Hlaudis congregants: Defenders of Hlaudi Motsoeneng (some ANC members and others belonging to the SesKhona Peoples Rights Movement) protesting in support of the SABC executive. (David Harrison)

‘I want to applaud people who recognise this wonderful person called Hlaudi. Because when I came here there was no SABC. People who work here will tell you there was no SABC. When I came here, there was just a disaster … I believe that everywhere where I am, I do miracles and I’m going to do those miracles in the position I’m going to occupy.”

Thus spake Hlaudi Motsoeneng, not long after the Supreme Court of Appeal had denied his leave to appeal against the high court judgment that he was unfit for the job of the SABC’s chief operating officer (he was rehired as group executive of corporate affairs), and a week after the SABC had posted a loss of R411-million.

That was in 2016, two and a half years after the report of the then public protector, Thuli Madonsela, into the state of the SABC, titled When Governance and Ethics Fail, had appeared — and six months before he finally left. Having lied about his matric results, as famously noted by the public protector, he rose swiftly to the top, in an ascent he could not have accomplished without the support of then communications minister Faith Muthambi and the favour of then president Jacob Zuma.

From regional acting editor (Free State and Northern Cape) Motsoeneng jumped to executive manager of stakeholder relations in 2010; then, a year later, he was made acting chief operations officer and, in 2014, after some conflict, he was confirmed as permanent chief operations officer. He repeatedly gave himself huge salary increases, as well as bonuses of up to R11-million for deals he made with other broadcasters that were, in reality, disadvantageous to the SABC. He put much effort into the founding and funding of the Guptas’ TV station, ANN7.

When he was chief operations officer, he made himself editor-in-chief as well, a move most journalists would consider unethical, and there followed an era at the SABC that was dubbed The Madness of King Hlaudi. Apart from such vainglorious embarrassments as the “thank you Hlaudi” song by Mzwakhe Mbuli and choir (commissioned), Motsoeneng declared a quota of 70% good news and 90% local content, which basically ruined the SABC financially. It has been teetering on the brink of collapse ever since.

Motsoeneng’s attempts to twist the news and opinion at the public broadcaster included the instruction that violent protests and those involving the destruction of property should not be shown, purportedly because that encouraged the protesters to burn things down. It was to this diktat, as well as a new editorial policy Motsoeneng couldn’t quite manage to promulgate properly on the SABC’s intranet, that the journalists who became known as the SABC 8 objected.

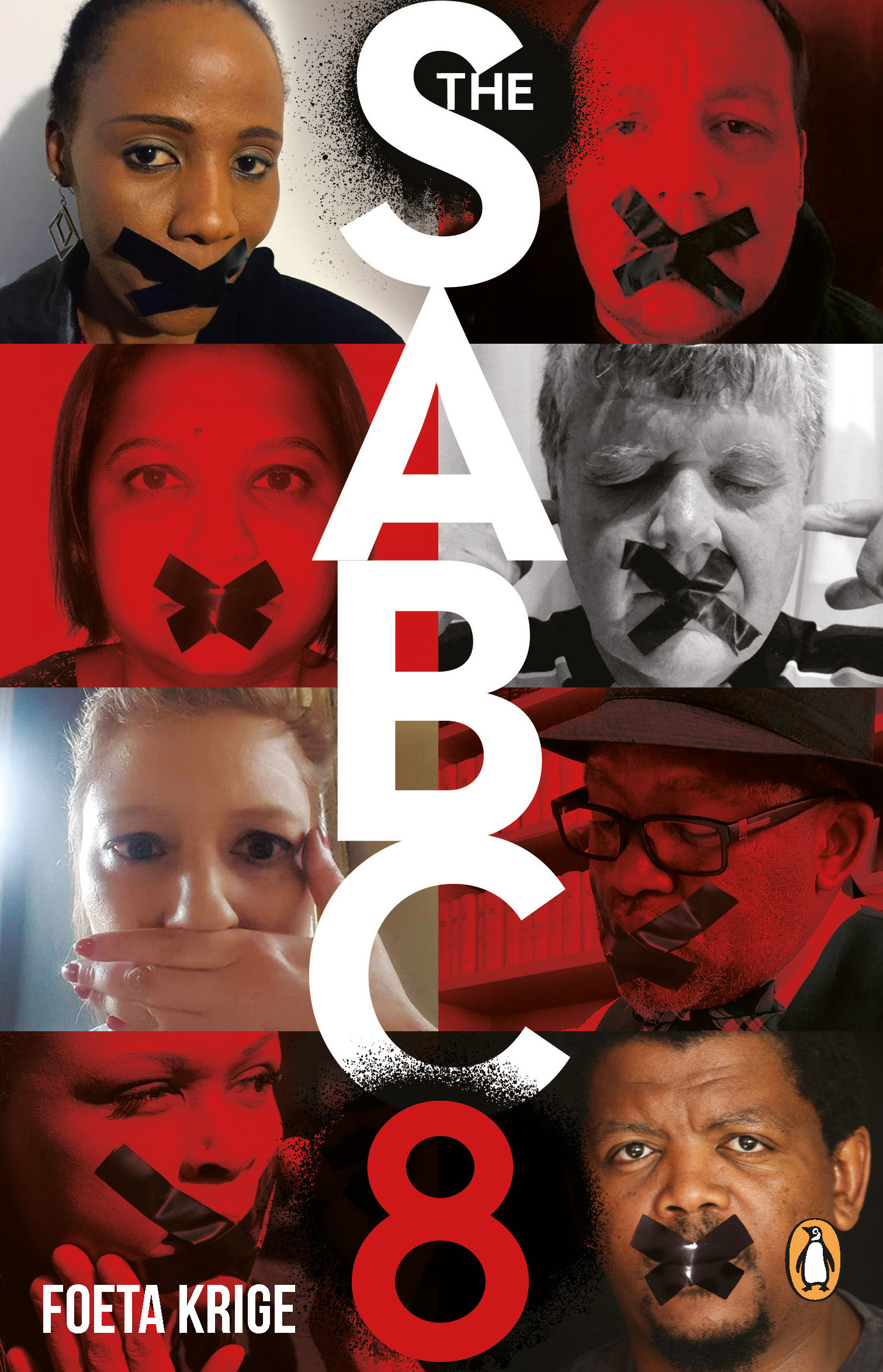

Those journalists were Lukhanyo Calata, Thandeka Gqubule, Foeta Krige, Busisiwe Ntuli, Krivani Pillay, Vuyo Mvoko, Jacques Steenkamp and Suna Venter. Because of their objections to Motsoeneng’s unethical policies and intimidatory tactics, they were harassed and ultimately fired. They had to fight for their rights, the rights of all journalists to tell the truth and, in fact, the right of a democratic nation to have an impartial, informative national broadcaster.

This book by Krige (who came from the radio side), gives a full account of their ordeal as they tried to defend the principles of honest journalism against the propagandists and functionaries of state control. A long series of legal battles followed, as meticulously documented by Krige. He also records, interestingly, some of the divisions that developed among the eight, partly in response to the role played by the Solidarity trade union, which appeared to have a “white rights” agenda as well. He also details his personal and family views and experiences as they went through this “cold, dry season”.

The eight would ultimately win in court, but in the middle of it all Krige’s tale morphs into a horror story, with death threats from unknown phone numbers (and one attempt to bribe lawyer Aslam Moosajee), break-ins and a trashed flat, shots fired at SABC8 members, and even a bizarre abduction.

Venter, already suffering from mercury poisoning, and clearly the most volatile and vulnerable of the group, was basically hounded to her death. When Krige took a second set of tyres that had been slashed for analysis, he was told it was not the work of an amateur.

The parliamentary hearing that eventually took place in December 2016 at least took seriously the SABC8’s submissions — and they are sterling statements of journalistic integrity and honour, as well as brave warnings about the kind of destruction a Hlaudi, even a sane one, could wreak at an institution supposed to be serving the people of a free, democratic South Africa.

In contrast, Muthambi and the last remaining nonexecutive board member (the rest having resigned) told the committee they were unaware of any problems whatsoever at the broadcaster, and endorsed the diktats of Hlaudi. The board member could only vaguely recall who the SABC8 were; he said he’d heard about them on the radio — not, obviously, SABC radio.

The parliamentary ad hoc committee endorsed the views of the SABC8, and indeed apologised to them for the pain they had gone through in the service of truth. It recommended that Muthambi be removed from the job of communications minister, and she duly was. Motsoeneng was dismissed too — but not until he’d had a last fling, staging a self-congratulatory press conference that demonstrated only that all his delusions were intact.

A new board was set up, and it began to grapple with the sorry state of the national broadcaster. It is still battling. The SABC8 may have won their own victory, but, as Krige notes, there is still considerable doubt as to whether the SABC itself can actually survive.