Figure exploitation: The National Party makes use of FW de Klerk in its electoral campaign in Soweto in 1994 (Georges Merillon/Getty Images)

General election season in South Africa means trees, utility poles, walls and fences are all dressed up in messages that tell us to “Vote … May 8 2019” in bold letters and political party colours. So, as vote counting reaches its conclusion and the 2019 general elections montage nears its fade-to- black moment, the Mail & Guardian takes a look at how the country’s use of visual messaging has evolved over the years.

Campaign posters exist to persuade the undecided. CNN’s Carol Wells reported on studies that show that “the more signs out there, the more popular that candidate will appear”. But before their use in South African democratic election campaigns, posters were an artistic means of spreading hard news.

As the late activist, playwright, painter and musician Matsemela Manaka puts it in Judy Seidman’s book Red on Black: The story of the South African Poster Movement, the art of the 1980s “reflected the struggling and resisting masses. Its allegory reflects workers in protest against the management, people resisting forced removals, people protesting against any form of injustice, and above all, art has become a tool for liberation.”

One of the collectives responsible for this use of posters was The Medu Art Ensemble. Formed by exiled South Africans in Gaborone, Botswana, this arts collective argued for art that would speak to South Africans in townships, who were unlikely to engage with works in a gallery setting. Their medium of choice became posters with anti-apartheid messaging. The posters were smuggled into South Africa in the evening for them to adorn walls in public and office spaces by that morning.

Even though the posters would be removed shortly after their installation, their use of imagery, symbols and slogans that spoke to the communities in townships created an approachable means with which to engage with art, while adding to the political discourse of the day.

“These would become our messages,” said Seidman, an American cultural worker and visual artist who relocated to South Africa. Before becoming a member of the ensemble in 1980, Seidman worked as a painter in Lusaka, Zambia, from 1972 to 1975. While there she made occasional graphics for the South African liberation movement.

“While I did the drawing and design, most often the conception, graphics and words reflect[ed] discussion, ideas and inspiration generated within the collective,” explained Seidman in reference to one of her posters, in which a woman holds up a broken chain in a defiant fist. The poster’s text reads: “Now you have touched the woman, you have struck a rock; you have dislodged a boulder; you will be crushed.”

Medu operated from 1979 to 1985; the collective’s poster-producing division came to an end when the South African National Defence Force raided and destroyed it, killing many members. The poster division had by then made more than 50 poster stencils, from which an unrecorded number of posters were printed, smuggled into South Africa and exhibited in the public domain.

sThe ensemble’s demise coincided with South Africa’s State of Emergency — a time characterised by an exponential rise in shootings, detentions, bannings and bombings — but the production of resistance art continued to further the struggle.

Medu’s posters were employed as a tool for liberation, but the use of visual messaging as a rallying tool and for taking a stance was also used by the far right. For example, National Party posters focused their message on anti-ANC messaging during this time. One such poster, written in Afrikaans, translates to: “A voice for the NP is a voice against the ANC. Choose National Party.” Unlike the anti-apartheid posters, which made use of imagery to get the message across, the National Party’s catchy rhyme is accompanied by a small picture of the party’s president, FW de Klerk, along with its logo.

Far-right posters would also shut down democratic opposition by labelling their contenders as arrogant and corrupt communists. Other posters went as far as depicting black people as blind rats for supporting the ANC.

When Nelson Mandela was released from prison and often appeared in public with De Klerk, the National Party’s Herstigte Nasionale Party spread the “Stop De Klerk and Mandela. Vote No” campaign.

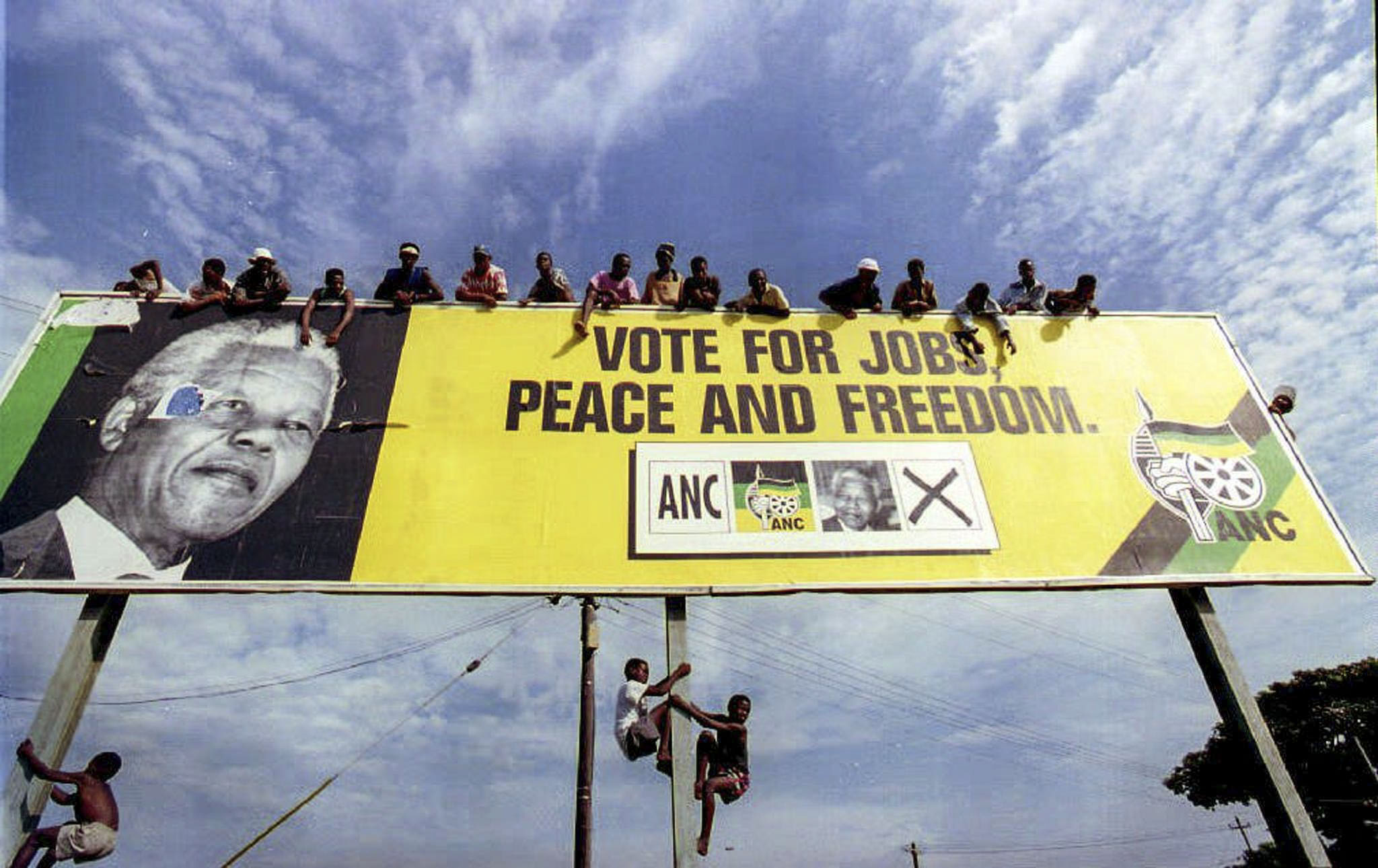

Soon thereafter, the monopoly of far-right parties was eclipsed by the unbanning of liberation movements and the dawn of democracy. Each of these movements employed their own set of political tactics or gimmicks with which to curry favour. It was during this time, leading up to the 1994 general elections, that the ANC began promising land redistribution while riding the Mandela trope wave.

ANC supporters lean over a billboard in a township outside Durban as they await the arrival of Nelson Mandela at a pre-election rally in KwaZulu-Natal. (Alexander Joe/AFP)

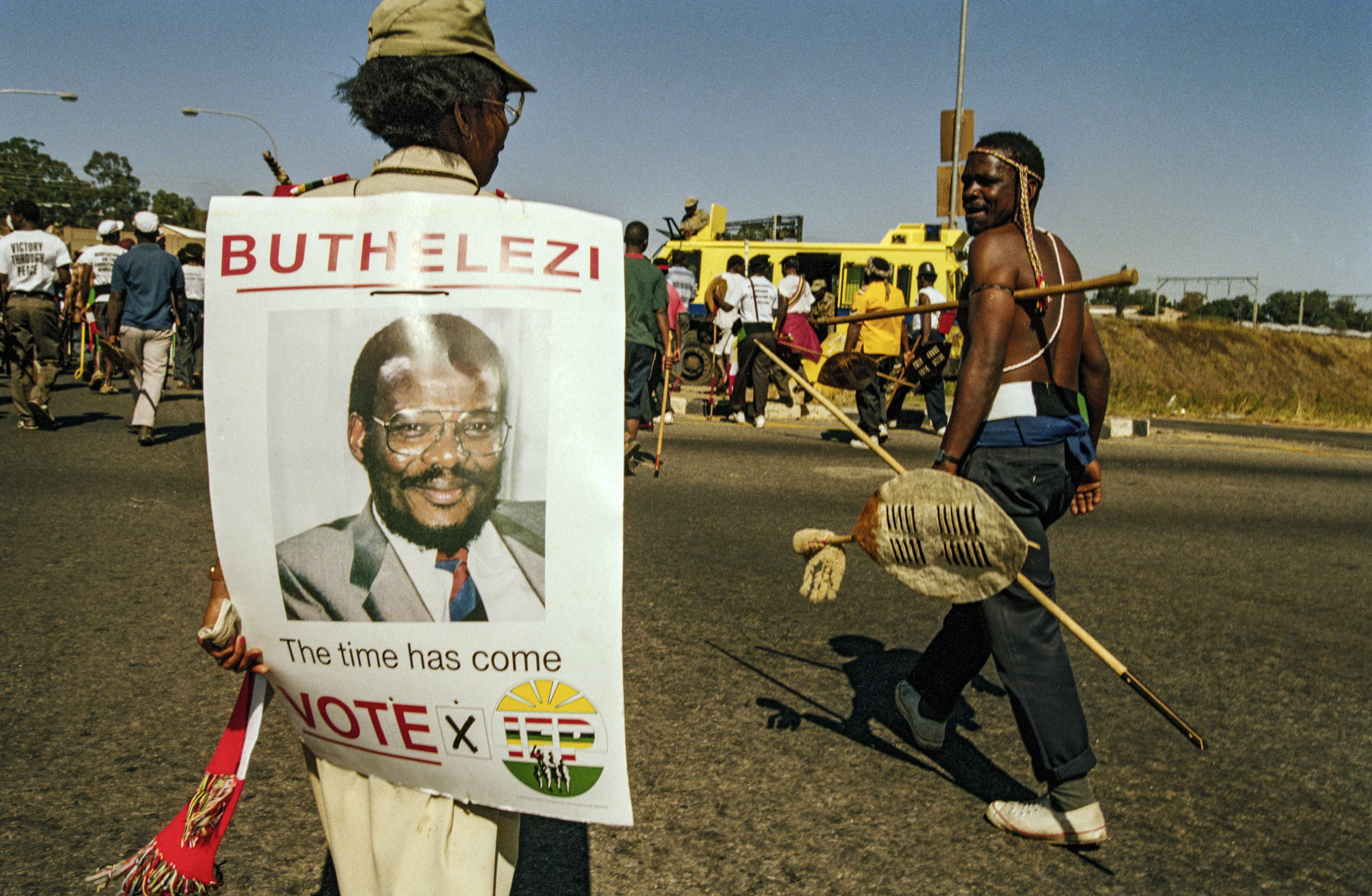

Much later, ahead of the 1999 elections, Bantu Holomisa’s United Democratic Movement (UDM) attempted to capitalise on the idea of reconciliation and a rainbow nation by vouching for partnership, while Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) got its message across using Afrikaans. One such IFP poster, with a portrait of Buthelezi, said: “Die man wat u kan vertrou (the man you can trust).”

The National Party tried its luck by using isiZulu on a poster, saying: “Umthetho-sisekelo wokuthula”, which translates to “a peaceful Constitution”.

Team colours: IFP supporter adorning a poster leading up to the general elections. (David Brauchli/ Sygma/ Getty Images)

By the 2000s, when the ANC had established itself as the undisputed choice for the general elections, opposition parties’ visual messaging began highlighting the ruling party’s faults. A 1999 National Party poster read: “ANC destroyed 1.5-million jobs.” In 2004, a UDM banner read: “10 years of unemployment undermine the people’s freedom.”

This trend has continued, 25 years into democracy. With the emergence of ANC descendants such as Cope (Congress of the People) in 2008 and the EFF (Economic Freedom Fighters) in 2013, the trend has intensified. This year, the Democratic Alliance brought out billboards that read: “The ANC is killing us” and “The ANC has killed the lights, affecting 57-million South Africans!” — touching on the ruling party’s leadership shortcomings with regards to Marikana and Eskom. In addition to these, posters for the current general elections play on the themes of land, employment, service delivery and an end to corruption.

(Delwyn Verasamy/ M&G)

James Findlay, of the James Findlay Collectable Books & Antique Maps store, told Business Insider’s James de Villiers that focusing on these faults may be a necessary auxiliary to the generic portraits of the parties’ leaders that we see every year. Findlay, who has collected election posters for over 20 years, says this is because the visionary gazes that party leaders such as Cyril Ramaphosa, Julius Malema, Mmusi Maimane, Pieter Groenewald and even Andile Mngxitama give the public do not necessarily have the clout that an image of Nelson Mandela or Che Guevara has, because one is directly associated with South African democracy and the other with the Cuban revolution.

Coupled with the likes of the Independent Electoral Commission’s Xsê campaign, election posters today seem more effective in creating the type of hype that comes with retailers putting Christmas decorations up before December 25. The generic head-and-shoulder portraits and finger-wagging posters filling our streets don’t seem to tell us much about how the parties plan to make the next five years better than the last 25. Perhaps this justifies their current existence — an existence entwined with telling debates, interviews, inquiries and politicians’ Twitter feeds. Perhaps it is enough that election posters simply encourage us to keep voting.