National Assembly speaker Baleka Mbete once famously said that South Africa now has a culture of 'zero tolerance for no women in politics' (David Harrison/M&G)

GENDER

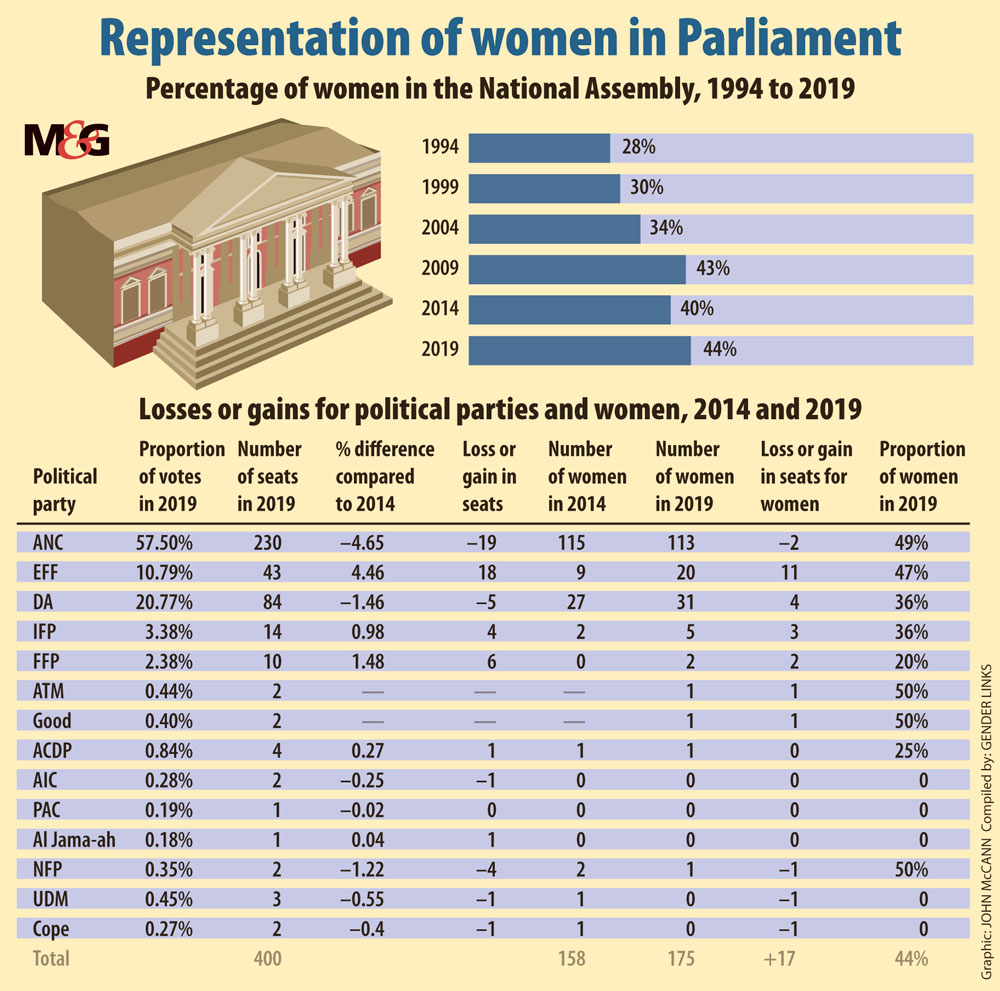

National Assembly speaker Baleka Mbete once famously said that South Africa now has a culture of “zero tolerance for no women in politics”. Despite the drop in support for the ANC, which has been the mainstay of steady increases in women’s political participation since 1994, the May 8 election broke new ground in delivering 44% women MPs (four percentage points higher than in 2014), thanks to smaller parties finally pulling their weight.

But in the absence of a legislative quota, South Africa still fell short of the 50% target and remains at 10th place in the global stakes where countries such as Rwanda, Cuba and Bolivia have reached or surpassed the parity target.

In the 2019 Parliament, the ANC will be down 19 seats, two of these held by women. The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) is up 18 seats; 11 of these held by women. The Democratic Alliance (DA), Inkatha Freedom Party, Freedom Front Plus and smaller parties will together bring 11 additional women, and three smaller parties lose one woman each. This brings the net gain to 17, or a total of 175 women out of the 400-seat National Assembly, a meteoric rise from the pre-democracy Parliament in which women constituted just 2.7% of the total.

But what has really changed?

None of the main political parties achieved gender parity in the top five lists. Casting doubt on the depths of the ANC’s commitment to its voluntary one man, one woman “zebra” quota in its electoral lists, the party found itself in an internal squabble with its Women’s League for appointing only two women out of eight provincial premiers — Sisi Ntombela in the Free State and Refilwe Mtsweni in Mpumalanga. The North West premier was still to be announced at the time of going to print. In a bizarre attempt to make amends, the ANC said provinces with male leaders would have 60% women representation in their executive committees.

The EFF has the most progressive gender provisions, including among others fighting gender-based violence and sexual harassment, educating men on misogyny and patriarchy, and empowering women economically. The party includes comprehensive actions on the rights and protections of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and questioning people. Yet the election witnessed a below-the-belt public spat between EFF leader Julius Malema and journalist Karima Brown.

She inadvertently sent a brief regarding an EFF campaign meeting in Ekurhuleni’s Ward 6 to an EFF WhatsApp group as opposed to her eNCA colleagues. Malema responded by posting Brown’s contact details on Twitter without her consent. EFF supporters attacked Brown on social media, allegedly threatened her with rape and made vitriolic racial attacks against her. “We are not playing here. We are dealing with racists … step aside or we will crush your prolapsed vagina,” was one of the comments she received, accompanied by laughing emojis. Another called her an “Indian whore”. Brown lodged a case against Malema in the high court. The outcome is still pending.

The DA has long opposed quotas for women in politics. Its former leader, Helen Zille, sparked a heated debate and an equality Court challenge in the last elections for appointing an all-male Cabinet.

The message of “zero tolerance for no women in politics” (except the boss) is gradually sinking. Despite five seats less in Parliament after the 2019 elections, the DA will have four more women than before. Beneath this veneer and a much improved reflection of gender concerns in its manifesto, many questions remain on the DA’s gender politics.

The public feud between DA leader Mmusi Maimane and Patricia de Lille that led to her resignation as Cape Town’s mayor and as a member of the DA, and to her subsequently forming the Good party, did little for the DA’s gender credentials. Even in the lead-up to the election the DA’s telemarketing campaign included a message about firing De Lille. The Electoral Commission of South Africa ordered the DA to apologise to De Lille and stop the messaging.

Although De Lille is the comeback kid in the 2019 elections (now one of two women party leaders in the new Parliament), the DA’s failure to embrace up-and-coming black female leaders such as Lindiwe Mazibuko is one of the factors being cited for its lacklustre performance in 2019.

The spotlight in the post-election analysis remains on President Cyril Ramaphosa, whose personal popularity helped to rescue the ANC from an even bigger slump in popularity. For gender activists, Ramaphosa represents a welcome break from the era of Jacob Zuma, whose presidency witnessed much backlash and backsliding on South Africa’s fragile gender justice gains. Among others, Ramaphosa initiated the first-ever presidential summit on gender violence in November last year.

But the president came under criticism for appointing Bathabile Dlamini as minister of women’s affairs after her dismal performance as social development minister with many saying he did so because of her position as head of the ANC Women’s League.

Will his personal election boost give him the courage to rise above party politics and make more principled appointments in the soon-to-be announced Cabinet? This is a crucial litmus test for Ramaphosa’s so far timid ventures into feminist politics.

Colleen Lowe Morna is chief executive of Gender Links and Kubi Rama is an adviser to the organisation