Energy drain: The giant pipe through Riversands transports 460 megalitres of sewage a day. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Sewage can be a mess. It despoiled the Vaal River so badly that the army had to be called in, and recently a plant failure turned Durban harbour into a giant latrine.

Eskom struggles to manage its runaway debt and to keep the lights on, threatening not only the country’s power supply but our public finances too, while the heavy reliance on coal for electricity and fuel makes South Africa a notable contributor to the climate catastrophe.

Can these problems be turned into opportunities, environmental disasters into desired outcomes, and costs into a revenue stream?

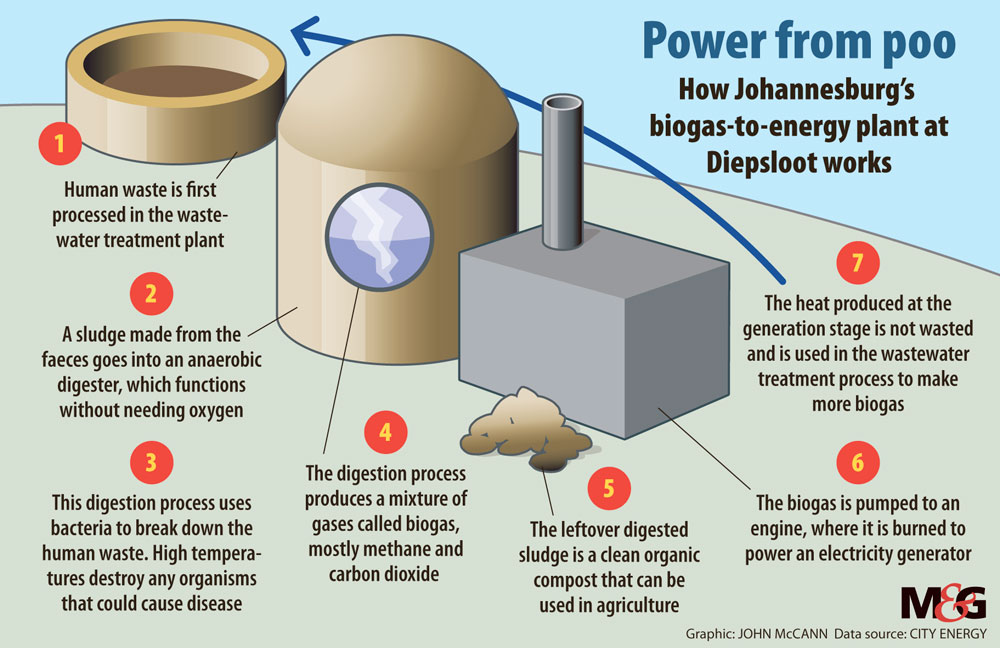

Sewage needn’t be a mess. It can be used to make electricity. I could not think of cases in South Africa, but on inquiry was surprised to find we have such a plant at Diepsloot on the Jukskei River in northern Johannesburg. This is the largest sewage works not only in the city, but in the country and, according to the pundits, sub-Saharan Africa.

A lot of sewage moves through these works — 460 megalitres a day, fed by a giant 3m-wide pipe, a visible feature of the landscape. This is a vast amount of sewage: Google says it’s the equivalent of 184 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Three large engines, each housed in a structure aboutthe size of a shipping container, stand ready to convert biogas produced in the waste management process, into electricity.

This should make Johannesburg mayor Herman Mashaba happy. In his State of the City address in late April he said the city would approach the courts to be able to secure power from suppliers other than Eskom.

But, the Northern Works facility at Diepsloot operates at only 20% of its capacity because Johannesburg Water has connected just six digesters to the plant. The three engines are idle for most of the time.

Built by WEC Projects with City of Johannesburg funding six years ago, the facility was projected to save the city R100-million a year in electricity purchases from Eskom. Northern Works was intended to produce 4.2 megawatts with six engines installed but could produce as much as 6MW if fully optimised.Projections suggested it would cut Johannesburg Water’s electricity bill by 80%.

WEC Projects says this cogeneration system could recover more than 80% of the energy available — about 38% electrical and 45% thermal energy.

Mashaba’s office had not responded to questions from the Mail & Guardian on the unused capacity at the Northern Works facility at the time of going to press.

Captured biogas from digesters comprises predominantly carbon dioxide and methane, a potent greenhouse gas used, in this case, to power the engines. Biogas is a mixture of gases produced by fermenting fresh waste material in anaerobic conditions, making it a renewable resource.Heat energy is fed back into the digesters, adding to the overall cost savings.

The Northern Works plant operates at low levels of capacity because only a limited amount of the treated sewage is made available as biogas. The city appears to be happy to run the facility at levels substantially below its design capability.

Its interest in the plant is apparently so low that cable theft meant the facility did not operate for a year even though it was a relatively simple matter to replace the stolen cable.

The giant pipe towering above Diepsloot transports 460 megalitres of sewage a day. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

The giant pipe towering above Diepsloot transports 460 megalitres of sewage a day. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

The best example of a South African-funded biogas facility that uses South African-developed technology at a municipal sewage works, is in Namibia. The Windhoek sewage works is celebrated as a model of how to optimise wastewater management to achieve desirable outcomes in energy usage and water reclamation. Recycled wastewater is processed to drinking standard,a much-needed initiative since most of the country is a desert.

Andrew Taylor of Cape Advanced Engineering, which has a public-private partnership (PPP) with the city of Windhoek, says it “is the only city in the world that reclaims its wastewater through direct closed-circuit systems — PPPs plus [its] own plants yielding 25% of the city’s potable water and semi-purified water for parks and sports fields —and the best water …is the reclaimed water”.

Taylor says water has been reclaimed and reused since 1968, just a year after human hearts were first “recycled”.He says that more than 9000 biogas plants in Germany produce 5000MW of power (the equivalent of a Medupi coal-fired plant). This is renewable energy “on call, on demand”, he says. Unlike renewables dependent on the sun and wind, biogas can produce energy to meet demand when required.

“Biogas is the only renewable energy source easy to store,” says Taylor, explaining storage can be as simple as using a “papsak” the size of a rugby field, which inflates and deflates depending on its contents.

Biogas plants can be equipped to supply solar energy during the day and electricity after dark, especially during periods of peak demand.

Taylor says the Windhoek example “is the only model on which South Africa’s wastewater plants can be restored —lean and modest cost structure, reusing existing assets and infrastructure, deliberately labour intensive, and contracted as a performance-based PPP with municipal costs reduced by electricity generated — no performance, no pay”.

The Industrial Development Corporation, which funded the project, calculated the electricity saving over 10years would cover operating costs, capital and interest, says Taylor. In addition, there are the climate and water treatment benefits.

This excludes the value of the clean, reclaimed water that leaves the treatment works.

Windhoek is home to 350000 people; its biogas plant can produce between 350 kilowatts and 500kW. Taylor says the electricity generated at a sewage works may not be great in the wider scheme of things, say 500kW to 600kW. This would bethe equivalent, for instance, of a biogas facility on a large dairy farm or piggery.

Water management in South Africa is a mess. Talbot & Talbot, which specialises in water and waste water solutions, quotes the National Water and Sanitation Plan of 2018, which showed 44% of South Africa’s water treatment facilities pose a health risk and 11% are dysfunctional and pose a critical health risk.

But Talbot & Talbot’s Helen Hulett says the huge escalation in water management costs will make municipalities take notice. Electricity prices are up by 230% since 2009 and water by 182%, compared withthe consumer price index, which is up by 70% in the same period.

Hulett says water and energy costs “are increasing at such a rate they are self-driving out of sheer necessity the need to adopt technologies to manage these resources”.