictatorial regime the Rwandan president was cultivating.

“We fought for the liberation of Rwanda so that Rwandans can enjoy peace and be delivered from dictatorship but we have not seen that,” he said.

For Nyamwasa, Kagame has created a world network of “hunting grounds” for dissidents. He believes that Rwandans around the world live in fear of the regime.

In 2017, Human Rights Watch released a report that highlighted the harassment of and attacks on “opponents and critics” of the regime living outside the country by the Rwandan Patriotic Front, Kagame’s ruling party. The report claimed that there had been killings of dissidents abroad.

Leah spoke to one of the men accused of her husband’s killing on at least one occasion over Skype before his death. She met him while speaking to Patrick. She can’t remember much about the details, but she knows his face. The man frequently met Karegeya and is suspected of being part of a trap to have him killed.

The police know the name of the man and they will now have to explain to the court what they have done to locate him.

For the Karegeya family, it’s another delay, but they hope it will force South Africa’s law enforcers to undertake a thorough investigation.

“It is something I have been praying for for a long time,” Leah says.

This article’s headline and blurb have been amended.