(Illustration: Adam Carniege)

BODY LANGUAGE

I was about nine years old when I first experienced pussy grabbing. I was feeling unwell, had been vomiting and, with a high fever, was feeling lethargic and out of sorts. My mother took me to see a white doctor in the southern suburbs in Cape Town. I went into the doctor’s surgery alone for the examination while my mother waited in the reception area.

After doing the usual sort of thing such as listening to my heartbeat and looking inside my mouth, the doctor explained that he would need to examine every part of me. He then slid my panties aside and inserted his fingers into my vagina.

I do not recall anything other than the fact that I trusted in his authority and had no reason to believe that anything untoward had happened. I thought he was just doing his job and looking for viruses. In my innocence, everything was as it should be.

Ten years later, still wrapped in my cloak of innocence and blind belief that nice white doctors could not possibly engage in acts of sexual violence, I went to see a gynaecologist. I was about 18, and in desperate need of resolving the misery of the thrush that established itself in my nether parts.

So off I went to a gynaecologist in Sea Point. After a lengthy “chat”, during which he asked me all sorts of personal questions, he told me to undress and get on to the examination bed while he waited in his office.

I took off my clothes and lay there, worried about the foul business going on in my vagina. Luckily, the doctor seemed nonplussed and chatted away while examining my breasts and doing my pap smear. With an approving eye, he told me that I had a nice body and asked how I managed to keep it in such good shape.

While I had a sense that there was something about him that I did not like, I trusted him completely. Eventually, he told me to get dressed and that I should join him in his office when I was done. I waited for him to go and I took my naked self off the examination bed and walked towards my clothes.

When I was halfway across the room, the door opened, the doctor came back in, with a “Sorry, sorry, I forgot to check something”. I was made to get back on to the examination bed. I was mortified. He had caught me naked and vulnerable, and I meekly resolved to do as he had instructed. It did not cross my mind that I could challenge him.

I duly got back on to the bed and lay back while he, without gloves, proceeded to probe me with his fingers, looking inside my vagina. Something about it felt wrong, but I was far too trusting to think that he had any ulterior motives. He was the white doctor who would do what he thought best; I was the inexperienced young girl and my job was to believe and trust in the process.

Yet, I left his surgery with a niggling sense that I had been violated, without having the terms of reference to structure these thoughts. Nonetheless, my thoughts lurked in the depths of my consciousness.

A few years later, I dabbled with witchcraft and feminism. The witchcraft was not so much for me. It was only fun when I thought it was about drinking your period blood and running around naked under a full moon. But the feminism kick-started a deep introspection, one in which I retracted to a place deep in my core to engage with everything I thought I knew.

This journey was not just an intellectual one; it was quasi-spiritual too. I then catapulted myself outwards to look at the world around me and began to ask questions about how we as people, as communities and societies, forged relationships, about how we engaged with each other and how the notion of power came into play.

I realised, with a sense of shock, that I had never claimed agency. I had never felt entitled to. My background and the sociopolitical context in which I had been raised geared me towards being respectful, silent and a follower. It was both frightening and liberating to discover that my views mattered, that they need not conform and that I had a responsibility for staking claim, for speaking out and taking up space in the world, very different from my attempts to shy away, hide and silence my voice.

I could diverge from the orthodox pathway and create new routes of my own; I need not follow, but instead, could dare to think about leading the way. Suddenly, I was reconceptualising my experiences through the prism of a gendered social order, in which there were gendered interactions and power dynamics at play that determined how I was able to fit into the world and claim agency.

Even more startling was the fact that these gendered interactions were taking place not just at an individual level, but at a societal level: they affected every social and public institution that I engaged with.

And, finally, I was able to view my interactions with my childhood doctor and the gynaecologist through the lens of sexual violence and its underlying power dynamics of established, affluent white men of the patriarchy doing what they did because they could.

It is almost 30 years since I began my journey as a feminist. And here we are, at a juncture where arguably the most powerful nation in the world has elected to its highest office, a man who endorses pussy grabbing as a legitimate means of exercising control over women. US President Donald Trump was in office for a heartbeat, and he already showed signs of how his administration would have a significant effect on the lives of women all over the world.

And yet, Trump’s first week in office also gave me tremendous hope. Women across the globe decided, “Hell no, not under our watch!” United in a mission of challenging institutionalised patriarchy, hundreds of thousands of women took to the streets across the globe in a surge of unprecedented social mobilisation. Cities around the world were alight with women fighting back.

And the message is abundantly clear — there is a place for being a nasty woman when we need to be, “not as nasty as a swastika painted on a pride flag … not as nasty as racism, fraud, conflict of interests, homophobia, sexual assault, transphobia, white supremacy, misogyny, ignorance, white privilege” but nasty like “the battles my grandmothers fought to get me into that voting booth”.

If the past few months have taught us anything, it is that we will not take misogyny lying down. As women, we have agency and we will continue to find ways of claiming this and taking a stand, all in the name of making the world a more peaceful, tolerant and non-nasty place for all.

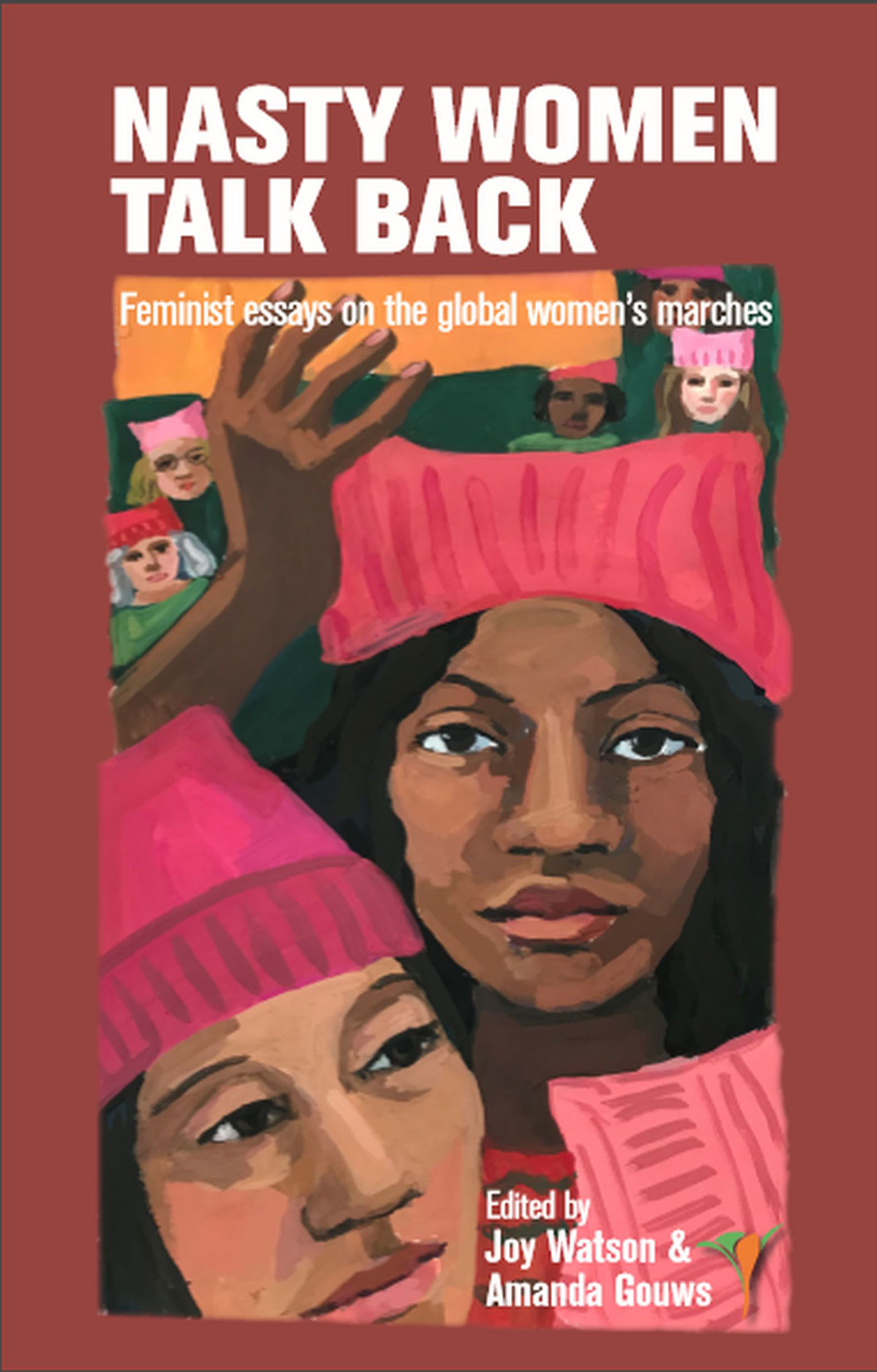

This is an edited version of the story Pussies are not for grabbing! by Joy Watson from Nasty Women Talk Back: A Collection of Feminist Essays Inspired by the Global Women’s Marches, edited by Watson and Amanda Gouws