(John McCann/M&G)

‘For it is not the light that is needed, but fire. It is not a gentle shower but thunder. We need a storm and we need earthquake, that is what Eskom needs”.

It was with these fighting words, quoting abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass, that departing Eskom chief executive Phakamani Hadebe delivered his last set of results at the power utility. The parting shot was apt — Eskom is in dire straits, as the dismal figures for the 2018-19 financial year showed.

With losses of almost R21-billion, an almost 2% drop in electricity sales and debt servicing costs that far outstrip its ability to pay them, Eskom is indeed in need of some resounding thunder.

Jabu Mabuza, Eskom board chair and now acting chief executive for three months, told the Mail & Guardian, with Eskom’s power plants under so much strain, together with its financial difficulties, that: “There is no tolerance, there is no buffer, there is no margin for error”.

But for Eskom to turn its financial corner, four key issues need to be addressed according to Mabuza.

The process to separate Eskom into three separate business units must begin; Eskom must contain its costs; its ailing revenues must be addressed — both in terms of collecting outstanding municipal debt and achieving what it deems cost-reflective tariffs; and, finally, its needs to address — as of July — its R447-billion debt millstone.

All four matters need to be addressed “or the model breaks”, Mabuza said. And this needs to happen against the backdrop of an electricity system that, as Eskom chief operating officer Jan Oberholzer has described it, is “unpredictable” and “unreliable”.

“If for whatever reason we can’t get cost-reflective tariffs or we can’t collect municipal debt … whether its because of politics or sociopolitical issues, or we cannot contain our costs — whether it’s because … in coal procurement there is an issue or on the headcount we cannot realise those savings … it is going to be a problem,” Mabuza said.

Eskom’s debt-servicing costs have ballooned in the past financial year, rising to R69-billion — including both interest and capital repayments. This figure dwarfs Eskom’s cash from operations of about R33-billion. The outlook for the current 2019-20 financial year is little better, with debt-servicing costs expected to rise to R84-billion.

As well as the power utility’s debt-service costs, other key costs have increased, namely primary energy, which rose by 17% to R99-billion. This was thanks to a marked increase in the use of open-cycle gas turbines — those owned by independent power producers, as well as Eskom’s — in a bid to keep the lights on after intensive rounds of stage-four power cuts earlier this year. Staff costs also increased, despite a minor decline in headcount due to natural attrition, with salaries and benefits for employees rising 13% to R33-billion.

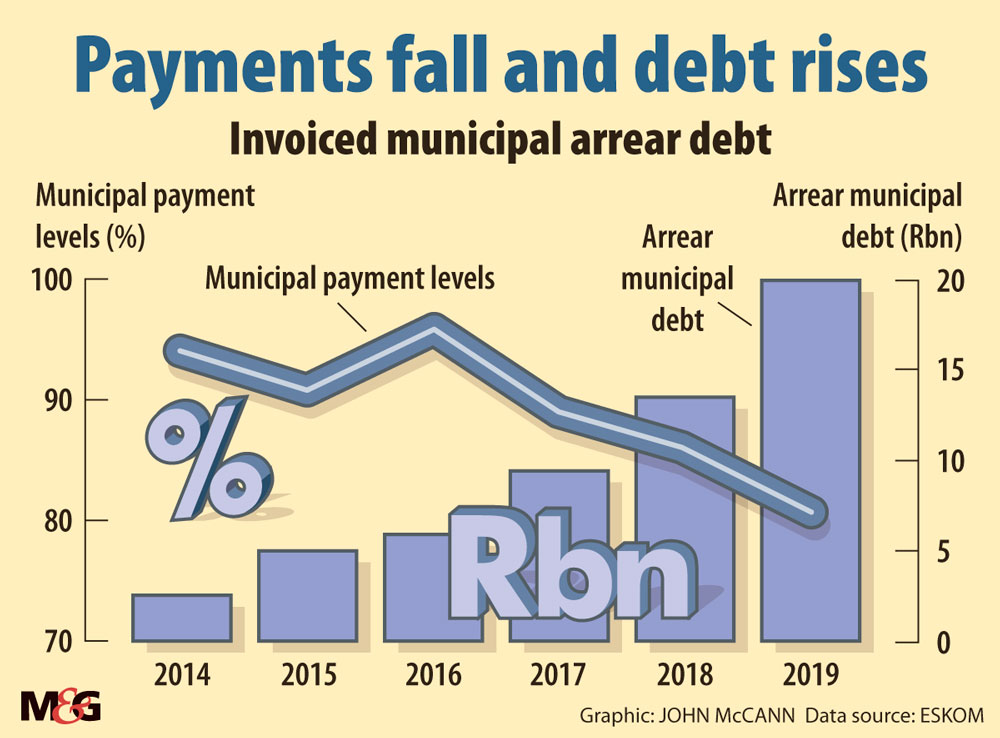

Meanwhile, debt owed to Eskom by municipalities and Soweto residents has risen to R19.9-billion and R18-billion, respectively.

Despite extensive criticism of its position, Eskom maintains that tariffs are not cost reflective and is taking the national energy regulator on over several tariff decisions.

So while costs have risen in double digits, revenues rose a mere 3% from the previous year.

But in the face of all these challenges, Mabuza pointed to the work that is beginning to try to turn the ship around.

To start with, Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan announced the creation of an office of the chief restructuring officer to be set up by Freeman Nomvalo, the chief executive of the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants, and a team from the accounting body.

There had been initial confusion around the chief restructuring officer’s term, but the public enterprises department clarified that Nomvalo is expected to head the process for six months — and the work will focus mainly on efforts to restructure Eskom’s balance sheet and deal with its debt load.

At the same time, Gordhan promised the delivery of a policy paper on the separation of the utility into its three business units — generation, transmission and distribution — by September, a process first outlined by President Cyril Ramaphosa in his February State of the Nation address.

Some analysts, however, remain sceptical how the role of the chief restructuring officer will now work.

“There is no sense this is an empowered position to push forward radical change and [it] sounds like death by committee,” Peter Attard Montalto, the head of capital markets research at Intellidex, said in a note. He expected it would take nine to 12 months before a preferred debt restructuring option is presented to the government, with its execution taking another six months.

The chief restructuring officer’s office will report to the public enterprises and finance ministers, arguably creating a recipe for contestation and confused accountability.

But Mabuza did not see it this way. “Once there is role clarity and mandate clarity and there is proper delineation of who should do what, and when … there should be no issue,” he said.

The chief restructuring officer’s work is “fundamentally a restructuring of the balance sheet”, he said. It has never been done at this scale at a state-owned enterprises level he said, adding that the process is “still evolving”.

Ultimately, however, it was clear that accountability lies with the Eskom board, said Mabuza.

The process of separating Eskom into three separate entities is likely to be an even more fraught one. Labour unions have expressed their antipathy to the unbundling as it is viewed as little more than an opening for the privatisation of Eskom’s assets and job cuts.

Eskom’s rising wage costs and declining productivity levels have been a key focal point for critics, who point out that reducing headcount will help curb costs. But Hadebe indicated at the results briefing that the president has asked Eskom to refrain from retrenchments.

Mabuza said that he has approached Eskom’s labour unions to set aside a whole day to discuss ways to address Eskom’s challenges.

Eskom’s leadership has views on how these should be fixed, Mabuza said. “We have put those to the shareholder; we are continuously putting those to the funders,” he said. “We need to put those in a manner that is fully appreciated and understood by labour.”

Although he acknowledged that benchmarking exercises comparing Eskom to similar utilities in terms of staff productivity showed that Eskom was not “efficiently resourced”, wholesale retrenchments are “not a silver bullet” for Eskom’s problems Mabuza said.

The company is working to reduce its wage bill in other ways — such as through natural attrition, voluntary severance packages and early retirement. But against a backdrop of unemployment levels rising to 29%, Mabuza said he understood the president’s position.

But despite these incremental steps towards change, there are expectations that next year will be just as bad for Eskom. Debt-servicing costs are expected to rise to R84-billion in 2019-20, compared to R25-billion in cash from operations, with another R20-billion in losses forecast. Faced with these numbers and no margin for error, Eskom will need fire and thunder aplenty.