Esther Cenga moved from the Eastern Cape to Worcester in 1954 where she cleaned white families homes. She forgot her bad experiences until Shoprite was bombed in 1996 by right-wingers, killing four people and maiming 67. (Botswele Mogotlane)

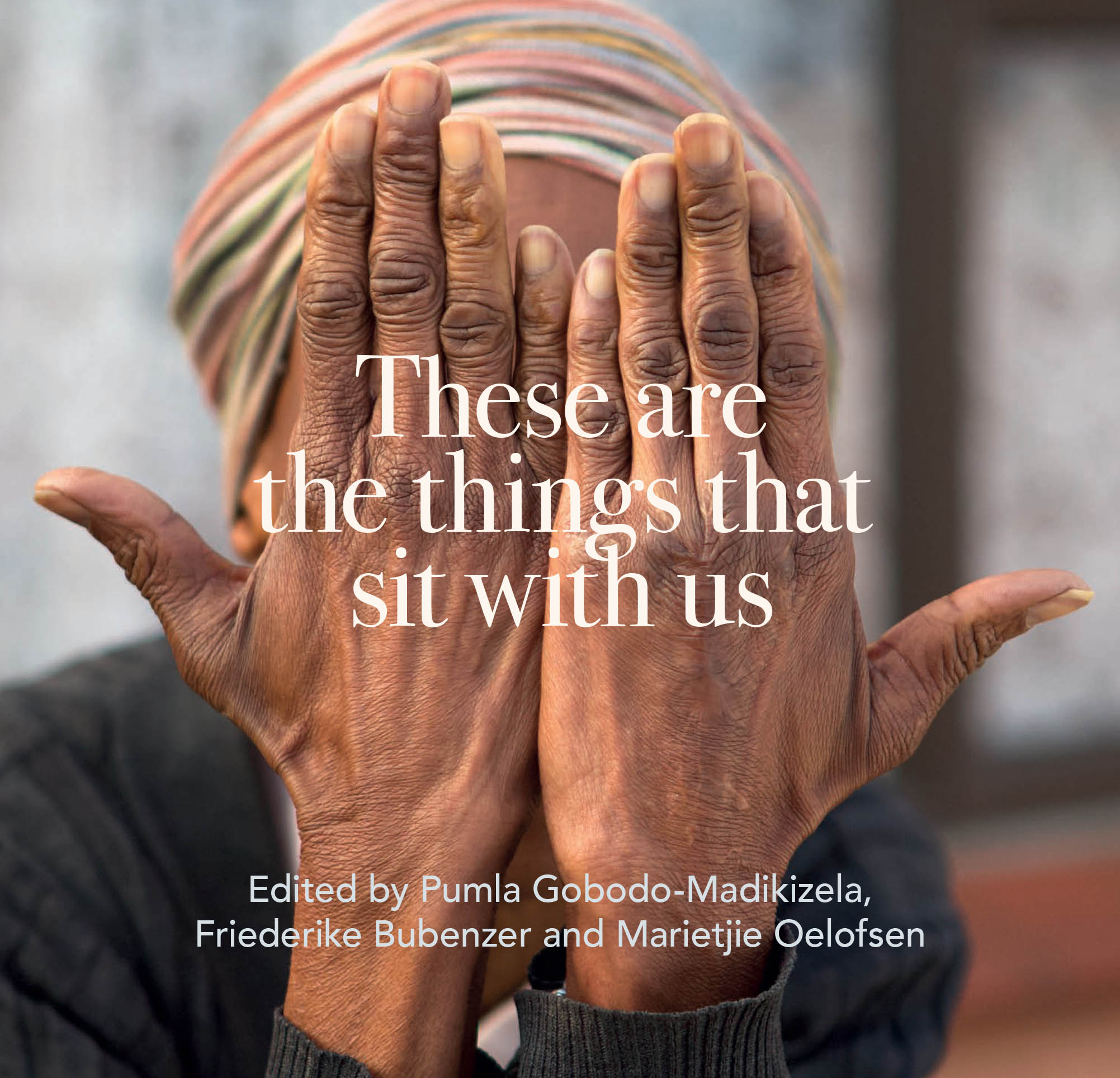

A drafty 1970s town hall in the Boland would not be where one would expect an electrifying evening of interracial discussion on a cold winter’s night, but that is exactly what happened on a recent Thursday in Worcester. Something unusual and urgent emerged as residents gathered for the launch of the book These Are the Things that Sit with Us, edited by Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela and Marietjie Oelofsen, of Historical Trauma and Transformation at Stellenbosch University, and Friederike Bubenzer, of the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

The honest and highly charged dialogue between storytellers from the book and the audience revealed a vital broader need for cross-racial and cross-generational conversations about the past.

“It’s the elephant in the room,” storyteller Russell Cupido said. “This silence sits between those who suffered and those who benefited throughout the country; through all the pain and the hurt we must now begin to speak to each other.”

Juan Karriem, whose account of enduring inner battles with harrowing memories is in the book, said: “I hid my history from my children, not wanting to infest them with my prejudices. But tonight I brought my daughter along to see the book for the first time. South Africa is indeed a traumatised nation. We need to have these uncomfortable conversations.”

The book that inspired such honesty documents everyday experiences of South Africans in Langa, Bonteheuwel and Worcester during the country’s brutal past. It’s a compelling and important read, opening up an opportunity for the wider public to bear witness to what it means to have lived through apartheid. The 29 vignettes were selected from a four-year research project examining intergenerational repercussions of historical trauma.

Kholeka Klaas and her family were removed from Cape Town to Langa. Her brother was political: ‘We often had knocks at the door when the police came …’. (Botswele Mogotlane)

“We wanted to understand the relationship between what happened in the past and what happens today,” said Gobodo-Madikizela in her opening remarks. Citing the profound moments of change and transformation that she witnessed while serving on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, she said people needed new spaces where listening to each other’s stories could bring us back to a place of hope.

The stories appear in the three languages spoken by the storytellers — isiXhosa, Afrikaans and English — offering the reader the opportunity to listen to the story in the teller’s mother tongue and the rich layers of meaning. At the Worcester launch, it also paved the way for unfettered cross-language discussion, facilitated by Gobodo-Madikizela. In a country where language still causes such division, this was refreshing.

The quiet, insistent life of the narratives brings a pervasive struggle with memory to the surface that is part of the inner life of millions of South Africans of colour. When a son tells of his vivid recollection of seeing his father being stripped of his land, his livelihood and the dignity of being able to take care of his family through forced removals, or a woman tells how her future was cut short by a bomb blast that devastated her family, or an older man with a deeply lined face and gentle eyes describes his enduring sadness at the lack of opportunity to study further, we know that these stories could have been drawn from just about anywhere in the country. They give voice to a larger narrative of collective historical memory that is raw and alive under the surface.

Phillip Voegt is a District Six child and remembers the forced removals. ‘Ek het wit mense gehaat.’ It took him many years to get rid of the bitterness. (Botswele Mogotlane)

Despite the recounting of haunting experiences of loss and humiliation caused by apartheid, this book expresses much more than feelings of suffering and victimhood. Look deeply into the eyes of any one of the men and women in the arresting photographs accompanying the stories and you will recognise the remarkable generation of people you encounter every day in the streets, at work, in malls, in taxis, in homes. What these stories speak of, above all, is the extraordinary resilience, dignity and strength called up to survive and build lives from the chaos of apartheid, even as, for most people, their life circumstances remain unchanged 25 years after democracy.

And what about the voices of those whose identities were shaped in white culture and who have to find their place somewhere on the spectrum of perpetrator, collaborator or, at the very least, beneficiary of the system that caused so much pain and destruction? The stories of Worcester’s white residents sit awkwardly in the book. How could they not? The differences in social and economic circumstances, in frame of reference, in understanding and experience of suffering are as evident on the page as they are in the world around us.

But these stories are vital to any project linking the past with the present because they begin to fill the uncomfortable interracial silence between South Africans, “the elephant in the room”, as Cupido called it. Sentences like “I have not really experienced anything traumatic,” and “If I did not have the opportunity to go to a good school, I would not have been where I am today,” and “What can I do to change their scenario?” are a necessary part of the discourse.

If we strive for any kind of healing of the fault line in our collective consciousness, if we want to reach a place where the boundaries of “us” truly extend through this fault line, we’ve got to work with what is real. For one of the storytellers, Hilton van Wyk, reality included “something that I can’t explain” that came up in him when he saw white people. “I am cross, sad, violent in the way I think. And that makes me quiet,” he said. “I don’t have the strength to be violent, but I feel violent. I am looking for a way to understand people.”

The articulation of stories, which can connect people at the deepest human level, seem to be a good place to begin to foster such understanding between races and generations. As Karriem’s daughter said, after reading her father’s story and hearing him speak: “It’s a big thing for me to be here tonight for my father. This will help us to understand him so much better.”