Suave: Ghanaian photographer James Barnor in his youth. The 90-year-olds latest solo exhibition is currently on show in Paris. (James Barnor/ Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

Born on June 6 1929, Ghanaian photographer James Barnor celebrated his 90th birthday this month. His story as an African photographer in the world of transnational photography is a fascinating one. From shooting, developing and printing photos in a makeshift darkroom in his teenage years to establishing his Ever Young photo studio and working as a photojournalist for The Daily Graphic in Accra in the 1950s, Barnor’s story and images capture the early development of studio photography and photojournalism in Ghana and on the continent.

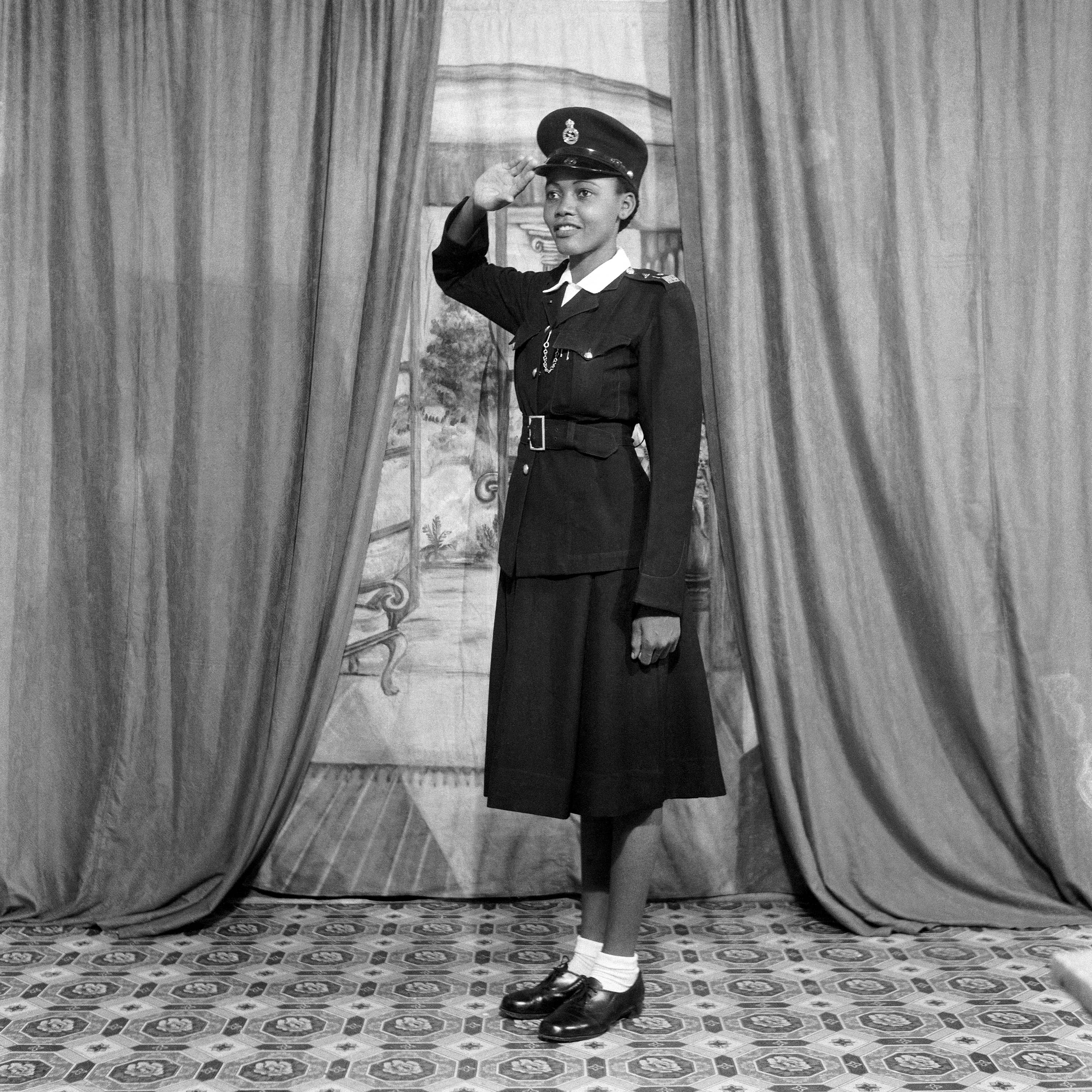

Policewoman Selina Opang has her portrait taken at James Barnor’s Ever Young studio in Accra in about 1954. (James Barnor/Autograph ABP)

Barnor did numerous assignments for Drum magazine, both in Ghana and in England, and developed a close relationship with Jim Bailey, the magazine’s founder and owner. In Accra he captured important historical events such as Kwame Nkrumah’s rise to power in Ghana, the country’s independence in 1957, politics, sport and other special features such as the “Nigerian Superman”, an acrobat on a bicycle.

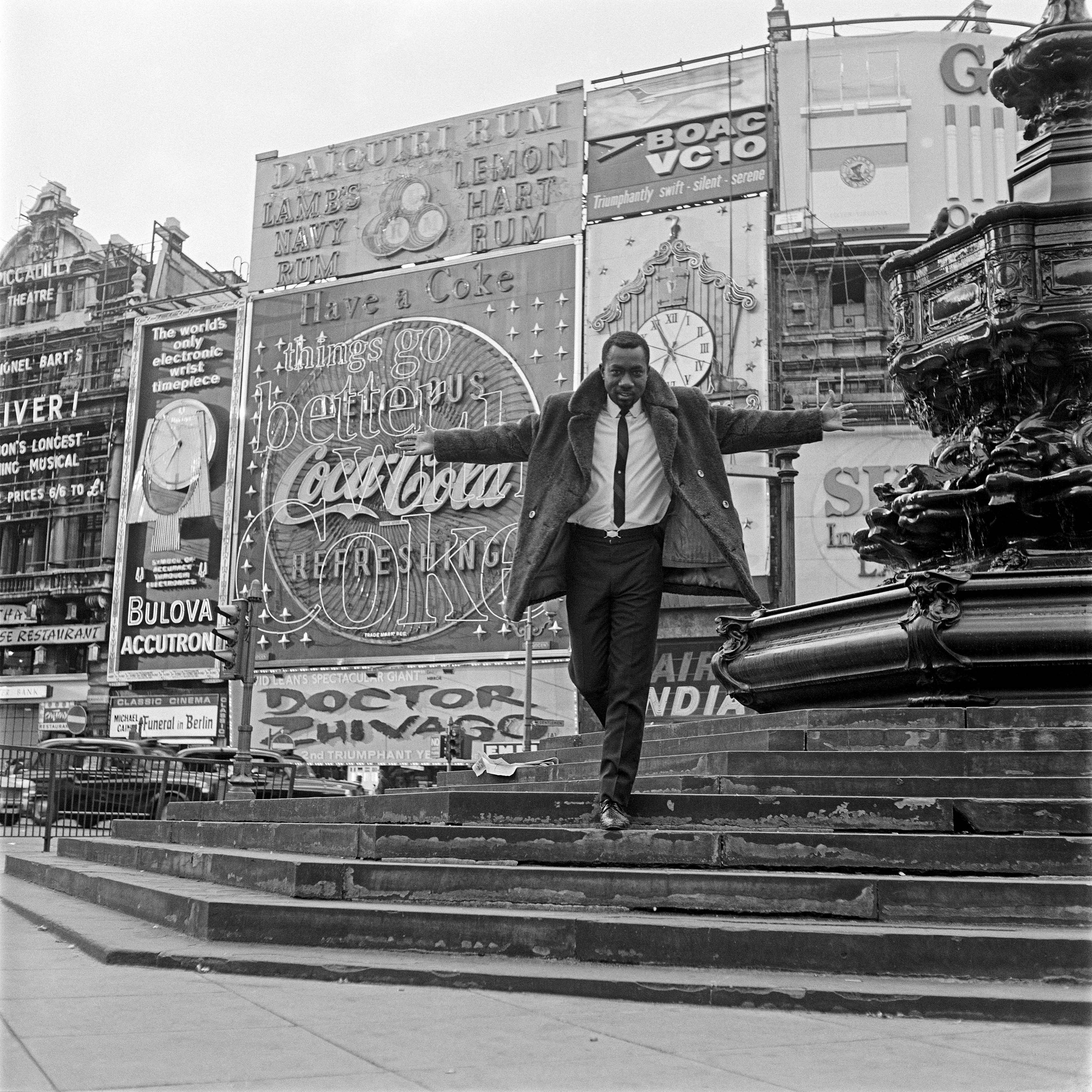

In London Drum assigned him to take photos of Muhammad Ali’s fight against Brian London at Earl’s Court in 1966, BBC Africa radio presenter Mike Eghan in 1967 and portraits of aspiring black models used on numerous Drum covers.

Pulling no punches: Muhammad Ali trains for his fight against Brian London in Earl’s Court in 1966. (James Barnor/Autograph ABP)

Mike Eghan, the first black DJ in London, at Piccadilly Circus in 1967. (James Barnor/ Autograph ABP)

During his 10 years in England, from 1959 to 1969, Barnor studied photography, worked as a technician in photo labs and learnt the art of colour photography, which he put to use on his return to Accra. His 24 years in Ghana from the 1970s saw him establish a second photography studio, X23, and work at the United States embassy, as well as for the Ghanaian president, Jerry John Rawlings.

Barnor returned to England in 1994 and struggled to find work until his images were shown for the first time in 2004 at the Acton Arts Festival and the Ghana@50 exhibition in 2007.

Since his retrospective exhibition at Autograph ABP in London in 2010, Barnor’s photos have attracted international attention from curators, collectors, researchers, galleries and museums. Autograph ABP recently published a book titled James Barnor: Ever Young in partnership with Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

I spoke to Barnor in Paris on the occasion of his latest solo exhibition, Colors, at Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, which runs until June 20. His photos are also included in the exhibition Paris-Londres (1962-1989) — Music Migrations at Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Palais de la Porte Dorée, on until January 5 2020.

There is a photo in your book Ever Young: James Barnor of NT Clerk, who is mentioned as one of the pioneers of photography in Ghana. Last month I came across Felicia Abban’s studio photos from the 1960s and 1970s at the Ghana pavilion in Venice. Do you recall some of the other pioneers of photography in Ghana?

Abban had her own studio. She learnt from her father in the 1950s. There was already another [female] photographer before Abban, whose father taught her and her brother photography. When I was going to school in the 1940s, I used to pass the studio and she was already working there. She was making photos before me but she didn’t get the same exposure; she didn’t go on her own. She continued working for her father, Clerk. Her brother carried on the business after the old man retired. She married a Mr Bulley of Jamestown Stores. I took photos of him too.

On the town: Pioneering Ghanaian photographer NT Clerk (in striped jacket) and friend at Asafoatse Nettey Road, Accra, in about 1974. (James Barnor/Autograph ABP)

Vanderpuiye Studio was another one in Jamestown. He was one of the pioneers of photography in Ghana. In fact, there were two Vanderpuiyes who were photographers. The Deo Gratias studio taught Clerk; the other taught my uncle, my mother’s brother. So photography was all around me. [George] Lutterodt was another one of the pioneers.

Julius Aikins was my mentor and another one of that generation. He led me through the journalistic aspect of photography. I learnt how to develop and print by watching him. He was printing from his bedroom in a small place and his bed was full of books and camera equipment. He was the one who encouraged me to start printing in my room. I copied that from him.

Tell me how it all started for you in photography.

Before my Ever Young studio was set up, I was an apprentice with a relative, JP Dodoo, and I did a lot of developing and printing for friends, as well as taking photos. I called my company FS James Barnor’s Quick Photo Service — FS are my initials, for Frederick Seton. If you bring me the negatives, you will get the photos the next day. It was a makeshift studio, a small space. Once I saved up some money, I opened my Ever Young studio. Serving as an apprentice, you do a lot of retouching on the negative plate. This was before sheet film was introduced.

Centre of things: James Barnor opened Ever Young studio in Jamestown, Accra, in 1953. The lighthouse and Fort James are on the left and his neighbours were the Sea View Hotel and the Weekend-in-Havana nightclub (James Barnor/Autograph ABP)

They were starting an English newspaper press. Cecil King was the chair of the Daily Mirror [in London] and he brought Hugh McClelland with him to recruit a photographer. They went to Dodoo as the popular studio photographer in town and asked him if he would like to work for The Daily Graphic, which they were setting up. It was not his thing. He referred them to me. I showed them my work. “Not quite,” McClelland said, “but we will train you.”

So, from 1950 to 1953 I was a photojournalist with The Daily Graphic.

When Nkrumah was released [from prison in 1948], he went to the arena about 150m from my home. I ran to the place and held the camera high above my head. I looked through the viewfinder and took two pictures. The next day I was selling the prints at the market. I made a big print and hung it around my neck to advertise the image.

I was doing groups and weddings. I was taking pictures at dances and concerts.

I was close to the music fraternity too. I knew ET Mensah, who studied under TJ Lamptey, a music master. Mensah was a pharmacist, but played the trombone and the sax and spearheaded high-life music before all the others. I knew all the musicians. I was taking their pictures.

I did everything that came my way. I put an advertisement in the newspaper for people to learn photography from me. You know, for apprentices. In the same way that I learnt, I was advertising to teach others.

You worked for Drum in Ghana in the 1950s?

Drum Nigeria was started before Ghana, and when Drum came to Ghana they came to me. Anthony Smith started the Drum office in Ghana, and he had Ghanaians working under him, including a business manager. Henry Ofori was one of the remarkable journalists who worked there. I worked with Henry Thompson at the end. There were other photographers too. I had the Ever Young studio at the same time so I didn’t care about that [the competition]. I had easy access to the politicians. When I had some pictures of interest I would sell them to Drum. Smith came and spoke about our relationship when my exhibition opened at Autograph ABP in London.

Could you describe your relationship with Bailey?

I was very close to Bailey and whenever he visited the Drum office in Ghana he stayed at the hotel close to my place. We had night beach parties, something I never thought of doing before. It was Jim Moxon, public relations officer for the government of Ghana, Bailey, others and myself. Girls and boys. Once we even had a party in my studio. I had to borrow a radiogram. Bailey told me stories of how he was drinking with Nelson Mandela in the shebeens in Johannesburg. They knew each other well. Bailey bought a motorbike and kept it in my office and we rode together whenever he visited Accra.

On the eve of Independence Day in March 1957, Bailey came to see me and asked, “What are you up to?” “I’m going to bed,” I replied. He said, “Come, take your camera and let’s go.” We walked to the Accra polo grounds, opposite Parliament House. Nkrumah was addressing a crowd, saying, “Ghana is now free!” I took pictures that night and sent them to Drum in South Africa.

In England I used to go to Peterborough to stay with Bailey’s sister-in-law, Cecile. She organised for the directors of Agfa to come there so that I could meet them. She helped me a lot.

When Bailey was knighted by the queen in London, his wife — I think it was Barbara — invited me. And when Bailey died in South Africa there was a service for him in London and his wife and son came. Cameron Duodu, the Ghana editor, was there too.

Could you describe the scene in your Ever Young photo studio in Accra from 1953 to 1959? What would happen?

I, or somebody working for me, would receive the person. Most people would not make appointments. There was always music in the background. There was the Sea View Hotel next door and the Weekend-in-Havana nightclub nearby, owned by a Nigerian. Ghanaian bands would go to Nigeria and Nigerian bands would come to Ghana.

People would drop by my studio. Around the corner was Fort James. The port was active. Lorries going up and down; everything that was happening in Accra was passing through my small street. My studio overlooked all of this. People would come for passports, studio photos, whatever.

I’d take your name and then you’d pass into the studio. One part was for sitting and one for the store or reception. People would wait, sitting on chairs for their turn. I had a stage one foot off the floor, with different backgrounds: one painted on the wall, one painted on cloth on a wooden pole to be rolled up and put away when not in use.

That’s what my uncle, the photographer, and everyone used to do at the time. We used chalk to dab people’s faces down when they were too shiny. If you were automatically photogenic, I would take more than one photo. Women liked full-body photos with shoes, a handbag and their accessories. Men liked the boss image. For them I would take a three-quarter or half crop.

The photos that are now on display at my exhibition Colors in Paris show the whole image; they reveal the boxes, etcetera that I would have normally cropped out in my studio at the time. Good photographers crop from their camera because they know what they want. While I was taking the photos I’d communicate with the sitter. Some sitters were not photogenic but then you do the best that you can afterwards, with touching up, et cetera.

I liked doing studio photos as well as photojournalism when I was going out on to the streets with my camera. Those pictures would go out into the wider world, not only stay on walls and in photo albums.

When I was going to London I contacted Bailey and he said to me, “I need you in Accra, not in London.” Then he said I must keep the Ever Young studio going while I’m away. Ghana was planning a television channel, which is what made me go to London. I was preparing for television.

The second part of this interview will be published next week