The documentary Leaving Neverland has audiences split on whether the latest revelations about his alleged sexual abuse of two boys are valid or a public lynching of a successful black figure. (Dave Hogan/Getty Images)

Michael Jackson speaks to and for the monstrous child in us all — Margo Jefferson, On Michael Jackson (Granta Books)

We cling to [Muhammad Ali] because he reminds us — in this cold-hearted, cynical age — that there’s still virtue in devoting our lives to causes larger than ourselves — Nathan McCall, On Redemption, What’s Going On (Vintage Books)

It’s storming babies and piglets outside my window. Stuff Scooby-Doo, my children, gap-toothed “Little Miss Sunshine” Liyema-Touré, and the resident revolutionary Cuba and I are sardined in the bedroom, prostrated at the feet of the queen who was once the king.

The royalty in question is Michael Jackson and the seance we are participating in is a ritual performance of Michael Jackson music beamed through endless loops, song after song.

Don’t ever call him MJ. He is not your friend, he is mine. The boy is mine. And now my children’s.

His wiry body — once a black boy’s body and now definitely Diana Ross’s borrowed body — a jazz cat’s and toy-land Mafioso attire, remixing Fred Astaire, Bob Fosse, Gene Kelly, Sammy Davis Jr and James Brown in half-seconds of magical spasms and gravity-defying Dogon dance moves. His pale, white face and beaky lips, what one comedian once said is his “outer/inner Elizabeth Taylor” after getting rid of his inner black bitch or butch Dirty Diana, frame after frame, ooohs, eeews, aaahs, punctuating his songs.

Rapt and tearful with glee and wonder, the children refuse to pick up their little jaws from the floor. Although starving, they also refuse to fetch their food from the kitchen. Aged eight and four years old, born two and six years after their daddy’s childhood god-figurine died, their adoration for Michael Jackson is stubborn and reeks of a devotion that belies their understanding of life. Weirdly, I’m just as transfixed.

Meanwhile, the new HBO documentary, Leaving Neverland, a harrowing testimony, is dividing millions of fans globally. It is also eating at the souls of black folk globally.

Directed by the British filmmaker Dan Reed, Leaving Neverland focuses on two white men, known fame-seeker James Safechuck and would-be choreographer Wade Robson, who allege that Jackson abused them in their childhood, unbeknown to their parents.

Abuse is too amorphous. They claim Michael Jackson raped them. Premiering at the Sundance Film Festival in January, the two-part documentary portended hell for Michael Jackson fans and some kind of end-of-the-world, end-of-morality double dance for humanity from the get-go.

The biggest fallout resulting from Leaving Neverland is that radio stations, particularly in the United Kingdom, United States, Canada and New Zealand, are deleting Jackson from their playlists, creating a paradox never experienced in popular culture before.

The more media houses take this harsh stance, the more fans clamour for his music.

According to the Evening Standard: “Jackson’s Number Ones album charted at number 43 after climbing 44 places on the rung, while The Essential Michael Jackson climbed to number 79.”

The singles Bad and Thriller also climbed to 142 and 147, respectively. Meantime, in the US, the powers behind the popular cartoon series The Simpsons decided to take an episode featuring Michael Jackson off air.

Amid all that, the performer’s family has called out the documentary as “public lynching”, clearly evoking images of slavery and the Jim Crow era in which subversive and run-away black folk were hanged and beaten up in public.

But activists will have none of this. Several musicians such as hip-hop star Drake have dropped posthumous remixes and musical collaborations from their live repertoire. The Pulitzer-winning dance critic, Margo Jefferson, who penned the rather insightful slim volume On Michael Jackson, a letter to the boy-child wonder-cum-pop “monster”, says she now wishes she knew better about the abuse allegations when she worked on her monograph.

In London fans are hitting back, with graffiti hewing close to the “public lynching” narrative.

I have been a Michael Jackson fan since I learnt to walk. His music has served as a soundtrack to my life from the days he was in The Jackson Five. You won’t understand it. Michael Jackson’s art served as much more than the soundtrack to my life.

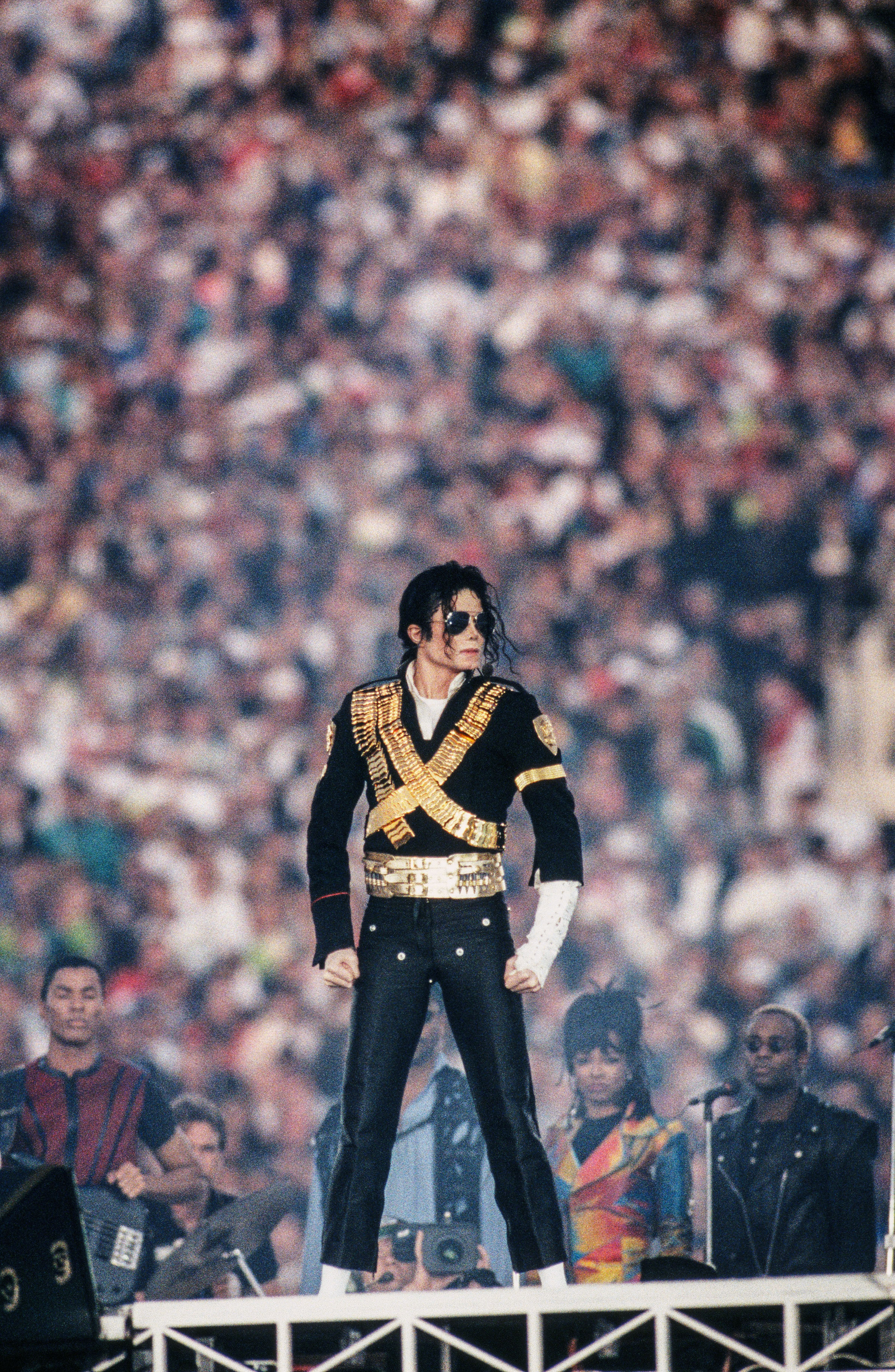

(Getty Images)

As with Brenda Fassie, Joy, Donna Summer, Sylvester and later Miriam Makeba, Michael Jackson’s performance art raised me. It wiped tears off my face and bathed me.

It did so much more.

To me and my acne-ridden mates, nappy-haired, watching our mothers dance to his music (and, in more cases than gender activists would love to admit, both parents) black and wretched, black and beautiful, that he, like God, who might have looked like the ever-transmorgrifying face of Michael, or the bearded white man with blue eyes from European portraiture in my grandfather’s church, loved us too — against all evidence.

Michael offered us succour.

Don’t ever call him Michael, he is mine.

Yours, too?

Mhhh. A star-child from Gary, Indiana, Michael Jackson telegraphed a simple but much-needed message: it’s all right to be black and ambitious. It is also all right for an ebony child to dream of escaping the places we knew as home. His art taught us that we, too, mattered.

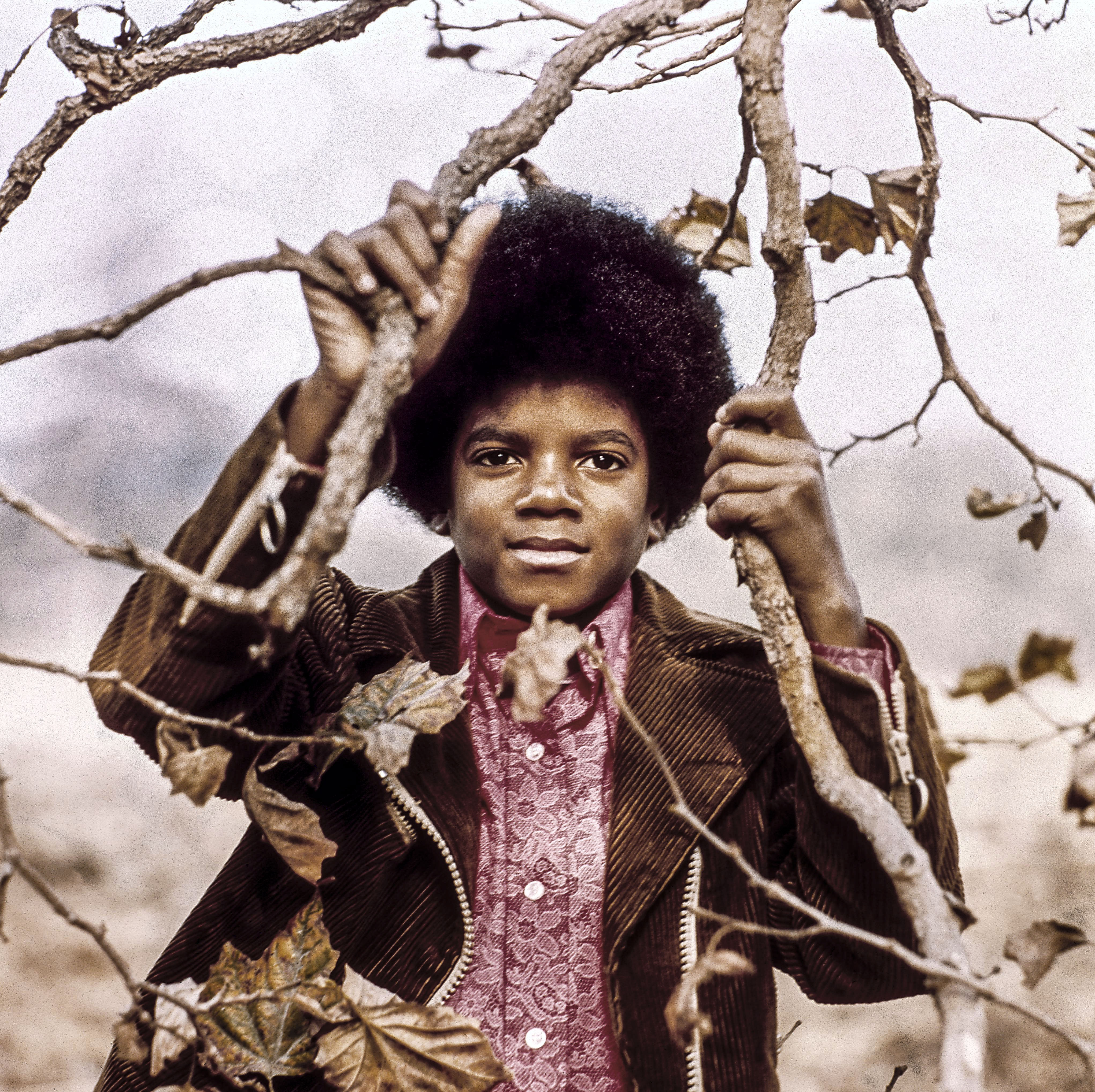

Innocence lost: The young Michael Jackson (above) and the well-known performer he grew up to be (below). (RB/Redferns and Carlo Allegri/Getty Images)

The irony is that the whiter he became, the more desperate we, or at least I, pined for him to come back home.

I have been a music, culture and social critic for more than a quarter-century. I am also a parent raising children in a society that is harrowingly unkind, feeds off, enslaves, rapes and trafficks children.

So where am I in this?

Not to mince words, I am for Michael Jackson the artist. After an excruciating process of introspection, I have decided I will never burn his LPs, will never crush his CDs, will never dump his DVDs in the bin of history nor feed his books to the shredder. No I won’t. Let the chips fall where they should.

Perhaps we need greater debate about the place of art and the artist in society, since a great deal of art issues out of deeply depraved spaces and is created by deeply abhorrent souls.

Yes, it does feel indulgent, insensitive even, to survivors, whom we label victims, thus double-victimising them, to continue supporting their abusers’ art. And yet if we are to burn, ban or take off all art created by the terrible men of this world — yes, they are mostly men — going back millennia, there would not be documentary proof of culture’s footprints, and we would be devoid of any history, even complicated history. The archives will be barren, and we will be projecting a new moral Nazism on art.

We should then implode all modern-day buildings created by evil architects, reject most of technology innovated by the creeps and abusive men of Silicon Valley, and just live lives constructed around the new dictates of fundamentalism masquerading as activism.

What should we do with this?

First, we need to explore what we mean by this: Is it the artist’s art or character we are dealing with? Are the two indivisible?

Have millions of fans stopped listening to Marvin Gaye because he left his wife to marry teenager Janis Hunter?

Have we stopped enriching the already filthy-rich The Rolling Stones after all the stories we know of their ruthless sexcapades with teenagers — to be clear, minors — as they criss-crossed the US promoting albums such as Beggars Banquet and Exile On Main St?

Just three years ago, the “father of rock ’n roll” Chuck Berry was restored to the top of the rock pantheon after he died, despite multiple sex scandals in his lifetime.

Although the name Michael Jackson and the word abuse are not strangers in the popular imagination, most of us, at least those who care about popular culture and its effect on society, began to regard him with both nostalgic ambivalence and relief

Michael Jackson and children attend “Dangerous” Tour Press Conference on February 14, 1992 at Radio City Music Hall in New York City. (Photo by Ron Galella/ Wire Image)

Ambivalence, because we told ourselves he is the problematic icon, the eccentric child-uncle every family has. Relief, because the spectre of seeing our childhood hero falling from the ultimate cultural peak and rotting for the rest of his life in jail was depressing.

No matter that the peak we are herein extolling is also partly manufactured idolatry, part of the billion-dollar star-making machine. So, yes, for years, at least the last 20 years, Michael Jackson occupied that uneasy space in my soul and, dare I say, in the souls of black folk worldwide.

I’m intentionally shining a light on the parallel between his two modes of popularity: overall popularity on one hand and psychic appeal to people of African descent worldwide on the other. It is a race thing. Michael Jackson is a race thing. Everything about him, from the skin and features alterations to the fluidity of the music genre, his own heroes, the business around him, the multi-racialism but, as per Marvin Gaye, “divided souls”, singular cultural signifiers of his vast crossover fan base.

In denial, embrace, self-transformation, daring and retreat, Michael Jackson, much more than other icons such as Muhammad Ali, brought race and its “isms” to our daily existence in ways uncomfortable, complex and complicated. Thus, it is impossible to unthink and spool race out of any discussion on him.

What, then, do I do with this dilemma? What should I tell the children? Are they too young for full-on feminist or plain activist rhetoric? Should I maybe talk down to them, teach them about the dangers of accepting sweets from strangers? They already know that. Should my wife and I teach them that men are monsters, the language they understand from watching cartoons? Monsters and princesses. Should we tell them that black men will defile them, make them spread their bum cheeks or deposit salty, slimy liquid in their little mouths and tell them they love them? Does that mean white men and everyone else are, as Liyema-Touré would ask: “All angels, daddy?” What kind of fuckery would that be?

Or should I, like the American parents who left their children in Michael Jackson’s care, neglect my duties and maybe sneak in the line that the performer we are now watching is a monster with a capital “M”? But it’s all right, he is dead now. He will do you no harm and if he dares to, Black Panther’s King T’Challa will kick his ass.

I will never be a willing party to abuse. I also understand what writer Pearl Cleage meant in her book Mad at Miles, about one of our beautiful and cruel objects of desire and black pride, Miles Davis, who confessed to slapping up women in his self-titled autobiography.

She wrote: “Scratching up his CDs and burning his cassettes sounds scary, right? But what are we going to do? Either we think our brothers have to take responsibility for stopping the war against us, or we don’t. And if we do, should we have kept giving our money to Miles Davis so that he could buy another Malibu Beach house and terrorise our sisters in it?”

Cleage asked: “Can we make love to the rhythms of ‘early Miles’ when he may have spent the morning of the day he recorded the music slapping one of our sisters in the mouth? Let that sink in.”

Ditto, Michael Jackson. There is no way of getting around it. What we don’t know, though, and what the obsessive American legal system has not yet proved, is whether Michael Jackson actually raped those boys, and here is the clue that we don’t. The rule of thumb is, of course, to believe the victim. Are James Safechuck and Wade Robson worthy of our trust? Why did they wait for 10 years, when Michael Jackson could not speak for himself?

As for our heroes, the question is: How can they hit us and still be our heroes — our leaders, our husbands, our heroes, our lovers, our friends, our geniuses? And the answer is: They can’t, can they?

As for me, I surely have that life task to teach my children about compassion, the complications of love, how to notice that blurry line between love and adoration, between devotion and obsession.

These, too, are lessons I’m aware I will have to relearn myself as we negotiate the labyrinthine web called “growing up” with radical care.

Telegram to self: Yo, I’m committed to teaching my children.

Go raise yours.

Do you, boo.

Bongani Madondo is the author and editor of I’m Not Your Weekend Special: Portraits on the Life, Style & Politics of Brenda Fassie (Picador Africa)