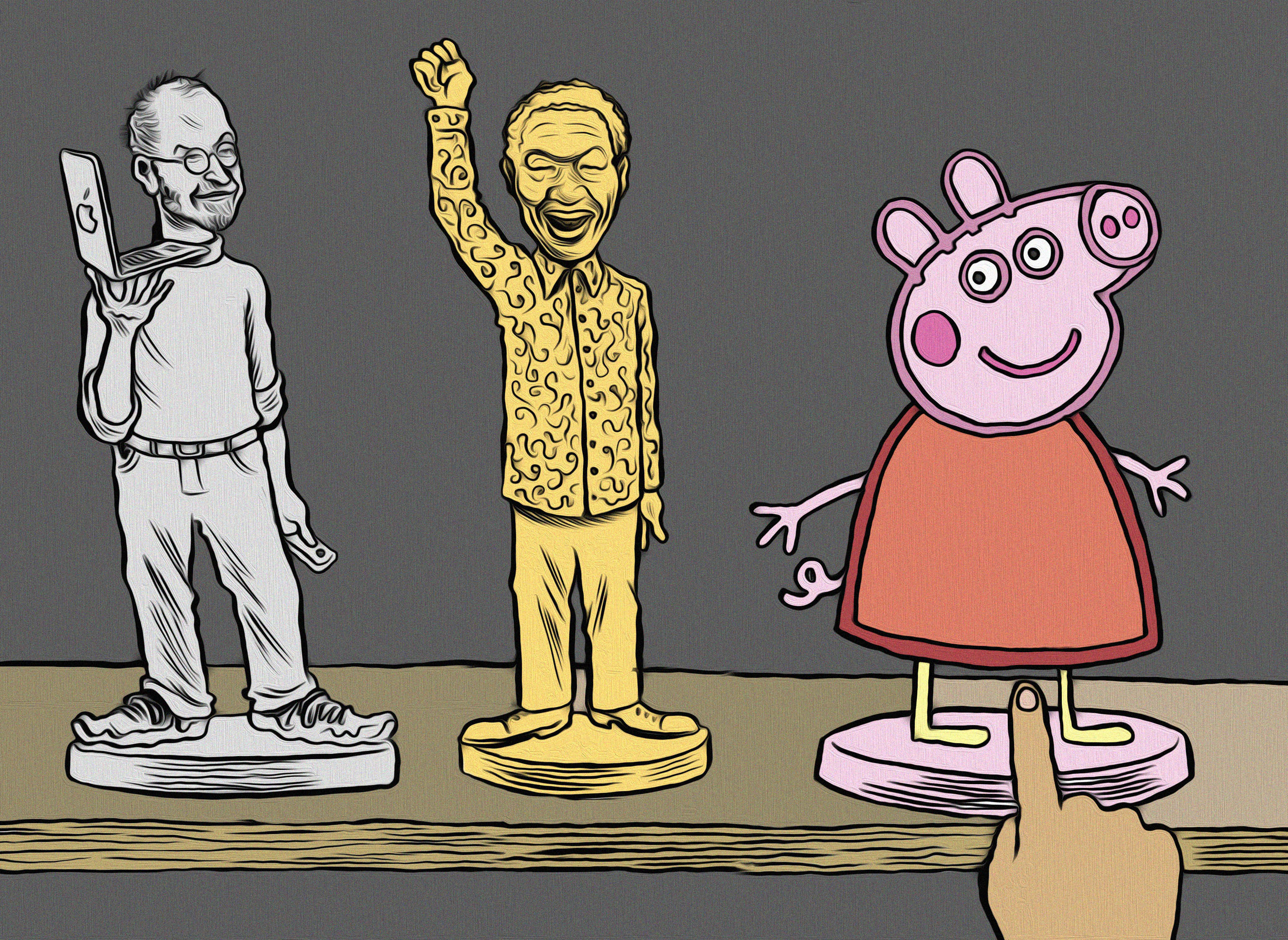

(Graphic: Carlos Amato)

When I was eight, my Waldorf School class went for a camp on a biodynamic farm called Bloublommetjieskloof in the Boland. We were taught how to churn butter and stare at goats, and one rainy night we slept in a forest, in shelters made of grass and sticks that we had built with our bare, bourgeois hands. That was a life-changing experience for me — I’ve hated camping ever since.

The next day, we weeded a field under the supervision of the camp host — the late, great Jeanne Malherbe, who was a formidable pioneer of sustainable farming in South Africa. We were sitting and yanking out weeds when she pointed to a cowpat, and asked us to note its distinctive shape. “That spiral form that you see is the cow echoing the spiral movements of the stars and planets in the sky,” she said. Even though I knew nothing about fluid dynamics, I could tell just by looking at the evidence that Malherbe’s theory was a load of kak.

Even so, I didn’t raise my hand and say to Malherbe: “I don’t believe you.” I just nodded and smiled, partly because I wanted to believe her. Because I loved the idea that cows drew a little flow chart of the cosmos every time they took a dump. It was funny and beguiling, and I never forgot it.

Was Malherbe telling us a big, steaming lie — or was she simply giving us something delightful for our brains to seize on, and use as we chose? The easy answer is both, I suppose.

But the answer gets more difficult if we sharpen the question: If you’re an atheist parent, what do you tell your inquiring children about religion and its absence?

The other day, I was reading my three-year-old son a picture book — Tabby McTat, The Busker’s Cat, by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler. He is a connoisseur of towers, and he spotted a church steeple poking from the background of a London street scene.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“It’s a church,” I said.

“What’s a church?

I paused for a second.

“It’s a place where people go to sing songs.”

As parental cop-outs go, it wasn’t a biggie. It was bedtime, and I reckoned both of us were too tired for a discussion about gods. He’s also about three years too young for that discussion, and I felt about three years too old for it.

But the exchange did alert me to the task that awaits my wife and me in the years ahead. I suppose that task will be easier than the related one facing religious parents, who must surely feel obliged to give their children a robust argument for their own brand of faith, one that stands up to the formidable weight of the case against. In the long run, the odds of success in that project are not good.

But the atheist or agnostic parent has another, possibly bigger problem: How do you offer your children a godless belief system that is as emotionally energising and consolatory as religion (in its gentler variations) can be? To put it more graphically, if you can’t put stars in their cow shit, then what else can you put in it?

(If you’re a parent already, it’s way too late to become a devotee of the world-renowned University of Cape Town philosopher David Benatar, who argues that having children at all serves to increase the sum of human suffering and should be avoided purely on ethical grounds.He states baldly that our pleasures in life are outweighed by all the pain we have to wade through,from grief to trauma to the myriad small affronts of being cold or hot or hungry or sore or bored. His “antinatalist” verdict on the human experience is impressively chilly, but perhaps the act of reading Benatar is itself the tipping point that makes your life a pointless ball-ache. In any event, his message is not suitable for children.)

The long ideological sales pitch we make to our children is made for our own sake as much as theirs. It’s a defence of our status as domestic authorities. Children are a tough crowd — they have the critical distance of Martian emissaries, and they’re not afraid to use it. So we need to get our story straight if we want to have some clout in their lives. If we want them to behave, in other words, without resorting to authoritarian or violent parenting.

And just like religious believers, we self-satisfied atheists have learnt to ignore the cracks between our professed convictions and our actions. A large proportion of atheists are middle class. Most of us believe that gross economic inequality is morally indefensible,but we don’t transfer property or advantages to people who are poorer or less advantaged than us. We don’t actively support humanitarian causes as readily as religious people do. We may believe that capitalism is an evil economic system,but we don’t abandon it to barter eggs for toast in anarchist communes. We may believe that anthropogenic climate change is real, but we don’t eliminate our carbon footprints. (Congratulations to any unbelievers who have done all these things,but I’m not talking to you.)

Our children are liable to be harsh judges of our ethical and ideological integrity,but they also exert an equal and opposite pressure on parents.

They make us want to be selfish to protect them from precarity and suffering — not least in a disfigured society such as South Africa, in which individual fulfilment and liberty can seem so brutally predicated on the elite commodities of private education and healthcare.

Where do you draw the line between a protective instinct and atavistic greed? The apparently noble impulse to help one’s own children can trigger some ignoble secondary impulses — insatiable accumulation, crime, a callous coldness toward all the suffering of human beings who aren’t our children.

And it doesn’t help matters that the world is growing more unfathomable by the day if you don’t carry the divine-intervention card in your back pocket. We atheists tell ourselves that the secular fairy tales are crumbling. For example,the case for democracy as the definitive political environment for progress and justice has been a touchstone for secular humanists in the last 50 years. But that argument now resembles King Lear, ranting impotently in the wilderness as its populist children run amok. The same goes for the cobwebbed notion that incrementalist free-market economics leads inevitably to universal prosperity and happiness.

The liberal idea, in short, is now an undead creature. Not because it hasn’t made the world a better place — it has patently done so, as shown with hard data by the new optimists such as Hans Rosling and Steven J Pinker — but because it can’t make the world a just place, or a just-enough place. And that, increasingly, is what we want.

No surprise, then, that socialism is making a roaring comeback across the young West. But as an indebted forty something harbouring unapologetic dreams of financial security, I can’t honestly raise my children on a diet of revolution. Because, to date, socialism’s only successful, democratic iterations — the Nordic states — are not really socialist at all. They are small and conformist societies nourished on oil and furniture multinationals, whose domestic histories are unscarred by oppression; cradle-to-grave welfare in a country in which everyone is a millionaire does not amount to a viable template for global socialism. Nor does the Venezuelan nightmare or Cuba’s authoritarian dream.

The socialism I want to believe in must deliver liberty and equality and democracy all at once. I don’t back the likes of Jeremy Corbyn or Julius Malema to achieve that. Until someone figures out how to do revolutions properly, I won’t be reading my children Marx for Beginners while they toast their marshmallows.

What about science, then? It has long been a sturdy buttress of the secular dream, and it is still helping us live longer and equipping us to save our environment. But its gifts are still lavished disproportionately on the already privileged. Artificial intelligence, that mutant spawn of the scientific mind, is surveilling our children to smithereens if it isn’t obliterating half the jobs they dream of doing. “No, you can’t be a fireman, Johnny, because you’re a flawed and mortal beast.”

On the other hand, the fight to prevent a global environmental catastrophe is more than urgent enough to captivate young minds, as evidenced by the wave of youth protests against policy that does not deal with climate change. Like a religion, the green cause can turn fear into hope.

But that struggle is surely too complex, too enmeshed in the granular mess of the real, to meet the mythical demands of a child’s imagination.

Or, for that matter, an adult’s imagination. No rational, secular worldview can compete with the totalising potency of myth and religion. This is why political philosophies cannibalise the structures of myth and religion — such as the motif of ancestral presence and sacrifice — to gain power and entrench it.

Post-apartheid South Africa needed the story of Nelson Mandela’s sacrifice and forbearance to legitimate its incomplete revolution. But 20 years later, the organising power of that story began to crumble. Not because Mandela wasn’t a moral giant,but because no myth of ancestral sacrifice or forbearance is strong enough to make sense of contemporary injustice.

What will I tell my sons about Mandela when they’re a bit older? That he was a great redeemer of South African sin, but we failed him? Is that any more truthful than the story of Christ?

And if I do tell them that version, will they shrug and yawn and ask me for money for Fortnite skins? Or will they ask me why Mandela opted for forgiveness instead of justice? And if they do, what will I say? I don’t know yet.

But that’s a long way off. For the foreseeable future, our family will muddle our way through. We might even choose to believe that cows can shit galaxies. We will believe in Father Christmas, in Tabby McTat, in Peppa Pig, in Harry Potter. The small gods of childhood are god enough.

And when those small gods fade, our childrenwill tell us what to think.