The Qwaninga River that feeds the Qwaninga treatment plant has been reduced to a trickle, exposing beds of rock and sand where water should have been. (Photos: Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Winding through the valleys of the Eastern Cape, the Qwaninga River creeps towards a cluster of buildings hidden deep in the hills. It licks the rocks, but doesn’t wash over them and it struggles to stretch across the sandy ground it would usually cover.

The river stops just before it reaches the buildings. The rocks are bare. They are bone dry.

The buildings are the Qwaninga water treatment plant. It is here where water is purified and pumped out to supply the 26 villages in the Mbashe local municipality. The villagers rely on the river.

“This is where we used to get the water before,” says Bongani Malope from where he stands in the rocky river bed. Malope, who works at the plant, did not want his real name to be used.

Workers still live at the treatment plant but there is no water to treat. It has been this way since September last year.

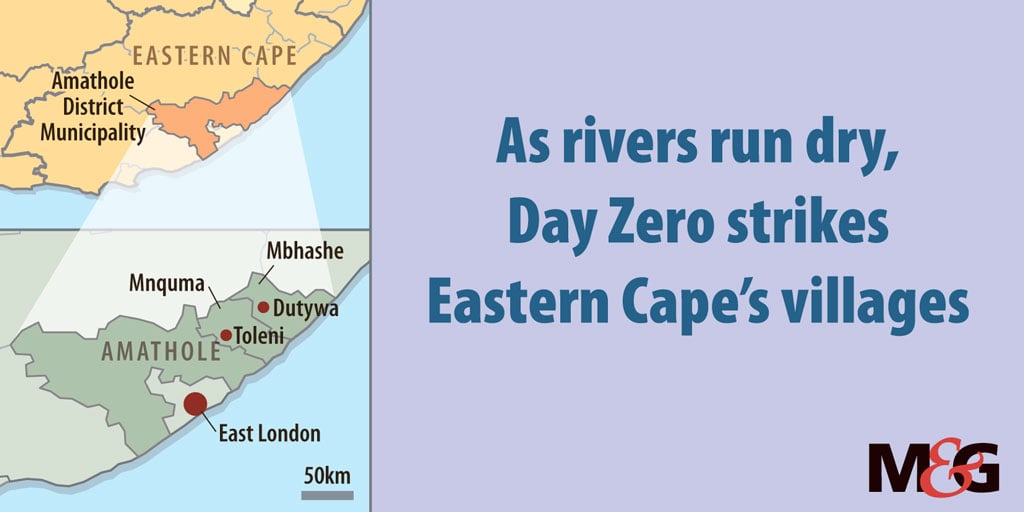

The Amathole district municipality, which is responsible for six local municipalities including Mbashe, has been struck by a devastating drought. In the quiet peri-urban towns water is shut off for days in an effort to conserve the trickle that remains. Day Zero has silently and violently hit poor areas that do not have an alternative source of water.

The fields that sustain the villagers of Mbashe are no longer productive

Malope believes that rain is the only element to turn the situation around. In retrospect, he can see some of the mistakes that have been made: if there had been a dam to store water, for example, then maybe it wouldn’t have run out so soon. Water here has always been harvested directly from the river.

The desperate efforts of workers can be seen. They have dug furrows to try to encourage the remaining water to flow up into the treatment plant, but to no avail.

In the first week of February, the Mail & Guardian visited the Qwaninga River and the Toleni Dam, another water source in the district. The dam, which supplies the Mnquma local municipality next door to Mbashe, is so low that it is possible to stand in its centre.

An official working at the dam fears that it will become a desert.

As technicians and engineers watch helplessly, the district municipality is unsure about how to provide water when drought is affecting every one of its regions. The Amathole district municipality is also technically bankrupt.

People have to walk long distances to collect water if they are able to. Everyone who can afford a rainwater tank relies on it, even for drinking water, when the taps go off.

The dry village

Ivy Ndumiso walks slowly outside her rondavel. The house is surrounded by small plastic drums positioned on the ground below the edge of her roof. Beads of rainwater stick to the roof, but do not yet drip into the buckets Ndumiso desperately needs to fill.

Rain is the only hope for Ivy Ndumiso, who has had to resort to collecting drinking water from puddles and catching water in buckets from her rondavel’s roof

She relies on water that comes from the Qwaninga River. But she does not know that the river is dry. From her house, in a village about 2km from the treatment plant, she cannot see that there is no water to be pumped to her village. All that she does know is that the tap does not work.

Her home is slightly isolated from the rest of the houses scattered in the village. Some people in this village have tanks in which they store rain water to use for drinking and cooking. But Ndumiso cannot afford a tank. With the tap dry, and no alternative sources of water nearby, her situation is dire.

“I rely on the water in the ditches in the road. The water is so smelly. I am coughing because I don’t have clean water to drink,” she says.

The water she speaks of is found in the puddles that gather in potholes or other gaps at the side of the dirt road in her village. She sometimes even collects the water that animals have used.

“Sometimes even some cows used to urinate on this water but we still fetch and drink it because we don’t have a choice,” she says.

Ndumiso’s exact birth date is unknown, but she says she was born in a year when there was a locust invasion. A guess is that she was born in the 1930s, making her at least 80 years old. She can no longer walk to collect water, and the water from the side of the road has made her ill.

Her frail body is covered in warm clothes, but on her bare feet a rash spreads out like a spider’s web. She believes it is a consequence of using dirty water to wash after she hurt herself. Although she was given an injection at the clinic to tame the pain, the rash now covers her body.

One Amathole district official confirmed that the joint operational centre tasked with responding to the drought is aware that clinics are treating people for water-related illnesses.

For Ndumiso, this is not the first time the taps have dried up. But it is the first time that there is no other water source. In 2010, when the Qwaninga was dry, she says the municipality came with water tankers and provided rainwater tanks. Now, there is nothing.

“I don’t know why there are no trucks or Jojo tanks,” she says.

We knew about it

In June 2017, Thandekile Mnyimba was appointed as the manager of the Amathole district municipality. He has a history of being sent to manage troubled regions. In his own words, he is meant to be the “turnaround guy”.

Thandekile Mnyimba was brought in as water manager of the Amathole municipality in the hope that he will find solutions

But the problem he is tasked with fixing in Amathole was predicted

10 years ago. In an interview with the M&G, Mnyimba admitted that the department of water and sanitation and the Eastern Cape department of co-operative governance and traditional affairs had forecast drought in the province as far back as 2008.

“When I started to be a municipal manager in 2008, in one of the smaller municipalities, called iKhwezi municipality, the Eastern Cape was already experiencing drought and within the Eastern Cape drought was declared,” he said.

“As Amathole, we declared drought in 2014 and since then we’ve been re-declaring drought,” he said.

Three weeks ago, Mnyimba was informed that Mbashe municipality is dry — almost five months after the fact. He realises that officials in the municipality have to take some responsibility for the catastrophe.

“Our people are on Day Zero. They have been on Day Zero donkey years ago. Perhaps we did not make enough noise to bring it to the level that the Western Cape has mastered out of Day Zero.”

Mnyimba says that he is waiting for his technical team to provide guidance on what to do because even nearby alternative sources of water have been severely affected by the drought. Mnquma local municipality — the closest source of water for Mbashe — is the second-hardest hit and cannot afford to supply water to its neighbour.

“It’s like saying the poor must subsidise the poor,” Mnyimba says.

The Amathole municipality applied for R122-million in funding from treasury through the Eastern Cape co-operative governance department in 2018. Although treasury agreed to release R64-million, the department has not transferred the money yet.

“We wrote to them in December reminding them to transfer the funds,” he said.

Mamkeli Ngam, the spokesperson for the co-operative governance department said treasury had not effected the transfer. Ngam added that the department had provided Amathole with R3-million to respond to the drought and that research was being done with the Water Research Commission on alternative methods to deal with the drought and mitigating future drought.

The neighbours

In the Mnquma area, villagers feel panicked as they watch the Toleni Dam run dry.

Toleni Dam has been reduced to a trickle, exposing beds of rock and sand where water should have been.

In the middle of the dam, sandbanks rise above the dwindling water. An official says the dam is 17% full. On a good day, the dam should provide 1.6 megalitres (the equivalent of 1.6-million one-litre bottles of water). But things are bad, and the dam — with the help of a nearby borehole built by the Amathole municipality — can only supply just over 0.6 megalitres.

A borehole provided by the Amathole district municipality was sunk to help supply water to the Toleni area

“It’s scary,” says Buhle Madikizela, a municipal official, who also did not want his real name used.

Like their counterparts at the Qwaninga River, technicians have exhausted their options in trying to harvest more water from the dam. The furrows dug in the hope of channelling water to the Toleni treatment plant can be seen in the sandy ground.

Above the dam, houses belonging to villagers dot the hilly horizon. The village, Toleni R41, has been there for many years. Older people can remember when there was only a river; no dam had yet been built. Now they watch as it all evaporates.

Nozukile Centane (69) remembers playing at the river as a child. She remembers a girlhood of water in abundance. But she knows that climate change has paved the way to a different future.

Climate change has transformed the landscape of Nozukile Centane’s lifelong home in Toleni

“I am worried about the future if that dam dries out. It is our source of life. We are dependant on that dam.”

She is a lively woman who laughs easily. On days when she has to collect water, she walks to the Toleni River and carries 20 litres back to her village. Yes, she laughs, she is a strong woman.

Centane does feel the ache of the walk to collect water, but even if the taps stay dry forever she says she will never be able to leave the village. She has called it home her whole life.

“I have nowhere else to go if the water diminishes,” she says.

Her neighbours, two women who have been her lifelong companions, agree.

Unlike Ndumiso’s home near Qwaninga, the water in the taps in Toleni still run. For now.

Ndumiso’s situation will not change until rains heavy enough to fill the Qwaninga River pour from the sky.

Mnyimba knows that the circumstances are dire, but he has no solution yet. For Malope, who sees the suffering of people, the only conceivable answer is rain.

“All we can do is pray,” he says.