Out loud: Fiona Snyckers revisits the well-known novel 'Disgrace' by JM Coetzee and gives one of his main characters a different view in her latest book, 'Lacuna'. Photos: Paul Botes

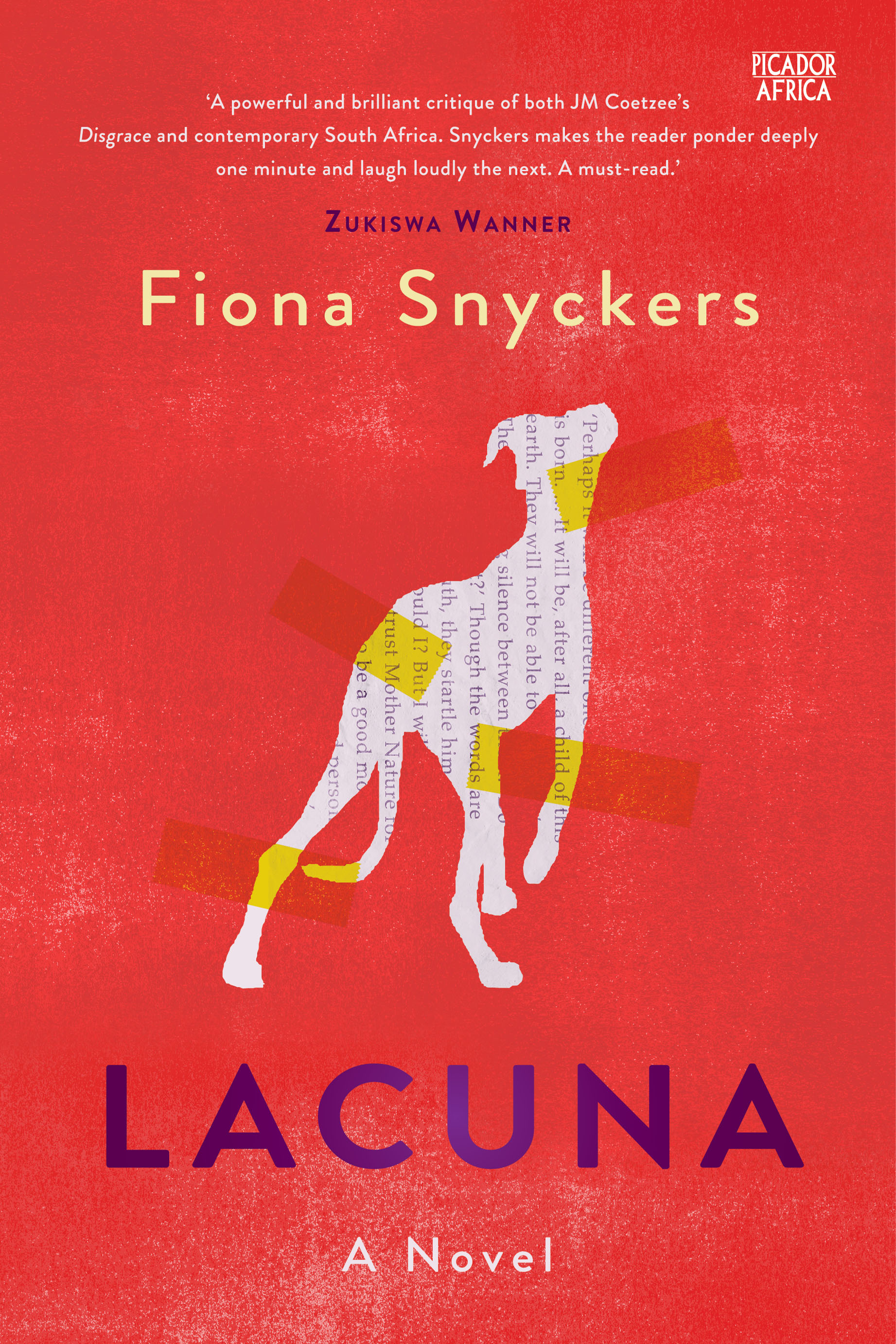

LACUNA by Fiona Snyckers

(Picador Africa)

Literary fiction is, to its worshippers and faithful, opium not easily found in the drudgery of other fictions concerned with lesser passions and peripheral amusements. This is a dangerous statement because literary fiction courts danger, it invites high praise or ridicule, often births profound readings and imagination of life and existence. There is some snobbery, sure, but this is because prime seats in the realm of higher fiction are an all-or-nothing war for both writers and readers.

The standards by which literary fiction is judged can be unforgiving, for the precise reason that there are grand expectations for those gifted or insane enough to dabble in the explosive trenches of thinking and writing work which, in its nature and essence, is meant to be unsettling, polarising, cosmic in range and bravery, groundbreaking as much as it is complex, but accessible. This demands some creative and intellectual tap dancing; informed stunts on the slippery floors of authorship and gravitas in the illuminating or brutal shrines of literary reviews and criticism.

Enter Fiona Snyckers with Lacuna, a novel steeped in the partial, textual world of JM Coetzee’s Booker prize-winning novel, Disgrace. Snyckers’s novel engages and disengages Disgrace at character (an extension and re-imagination of Lucy Lurie) and selective thematic interfaces — predominantly the rape of a white woman by black men. The central premise driving Lacuna’s narrative is a diametric comparison between Disgrace’s Lucy (dubbed Fiction Lucy by Snyckers), rendered to take certain “passive” and philosophical positions regarding her rape and the Lacuna Lucy, who is in the throes of post-traumatic stress and active rebellion against her rape. The passive Lucy versus rebellious Lucy forms the central tensions between the two books.

This interplay is further complicated by Snyckers’s creative distortions of known and publicly confirmed biographical details of Coetzee, who is recast as a fictional writer-academic.

Simply named John Coetzee in Lacuna, the dropping of the qualifying “M” creates some complex dualities — a sharpening and dimming of the cultural significance of Disgrace the novel and the high-voltage (re)-invention of a writer named John Coetzee, who wrote only Disgrace.

This is a historical distortion that creates reference distance and creative liberties for Snyckers’s Lacuna world. The complexity of Lacuna resides, in part, in the fact that the book cross-pollinates South African history with the unreliable literary biography and celebrity of JM Coetzee; touches on meta fiction without being hamstrung by it; and takes certain tough erasures of whole worlds of Coetzee’s Disgrace to focus on and ventilate issues supposedly “omitted” in JM Coetzee’s text.

David Lurie — the principal trigger and moral mirror of Disgrace — has lost his romantic poetry passions and sexual prowess, for instance, and is recast as an insurance claim fraudster. Snyckers riskily but capably relies on the fame and critical acclaim of Disgrace to orchestrate the Lacuna world in critical co-existence and reinventions.

A thin, but real, membrane separates the worlds of the Coetzee-Snyckers books, for the logical reason that intertextuality is impossible without intertextual mirroring. In other words, no Lacuna without Disgrace, and no Lucy Lurie or Fiction Lucy without the original Coetzee Lucy template. But this would be a lazy, minimalist and reductionist reading of Lacuna, for literature is supposed to be much more versatile than compartmentalised analysis. It is, rather, important to, not without critical engagement or judgment, submit to the Lacuna world — bearing in mind that intertextuality does not dismiss or negate that the mode and apparatus at play are those of fiction and invention.

Snyckers’s writing (prose, dialogue) is pitch perfect, wise, charged and revelatory, offering a dazzling reading of history, literature, psychology, academia, trauma, race and gender relations and the concept and practical implications of criminal and personal justice. The text is, at face value, overwritten in parts, coming across as somewhat preachy — particularly in areas concerning social commentary on present-day South Africa; more specifically, the exploration of white privilege versus black exploitation and dispossession. This is not enough to ruin the overall achievements of the novel, however (a slight irritation at best), for the characterisation is penetrative and memorable, including Lucy’s brisk friend Moira, her judgmental psychologist Lydia Bascombe, her online dating site love interest Eugene Huzain and his cousin Raz, as well as the real and imagined academic and celebrity writer John Coetzee.

In full flight, Snyckers’s prose burns like embers in the exposition and scrutiny of rape and its aftermath; soars like an eagle in its articulation of the personal versus the societal.

Lacuna is not a perfect novel — there is none — but it is, for the risks it takes and for clarity of its moral urgency, a brilliant book whether or not read in the shadow of Coetzee’s original.

It is, also, not a claustrophobic and one-dimensional book about rape. Snyckers still manages to infuse bewitching humour into the novel’s macabre preoccupations — to explore light-hearted, beautiful things such as love and romance, sensuality and sexuality, friendship and the resilience and splendour of the human spirit.

Minor faults aside, Lacuna is a brave and luminous book, an important addition to the purpose and growth of comparative literatures.

The opium effect is a welcome one: erasure and the filling of the narrative gaps in dominant fiction that dare inquiry and unsettle revision of significant texts in the South African literary canon — to the celebration or ire of varying literary constituents — and reality checks of cracks in our fragile social cohesion and nationhood projects.

A necessary contradiction is that it is important, in untangling and deciphering meanings coded in literary texts, not to confuse the posturing and fables of genre (for instance, literary fiction) with the grand omnipotence of art. It is worth remembering that literary fiction is but a branch of literature and, as such, prone to typical and/or atypical readings. As a work of art and not a cherry of genre, Lacuna is neither typical nor atypical; it is abundant, which is to say a wealth of numbing and contagious truths fill its veins. The contagion is what propels and distinguishes artistic and metaphoric hydrogen bombs from mediocre genre pyrotechnics.

In a sense, the full power and significance of the novel does not belong to immediate reflection and criticism, but poses far-reaching postulations as to the purpose and full manifestation of evolving intertextuality as a narrative anchor and intellectual canvas. In both instances, the anchor and canvas have implications for subsequent cross-pollination of stories — particularly the relationship and conversations between new literature and iconic and famous texts such as Disgrace (Coetzee), Lolita (Nabokov), Hunger (Hamsun) or Black Sunlight (Marechera).

An interesting phenomenon emerges, that of writing towards and away from established literary canons, wherein the act of creation of new literature moves forward through a historic cultural lens. Three issues emanate from that realm of creative outlook. First is the exploration of famous texts in the context of literary celebrity; second is the rethinking, rewriting and re-fictionalisation of such texts by means of narrative recasting and appropriations; and third, the juggling of double consciousness between the original text and its competitive or complementary sister text.

The (informed, purposeful) snobbery of literary fiction is perhaps the very quality measure that ushers discreet demands on writers and their reading public to strive for a higher intelligence and understanding of texts and events around them in past and present cultural times, to hold contradictory opinions of high praise and selected disagreements at the same time, to stretch emotive and intellectual comfort zones to breaking point with a view to reconstruct, and in some cases, elevate the registers of artistic consciousness and the addition of important texts to the sensitive and sacred iconography of heritage.

It is evident that Snyckers is well versed with the public life and limitations of texts and, as such, has navigated the almost invisible line between intelligent fiction and thematic timelessness. Her greatest achievement, or perhaps understated talent, is how her authorial instincts handle gradients of emotion, such that reading becomes a very complicit and sensory affair.

Overall, Lacuna is a great teacher and prism of human imperfections and triumphs and, as such, not a book to be read at pompous malls or picnics.

Nthikeng Mohlele recently authored Michael K: A Novel (Picador Africa), a literary response to JM Coetzee’s Life and Times of Michael K (Ravan Press)