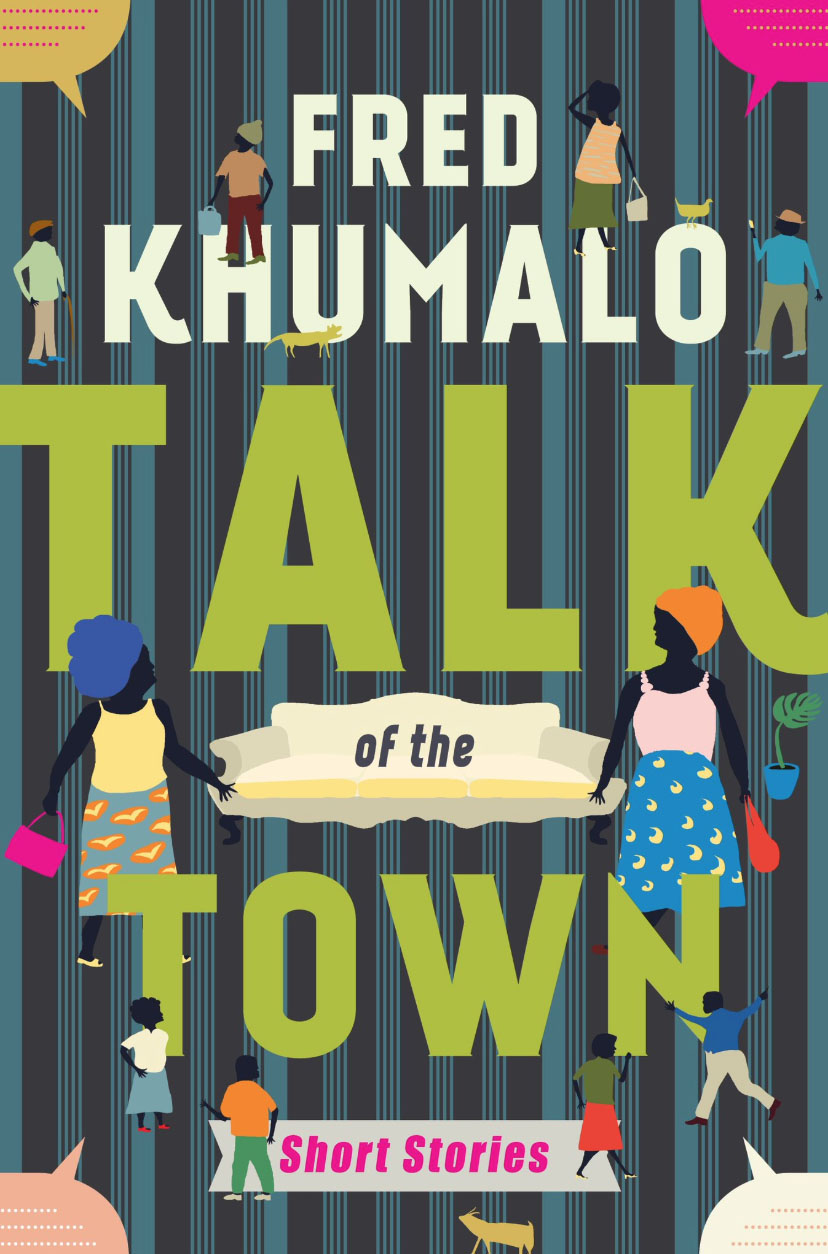

Masterful: Fred Khumalos new collection of short stories in 'Talk of the Town' explore African identity politics, xenophobia and criminality, among other things. (Madelene Cronjé/M&G)

TALK OF THE TOWN

by Fred Khumalo (Kwela Books)

Novelist, newspaper columnist and short story writer Fred Khumalo enjoys considerable but still insufficient presence and acclaim in the realm of South African letters.

From Bitches Brew, Touch My Blood, Seven Steps to Heaven and Dancing the Death Drill to numerous columns in the national press, Khumalo the journalist and Khumalo the author interface in creatively charming and artistically resonant ways. There is, in his journalist, novelist and short-story writing continuum, understated but potent reportage and inventive instincts in his choices and manner of execution. There is also attention to detail in the thematic range and sensory euphoria emanating from the beauty and intensity of how he envisions and plants words on a page. It is not a given that the complementary nature of journalistic and novelistic pathways lead to fertile and rewarding artistic destinations in the universe of fiction writing. Gifts or powers without restraint or class can become mediocre and pedestrian indeed.

Talk of the Town, his collection of 10 short stories, confirms Khumalo’s mastery and brilliance (words often mindlessly used in cut-and-paste fashion in some art reviews and critique) with interplay between language and narrative, nationhood and geopolitics and tensions between history and cultural specificities and generalities.

The stories have a fully formed and resilient backbone, are self-aware without being navel-gazing diatribe and exude an almost floral sense of multidimensional consciousness. The prose is blowtorch assured, the pace bullet-fast without being sloppy and the emotional range shifts from cruel to charming, meditative to shocking, laugh-out-loud hilarity to knotted-throat anger and pain. At full throttle, the individual and collective texture of the writing displays great skill and craftsmanship, as well as the emotional and intellectual maturity to tackle a diverse range of themes: such that the cumulative force of the examination of the human species at home and abroad propel the reader from one feeling to the next with a power akin to jet engine thrust: commanding, assured, gravity defying.

The difficulty, and perhaps exhilaration, of writing and reviewing short stories is the fact that they are, in some oblique but not total way, compressed worlds of novels in that the narratives need to take off from very short and sometimes precarious runways. The brilliance and mastery alluded to earlier is much earned, for there is ample and compelling evidence that the collection is highly distilled from the perspective of complex theme-framing and presentation. A bird’s-eye view of the narrative and thematic pillars of the stories recalls a symphony (the writing is that melodious) of images and counter-reflections from xenophobia, Afro-pessimism, African Renaissance sentiments in Beds are Burning. There are cultural systems colliding with blatant criminality in The Invisibles, conundrums and comedies of lust, eroticism and gender sensitivity classes in Learning to Love and the slippery nature of criminal mindedness in TP Phiri, Esquire.

But what exactly constitutes the literary distillation, brilliance and mastery, the ample and compelling evidence that define the Talk of the Town collection? First is elegant and contextually rooted humour, then the dialogue as transmitter of ideas and the conveyor belt of narrative (including pitch perfect Nigerian and Malawian accents) and third, the calibration of big themes (gender relations, male sexuality and misogyny, the aspirational and actual in the relationship between South Africa and the wider African continent, and views and identity politics between Africa and Africans in the diaspora, particularly the United States in This Bus Is Not Full ), to fit into and achieve interpretative luminance within the limiting and confined parameters of the short story. Further exhibits concern understated cerebral tapestry and charge embedded in the stories, for we often forget that writers are and must first be thinkers, preferably of the intelligent and curious sort.

There is, of course, the overarching question and demand of artistry — which, though subjective, either shines or self-destructs depending on the extent of the writer’s predisposition to literary aesthetics, articulation of dominant and important themes, and the ability to convincingly evoke places and persons without resorting to flamboyant yet hollow writing.

So: there is weight and solidity to Khumalo’s writing, a love and reverence for language and a naughty streak that is at once delightful, and of a certain permissible corruption, a knowing and polished examination of human beings across their primal and sensory hungers and passions. You can see and smell Hillbrow and Berea with their penis enlargement and ghetto Viagra industries in the stories, marvel at wanna-fit-in-America “Mandela niggas” cursing like sailors, the almost impossible personal, moral and existential choices emanating from Zimbabwe’s historic political ghosts and misrule in Queenface.

To find fault with these stories, one would have to be a cantankerous reviewer — except it should, tongue-in-cheek, be criminal if not treasonous that Kwela Books did not, for a writer of Khumalo’s stature and experience, use a more befitting and dignified image for the outside back cover of the book. But, it must also be noted that authors have veto powers over these things, so perhaps it is misguided and presumptuous to conclude that the image does not tickle Khumalo in the right places.

Talk of The Town is a fine collection of complex and highly contagious writing, the treasonous author image notwithstanding.