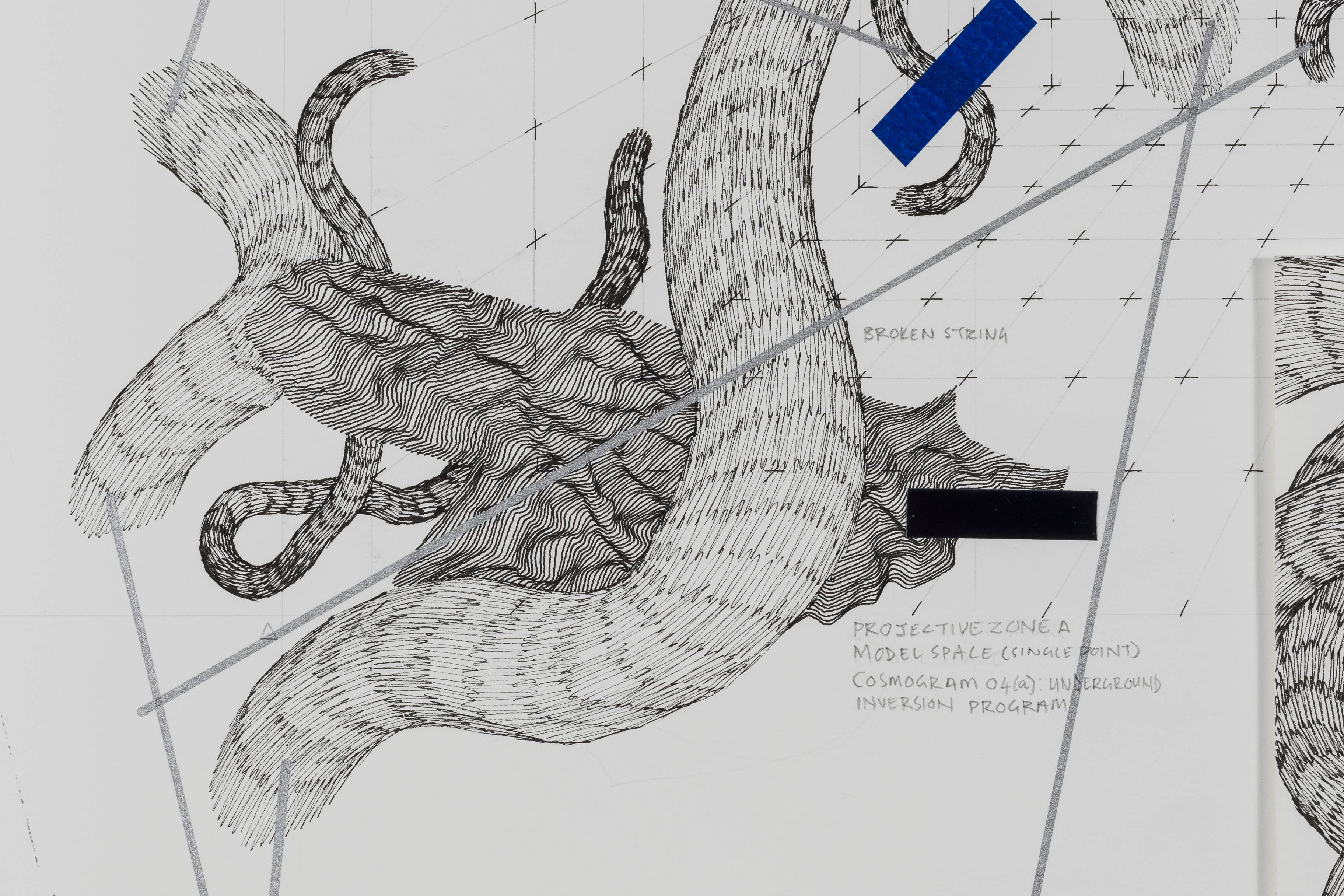

Choices: The Options exhibition is made up of diagrams and schema such as 'prop 8 [prou(k)n]', 2018

In the seminal text by Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire, he argues for learning and teaching as a way to draw closer to a more radical, empathetic humanity.

He posits that oppression is a system of dehumanisation that distorts the humanity of both the oppressor and the oppressed. The oppressed are robbed of their rights, becoming subhuman, whereas the oppressors, in channelling privileges solely to themselves, become superhuman mutants.

“Dehumanisation, which marks not only those whose humanity has been stolen, but also (though in a different way), those who have stolen it, is a distortion of the vocation of becoming more fully human.”

The search for other ways of being and breathing is therefore the search for humanity, a humanity with radical empathy at its core. Or as Steve Bantu Biko put it: “In time, we shall be in a position to bestow on South Africa the greatest possible gift — a more human face.”

Artist Nolan Oswald Dennis is in constant search of this face. The schemata and diagrams that constitute his body of work are sketches of how this could possibly look, how this could possibly be achieved. It is fitting then that his second solo exhibition, showing at the Goodman Gallery in Cape Town, is titled Options.

Options/ Alternatives/ Possibilities/ Choices (the options of origin vs the origins of options).

“The option theory [of decolonisation] is [decolonial scholar Walter] Mignolo’s big thing, decolonial aesthetics,” says Dennis. “The way I make sense of it is through the Zapatistas. They have this declaration that the world that they want is a world in which many worlds can fit. It’s always about black worlds, right?”

The artist and I communicate using WhatsApp. We exchange voice notes, ideas. His voice playing off a cacophony of voices, blaring hooters, taxis screeching past.

“What Options as a concept opens up for me is the possibility of choice. Maybe choice isn’t the right word, but the possibility of difference. Like, if there’s going to be a black world, imagine how many worlds this black world would have to be. I don’t know if this is coming out right, but if there is only one world, then that means that is no world, you know what I mean? And I guess that should also be an option. The option thing for me is not about laying out options, cataloguing the possibilities, but taking the possibility of options as the starting point. Starting from the point that things are already multiple, already complex, already different … So starting from understanding the world as that, as opposed to trying to produce options. It’s also, I guess, a reflection of where I come from. My political consciousness is formed through a world of difference. And not a world of difference in the rainbow nation sense, but a world of black difference. A world where black is as open and as vast as the world presents itself to be.”

Among the sketches in Options is after-world (schema), 2018. Nolan Oswald Dennis.

A recurring motif in the work of Dennis is an entanglement of disembodied human figures, disjointed at every limb. Arm from arm on arm. A mass of bodies forming one body. A new face in which many faces can fit. In after-world (schema), 2018, produced for Options, the mass of humanness, this complication of the corporeal, appears twice, held in place by fleshy tubes mirrored by each corner of the diagram. The diagrams, however, seem to dismiss the sense of authority that most diagrams seem to have. These diagrams feel like suggestions, like prompts.

I ask the artist about the sketchwork, and the denial of assuredness.

“It’s not so much a strategy to erase or deflect or have some kind of partial relationship. For me more a kind of fertile orientation of the world, this notion of composition and decomposition. To grow. To return. There’s this impermanence that we have to grapple with at some point. The work is never done, so why should the work front like it’s done. We’re picking up the work of our ancestors, and we do it, but it’s never done. In my practice, these things that come out of it, the drawings, the systems, the diagrams, the objects, they don’t have to front as if they’re finished. They are just a reflection of what they are. And what they are is a working through that is never-ending.”

The work is never-ending. This is the true inheritance of the meek. A struggle that precedes us, that precedes those before us. Armed to the arms, to the teeth. Arm in arm against and with each other. A struggle in which many struggles can fit.

“What I like about diagrams as drawings is the sense of tension. In architecture, an architect spends all his time making the drawing. But the drawing isn’t the work; the building is the work; or a painter who produces sketches, but the sketches aren’t the work, the painting is the work. Drawings have a role to play as the kind of work that is never meant to be the ultimate work. There’s something contingent. There’s something rough. Even the most precise architectural drawing is still a concept drawing. It’s a way to relate. The world is not done. It’s not me that changes my mind; it’s the world that changes and I have to adjust. And the work has to be open to adjust.”

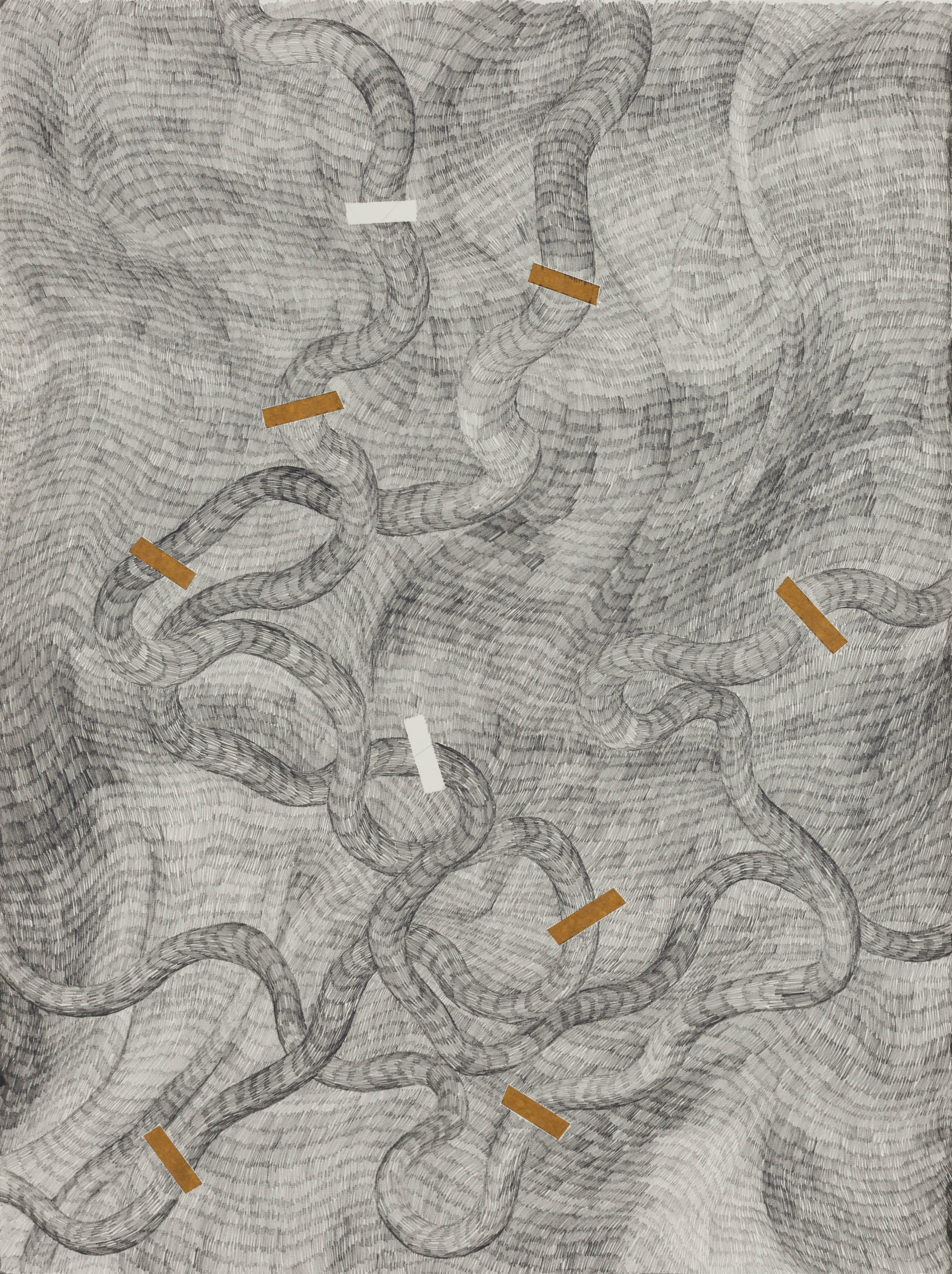

Intestines/ worms/ tissue/ matter/ wormholes/ wounds/ “some internal biological opening”.

They are hard to miss. Large tubular entanglements that worm their way through the work as though to devour it, to leave it gaping and incomplete. In some pieces, the holes are all there is. And what is lack without abundance to contrast it? A series of holes, of something missing, absence as solid as presence.

“I don’t think it’s the wrong direction to go intestinal,” he expands. “Of course earthworms are very close to my practice right now. Internal bodily structures. Earthworms to me are an internal community, internal to the land. There’s a similar language between the earthworms and the intestines because they are kind of dealing with similar things. I think what attracts me to them is that they deal with this kind of underneath. Under the skin. Inside the body. Under the ground. Something about what emerges when you dig.

Alternatives: prop10 [prou(k)n], 2018 from Options. Nolan Oswald Dennis’s artworks in the exhibition, on at the Goodman Gallery in Cape Town, is a search for humanity as opposed to oppression that makes people subhuman.

“There’s also a language of roots, the branching structures of roots. And digesting. And worms, part of the reason their bodies look that way is that they are primarily one digestion system. They’re like a travelling gut that’s digesting the earth, and it’s a beautiful thing. But also [they are] a gesture I’m interested in. How we can, or I can, start to think about bodies in a different way. And bodies that can be absorbed or imbibed. Bringing things inside. Or occupying things from the inside.”

Dennis recently completed his master’s of science in art, culture and technology from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). For his final project, he harvested a colony of worms, keeping them alive by feeding them text.

“My MIT project was kind of straightforward. I was confronted with the overwhelming access to information about, supposedly about myself. The archive of colonial, ethnographic, sociological and contemporary research about the other. Us. Me. Black people. Africans. And I spent a lot of time in the libraries: Harvard, Yale, MIT. After a while it feels a bit redundant. What do you do with all this information? At first I thought that if I can work through it I can understand something. I can gain some information. I started to think about what else can be done with all this text, this information, this physical weight of all these millions of books. That drew me to worms who eat the cellulose of plants and the pages of books are made out of cellulose. Actually a lot books are coated in chemicals to stop insects from eating them. So I thought of how to decompose these texts. And worms are the essential community you’re going to have to deal with to talk about decomposition, or thinking about returning to the land. Or returning all this data to the planetary body.”

He would begin the process by washing the books, to clean any chemicals off of them. And then he would feed the books to his underworld of “travelling guts”. The worms would eat the cellulose and this process of digestion would produce three things: excess energy in the form of heat, compost and more worms through reproduction. And the worms that eat the cellulose, living off pages, now find themselves documented on paper, from cellulose to cellulose. Dust to dust.

“There’s nothing linear about what it means. The idea of entanglement is super-important because all of these works are searching for something. And the search is leading me to the space of these tubular entanglements. It follows a lot of underground, hidden infrastructures. If you think of sewer lines, or piping, or electricity lines. Tubes. The worm system. The root system. Our veins. Our guts. The way our brains are this kind of condensed entanglement of neural tissue.”

But there is something grotesque about making the unseen seen. Although we understand and acknowledge the subsystems that support our chosen and imposed ways of living and breathing, rarely do we want to see the viscera, the entrails. Rarely do we want to acknowledge, with our bodies, the way things actually work. It’s easier to know the man and systems than to actually view how the systems work, lest we find ourselves in there, working against ourselves. In his diagrams, there are blank labels, which feel almost like a dare from the artist. Do you see yourself in this system? Do you see how you fit here?

“I kind of think this is the critical thing. If you think about options, or things being partial, or somewhat incomplete but not as a gesture, just as the nature of things, there’s always this necessity for space. And how do you produce space? And when you think about the language of diagrams, it tries to be so complete. There’s confidence in a diagram. It presents itself as if it’s true. My thing about diagrams is to think about how the language of truth or respectability or rationality can be used to reach an extra rationale. Can be used to reach something that is outside of the system. The gaps are basically that.”

Option runs at the Goodman Gallery Cape Town until March 9