Recent amendments to the Labour Relations Act help ensure that labour registrar Lehlohonolo Molefe can do his job without interference. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

For decades the office of the labour registrar had been largely overlooked. But in recent years the registrar, who is tasked with ensuring that trade unions comply with the law, has been thrust into the centre of the political tug of war between government and organised labour.

Lehlohonolo Molefe, who was appointed labour registrar last year after a lengthy dispute between his predecessor and outgoing labour minister Mildred Oliphant told the Mail & Guardian this week that more than 100 unions have been sent letters by his office since his appointment in May last year.

The letters are warning shots, indicating noncompliance with the Labour Relations Act (LRA) and instructing unions to address this.

The registrar can place organisations — including trade unions, employers’ organisations and bargaining councils — under administration and deregister them if they fail to comply with their constitutions and the parts of the Labour Relations Act that govern them. If a trade union is deregistered, it loses organisational rights and the right to represent its members.

Molefe’s actions in recent months have been the subject of public scrutiny, as he has moved to take steps against a number of high-profile trade unions. These include the South African Municipal Workers’ Union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) and the Food and Allied Workers Union (Fawu).

He has fielded accusations of being politically motivated in targeting unions not affiliated with trade union federation Cosatu. Numsa and Fawu are the two biggest unions in the South African Federation of Trade Unions (Saftu). With about 700 000 members, Saftu has emerged as a powerful opposition to Cosatu’s dominance.

The vulnerability of the labour registrar’s office to political interference was put in sharp relief in 2015 when Molefe’s predecessor, Johan Crouse, was suspended and accused of “gross insubordination” when he attempted to place the Chemical, Energy, Paper, Printing, Wood and Allied Workers Union (Ceppwawu) under administration.

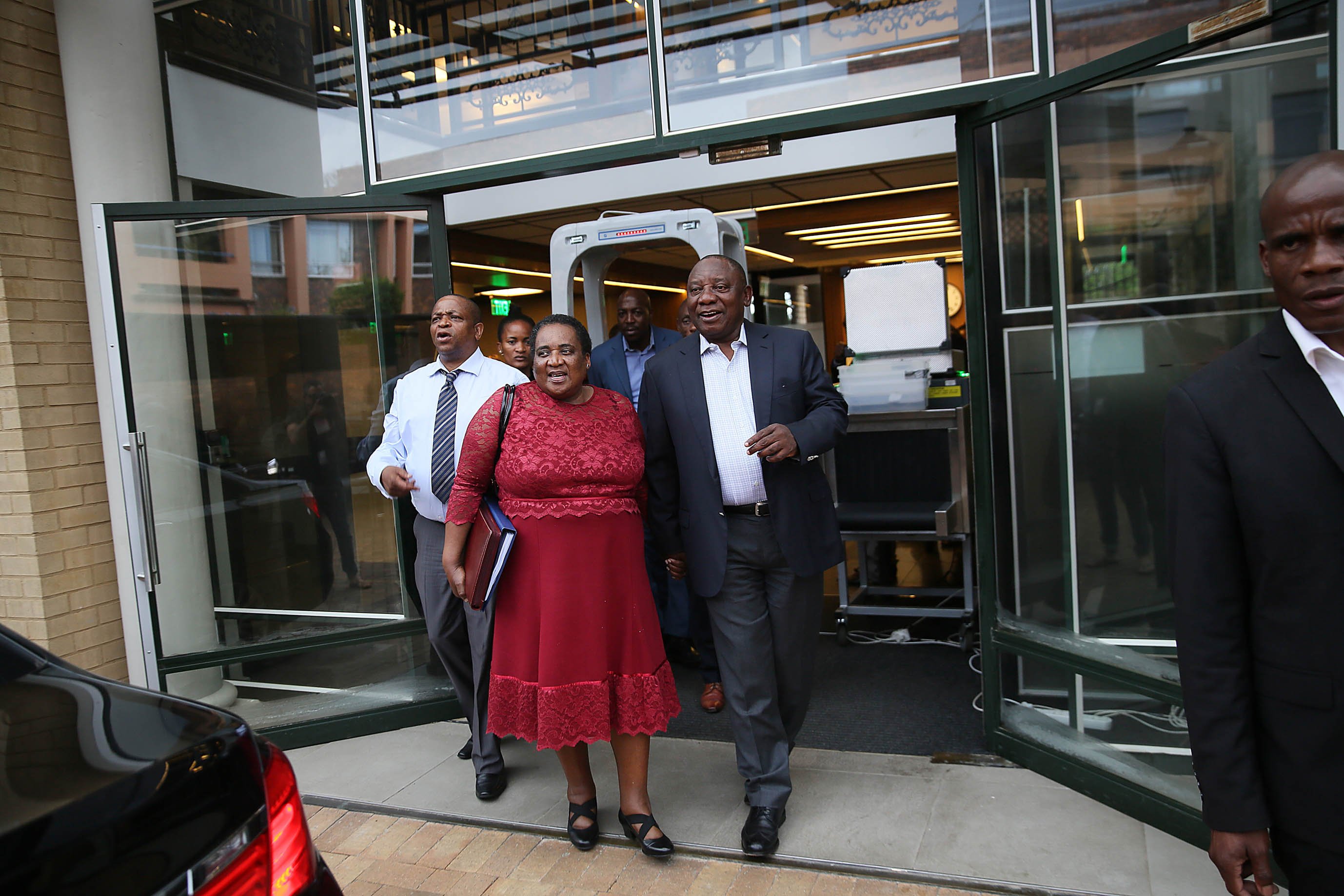

Molefe’s predecessor was suspended by then labour minister Mildred Oliphant (above) when he tried to act against the Chemical, Energy, Paper, Printing, Wood and Allied Workers Union. (Alon Skuy/The Times/Gallo Images)

Minister Oliphant was accused of protecting Ceppwawu, a Cosatu affiliate. In 2017 the Labour Appeal Court ruled that her suspension of Crouse was “irrational and invalid”.

The court made no determination on whether Oliphant unlawfully interfered with the functions of the registrar, but ruled that there was no legal basis for expecting the registrar to “report or account to the minister”.

Crouse, who had worked in the labour department for almost four decades, was reinstated but he only had a few months more in the department before he reached retirement age.

Molefe took steps to put Ceppwawu under administration when he took over from Crouse.

Ceppwawu. (Paul Botes/M&G)

This week, Crouse said that the office of the labour registrar was more or less ignored until he took action against the union. “The minister had been there for years and yet she had never even met me while I was there.”

But the office of the labour registrar was suddenly drawn closer to the minister’s line of sight when the Ceppwawu saga kicked off, Crouse told the M&G. He said the independence of the registrar, which he described as “at the bottom of the department of labour”, was put in further jeopardy when it was forced to report to the director general “who is directly under the minister”.

Recent amendments to the LRA, which were ushered in alongside the National Minimum Wage Bill, provide for the independence of the registrar’s office. The amendments came into effect in January.

“The registrar and the deputy registrars are independent and, subject only to the Constitution and the law, they must be impartial and must exercise their powers and perform their functions without fear, favour or prejudice … No person or organ of state may interfere with the functioning of the registrar,’’ the amendments read.

But Crouse suggested that the minister would probably still wield a degree of power when it comes to the decisions of the registrar to take action against certain unions.

Molefe argued that this would not be possible, saying that the amendments to the LRA “are just strengthening” the independence that he has already enjoyed. “Since I have been in this office, I have not seen any interference. From the minister or the director general. I have been working.”

Molefe said that he simply informs the director general and the minister of his decisions.

“And that’s it basically. I do not see it as interference. I tell them the decision I have taken. Whether they agree with it or not, is something else … I have not come to a point where they have said: ‘We have a different view.’ Even if they had that view, it would not change my mind because the law is quite clear,” Molefe said.

“I guess the buck stops with me.”

Molefe, who has spent most of his career working in legal services at the department of labour, said he took his cue from the court judgments on the fate of the previous registrar.

He said that he is guided by the law in the actions he takes against unions. “There are laws in place. And it is a question of checking whether particular unions are in compliance with what the law says and making them aware … If you are going to play hide and seek, my job is to apply the law. That’s it. I have said that I will not tiptoe around noncompliance.”

Molefe has taken this sentiment seriously: more than half of the registered trade unions have been sent

letters by the registrar’s office warning them of their alleged noncompliance.

“My position was taken from what everybody knows is out there already. There have been so many reports of corruption and dissatisfaction of members,” he said.

“So we need to restore order. The only way to restore order is to apply the law.”

Molefe said the fact that he has had to send about 110 letters to trade unions warning them of their alleged noncompliance is a bad sign for the state of South Africa’s unions.

“Things do not look good,” he said, adding that trade unions have been given an opportunity to respond to allegations of noncompliance before action is taken against them.

Molefe has taken note of the criticism he has received, but reiterated that his decisions are not swayed by any political affiliation. “My mind is clear. I sleep peacefully at night. I know that there are people who will go around saying that it is politically motivated and what not.

“Let me tell you this: I do not belong to any political party. I have never belonged to any political party … I don’t have time to be listening to what politicians have to say. I am an officer of the court and I am a public servant. That is the bottom line for me.”

But there are concerns about a possible agenda behind the crackdown on unions. Numsa spokesperson Phakamile Hlubi-Majola said the recent action by the labour registrar smacked of efforts to “deal with unions that are at the forefront of fighting for workers’ rights in South Africa”.

“These are efforts to try and silence militant unions and to stop them from doing that work. I mean this is a question we must ask,” she said.