Storyteller: Bahiyya Khan resists stereotypes of Muslim girls and has used her skills to create a video game about a fictional character called Lilith Grey who has borderline personality disorder. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

I saw Bahiyya Khan for the first time in 2015. I had just finished my dhuhr prayers at the mosque facility for students on the University of the Witwatersrand’s main campus, and I wondered who this pink-haired girl preparing to offer her prayers was.

“A lot of people get shocked when I tell them that I’m Muslim,” Khan tells me as we sit cross-legged on the floor in a passage at the Wits School of Arts. “I wear a scarf on my head on Fridays and someone once asked me if I converted to Islam. It pissed me off so much. Muslims don’t have ‘a look’. This whole ‘brown skin, turbans, beard and scarf thing’ is a stereotype that the West invented.”

A Lenasia native, Khan is comfortable with doing her own thing. That’s how she stumbled into game design, where she’s been causing waves with her game, after HOURS. She’s headed to San Francisco to attend the Game Developers Conference on March 15, where after HOURS has been nominated for the best student game at the conference’s Independent Games Festival, one of six shortlisted for the final award. It took Khan only 12 hours to crowdfund the R45 000 she needed to get herself to the conference. “I don’t have any money. Everyone was nice and helped me. I don’t even know most of them,” she says.

A vignette full-motion video game — a narration technique that relies on pre-recorded video files to display action in the game — after HOURS explores the life of Lilith Grey. The fictional Grey lives with borderline personality disorder (BPD) after being molested as a child. Through the character of Grey, Khan uses a unique form of storytelling to relay what life is like for young women who have survived sexual abuse and who live with mental illness. “I like to make games because it’s a cool medium of storytelling, and the most active way to consume a story. And I like film more than I like games, which is why I use film in my games,” says Khan. The premise of the game is based on a series of true stories about women she knows who have been raped. Khan says she wanted to show Grey as a soft, vulnerable person — a complex and multifaceted human being, who is interested in poetry and rock bands.

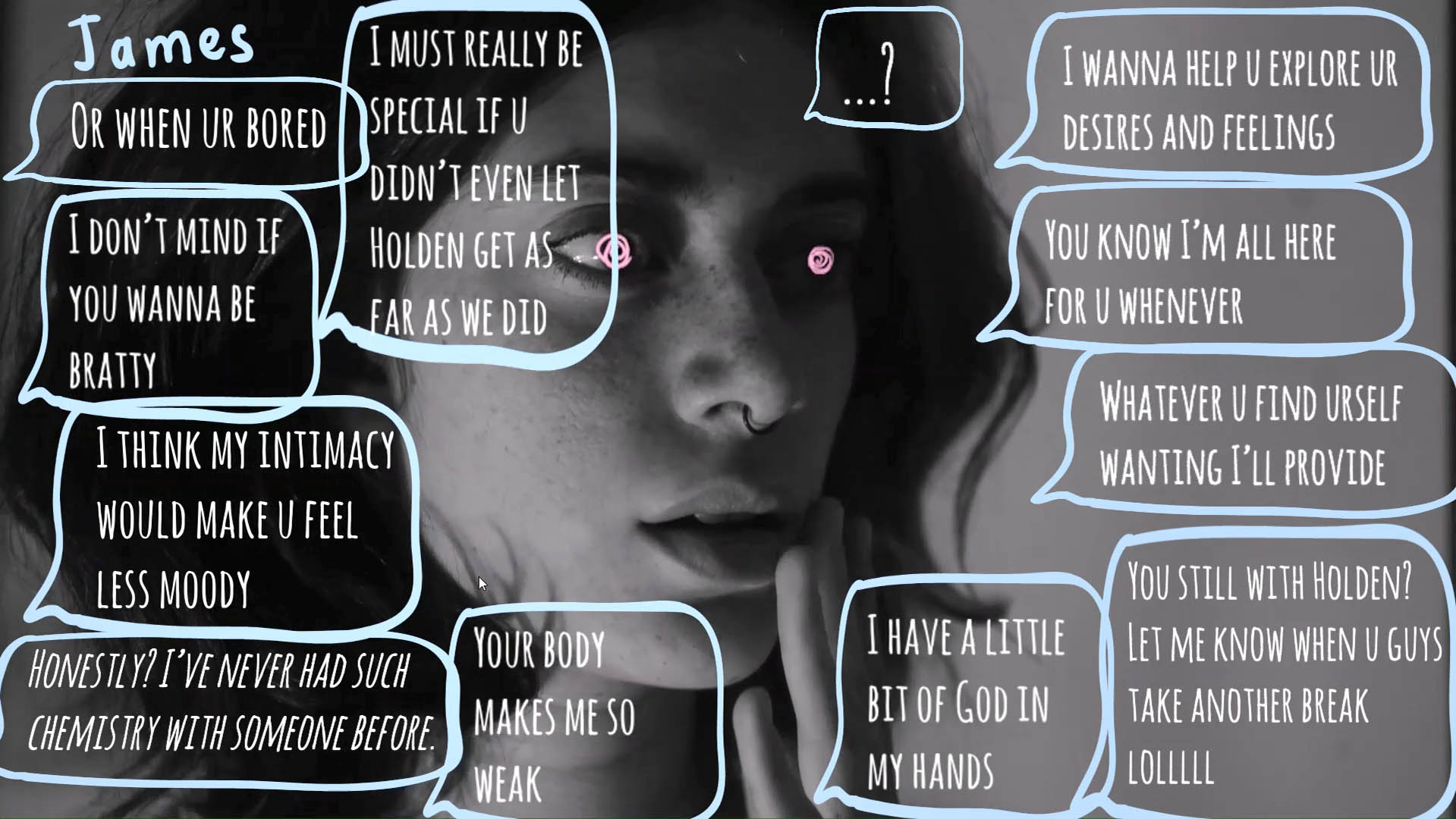

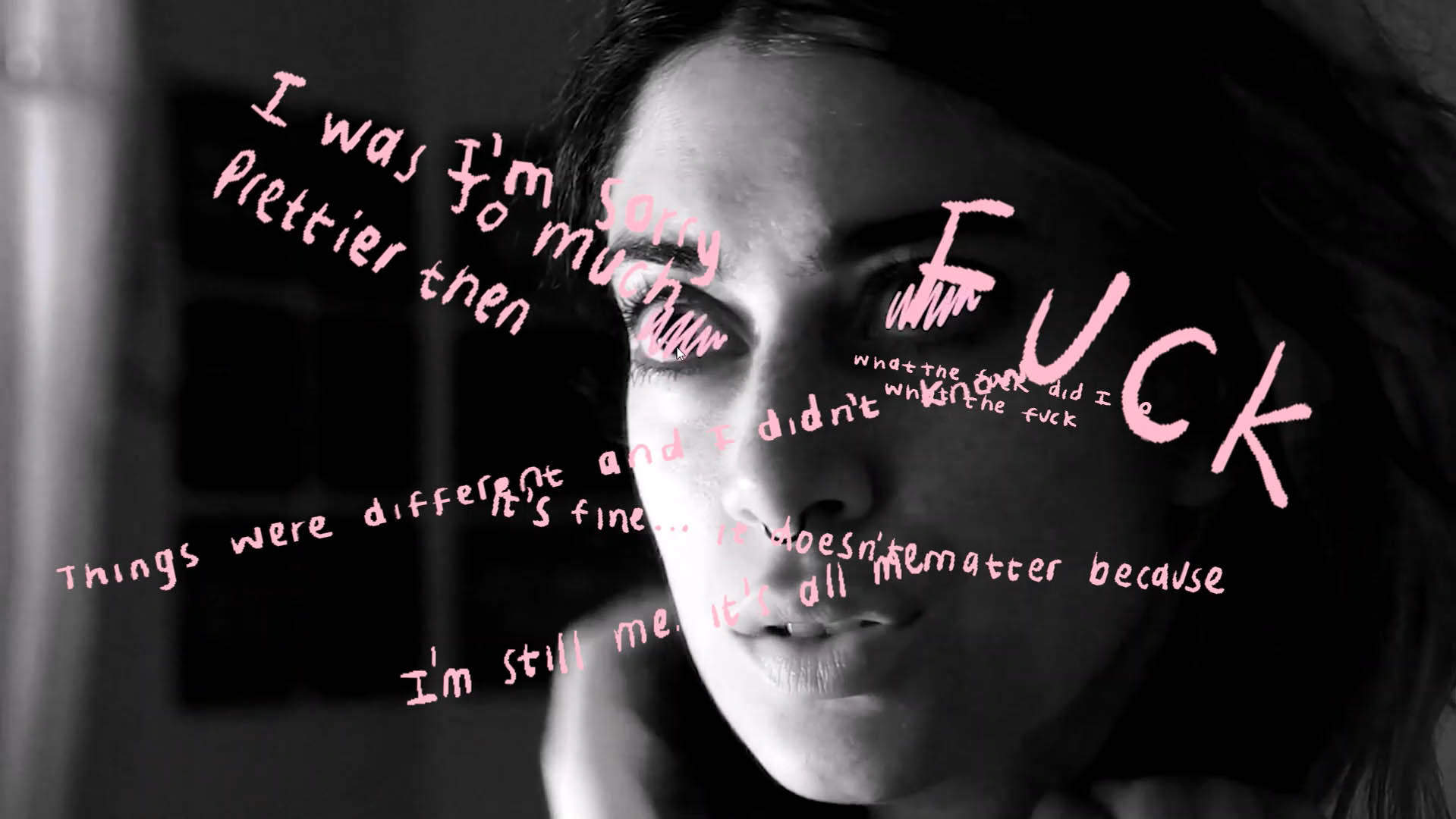

Playing the game, you spend a night with Grey. You read her diary, have conversations with her and navigate her responses to triggers with clickable options to scream or cry. When she gets texts, you choose her replies to them. As a player, you are displaced; despite making Grey’s decisions, you can only make them insofar as she allows you to. It’s these tiny idiosyncrasies that lend insight into the ways that Grey’s mind works, revealing the deep-seated ways in which trauma and mental illness operate. The simple visuals, shot in monochrome with handwritten pink and blue text, belie the complexity of the game.

Khan was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder when she was 19. In 2017, she began to research how the disorder was reported on in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and was horrified by the way borderline personality disorder was spoken about. “I didn’t want that to be the main narrative of BPD. Especially coming from a brown community, people don’t talk about mental illness enough or it gets ascribed as a white people thing, which is bullshit because then brown girls think they’re crazy for being ill. People make you hate yourself on top of you already hating yourself for whatever reason. Do they think we want to be like this? And that’s how after HOURS came about.”

Reality: Screengrabs (above and below) of after HOURS reflect the issues that the game confronts and discusses

Khan’s success with after HOURS has taken her around the world. Initially her honours project, she submitted the game to A MAZE, a games festival held in Johannesburg, where it won the Pinkest Game award. A MAZE founder Thorsten Wiedemann describes pink games as those that are weird, thought-provoking games and playful, using the colour as a descriptor because, for him, it means “interactivity, confrontation and positive chaos”.

Her prize included a trip to A MAZE Berlin in 2018, where she won the best new talent award and got a deal for the game to be published by Humble Bundle, a renowned video game digital distribution company. Not bad for a girl who didn’t have a cellphone until she was 19 — when she got her first phone at 14, it was confiscated soon after by her unimpressed mother because older boys would call her late at night.

But her success has been hard-won. When she first got to Wits in 2014, she struggled. “First year was one of the worst years of my life. It was so white. There were so many cultural barriers. I came from a school where my fees were maximum R2 000 a year,” she says. Khan was exposed to tools like Microsoft Word for the first time at Wits, where she was one of only 15 students in her game design degree. She found her peers insufferable. “I used to be so smart in high school, then I came here and I would get like 54%. And I was so put off gaming culture because of all the white boys in my class. Everyone made it that you had to be into anime and comics and wear Star Wars T-shirts — I don’t give a shit about that stuff.”

She wanted to switch to studying film instead, which all her friends were doing. But she couldn’t deal with the thought of going back a year academically when her fees were setting her parents back R55 000 annually.

Then, in 2015, her second year, her stepfather was murdered. “I went fucked in my head when that happened. I was just crying all the time. I missed out on so much work.”

Game design is not a conventional career choice for women from Khan’s background. Her three older sisters studied science, psychology and teaching, and her mother wanted her to do accounting. She applied for law and for mechanical engineering as safe options alongside game design — but when she got in, she went for it. Convention, after all, has never been her cup of tea. “I can’t be forced into things. I know so many girls from school who’ve just fallen into marriage, and they aren’t even fucken in love with their husbands. It finishes me. Marriage is not this big thing that will complete me. I’ll complete me.”

Khan’s religious beliefs keep her grounded. “For me, being a good human being is synonymous with being a good Muslim. And I feel like Islam is a way for me to keep myself in check. My mother always reminds me to make sure I don’t do things that would displease Allah. Even for this nomination, my mother told me to pray that I win only if winning will be good for me, and not if I become arrogant because of it. Being a Muslim is just about being nice.”

Last year Khan began her master’s in digital arts with a focus on experimental storytelling, but was forced to put it on hold because of lack of funding. For now, though, she is pouring herself into her games, and the ways they act as a medium to connect people. “I really like telling stories, especially my people’s stories. The people I care about the most are the ones I identify with the most — Muslims, mixed-race people, women, depressed people, people from shitty areas, hustlers — I’ve been hustling since I was 14 and lying about my age so I could work.” Some of the backstories in other games Khan has developed feature themes such as the legacy of apartheid and Palestinian activism.

Before she left Lenasia Secondary School, one of Khan’s teachers told her not to worry about high school — that when she got to university, she’d realise that the whole world is not “fucken Lenz”.

And through her games, she’s had the opportunity to see that.