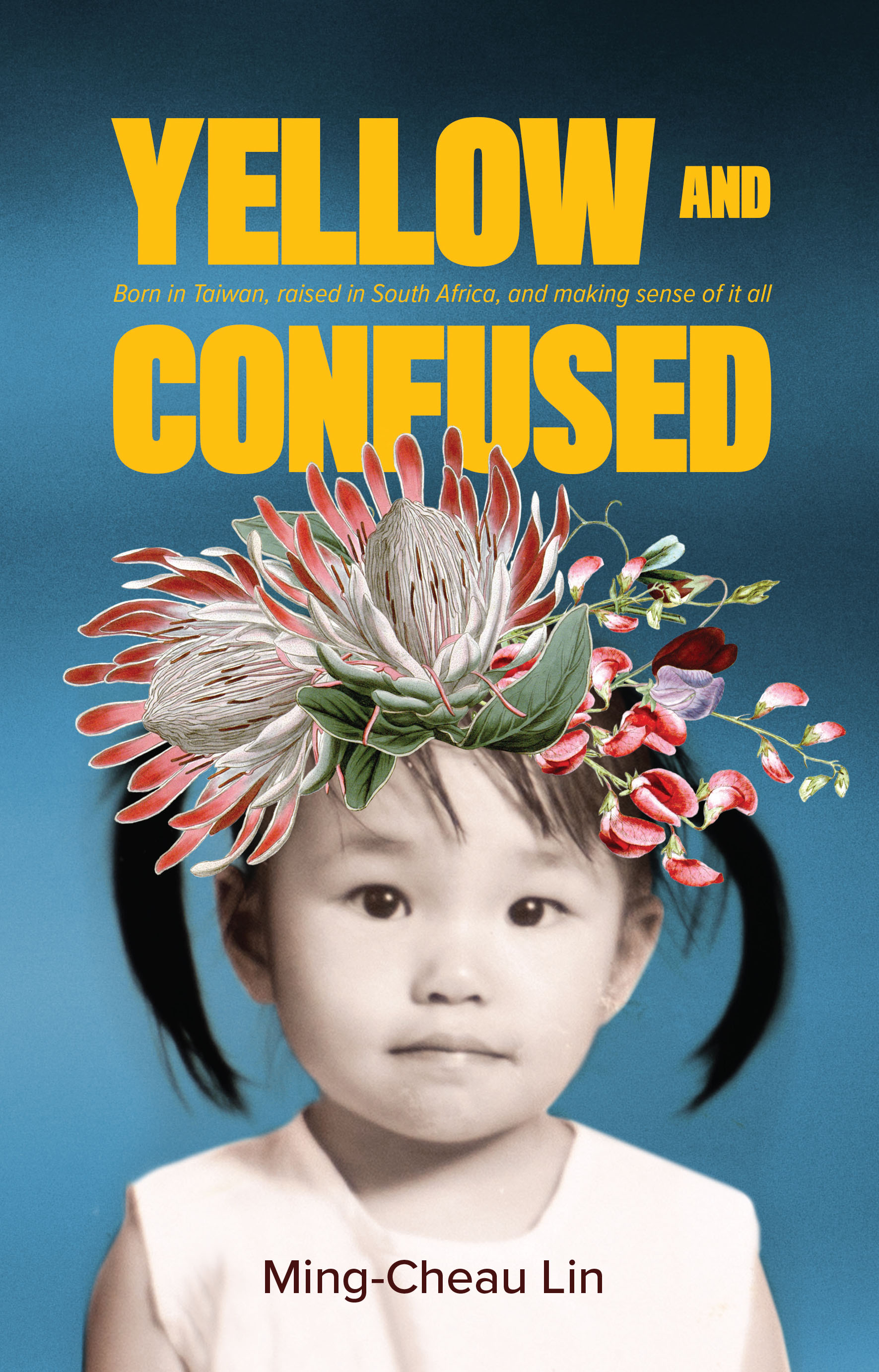

Challenging stereotypes: Author Ming-Cheau Lin has recently published her memoir, Yellow and Confused, in which she reflects on her experiences growing up as an Asian South African. (Grethe Rosseaux)

The typical introductions occur when I meet someone new. They want to know where I’m from and I want to say Bloemfontein because that’s where I grew up but I don’t. I say Taiwan, because after years of practice I know that’s what they want to hear. And once I say Taiwan, I know what the follow-up remark will inevitably be.

“But you speak such good English!”

To the majority this might seem like a compliment or even a simple pleasantry, but as an Asian who grew up in South Africa and who only ever attended school in South Africa, I think to myself, well, I should speak “good English”. In fact, I also speak some Afrikaans and a little Sotho, which were school subjects, in addition to my home languages. And I’m by no means impressive or unique — there are many other multilingual South Africans, after all.

Why can’t your first impression of me be as a South African, and not a foreigner? You don’t have to ask every Asian person you meet: “Where are you really from?”

Now that we’ve cleared up why I don’t have an “Asian” accent, my next question is: What is an Asian accent anyway? Is it the accent of the old Asian man from a 1980s or 1990s American martial arts film, directed (and sometimes played) by a non-Asian person? Has it never occurred to you that “Asian” is continental and not a language? Or that every Asian language might have a different accent? And when you hear what you’d probably describe as “broken English”, shouldn’t it occur to you that the multilingual speaker is trying their hardest to communicate with you in English because English is the only language you speak? Does that person deserve mockery for their efforts?

And while we’re at it … No, I probably don’t know your Asian friend Sally or John, because I’m from Bloemfontein and they’re from East London — where you’re from. I mean, imagine one of us asking you if you know our high school friends Natalie and Mareé because they’re also white.

And no, “ching chong cha” doesn’t mean “rock, paper, scissors”. In fact, it doesn’t mean anything. And guess what — you’re not the first person I’ve met who’s made “that” Asian joke.

Is it any wonder I’ve become so negative over the years? My skin tone classifies me as “Asian” and I call myself an Asian South African. Yes, I was born in Taiwan and my family moved here when I was three, but all of my childhood memories are of growing up in a small townhouse in Helicon Heights in Bloemfontein.

We settled here in the early 1990s, along with more than 2 000 other Taiwanese immigrants. My family came for better opportunities, incentivised by the old government to grow and develop the local manufacturing industry. My parents worked hard to provide us with the opportunity of tertiary education but even with that privilege I struggled to have a “normal” childhood. I struggled to understand why people treated us like we were beneath them. Because of how I looked, I struggled to blend in. And I struggled to understand why it was that way.

I remember at school I played a piano duet with an Afrikaans girl and I liked her, she seemed nice. Three years later, this same girl took offence to me calling her out for bullying another yellow girl. I told her to stop her nonsense and she retaliated by yelling at me in anger, “You ching chongs are disgusting and weird! Your people pray to a statue, you eat dogs and you have ugly squint eyes.” I tolerated it calmly — I asked her if that was the best she could come up with — but that experience of racism wasn’t even unusual. Almost every second-generation Asian in South Africa has had a similar one. Today, I know I can report a racist incident like that, but back then we were conditioned by our community to tolerate the hatred. We didn’t want to stand out as troublemakers.

Filling out government or work forms where the only tick-boxes available are “African”, “coloured”, “Indian” and “white”, we are told to tick the “coloured” box. Or we are included as another category — “other”. Literal “othering”. We are not made to feel included in this delusion of a “rainbow nation”.

The term “Asian South African” is largely and locally defined as Indian but, as we’ve seen, Asia comprises 48 countries. Most Asians who grew up in South Africa have been on the receiving end of the same type of discrimination. Not that my parents didn’t try to fit in.

They were taught English at school in Taiwan but just the basics, so a fluent, deep conversation was a rare occurrence. Being in the manufacturing business, my papa’s English improved as a result of regular exposure, whereas my mama didn’t get the chance. The sad result is that locals weren’t patient with her; I observed this often in their behaviour towards us. As a child, it’s incredibly hard to see your parent sad and feel powerless.

I remember us buying new bedsheets the one time. The woman my mama approached just rudely gestured for her to go back to the section she came from. When my mama tried to explain otherwise, she rolled her eyes and spoke to my mother like she was an annoying child. I was livid that someone could treat another human that way. My mama would rather avoid a scene but I was left confused and angry.

It’s difficult finding your way between two cultures, but how is it fair that we should accept norms that aren’t normal to us?

This is an edited extract from Yellow and Confused by Ming-Cheau Lin, published by Kwela. She is also the author of Just Add Rice (2018) and runs a blog, butterfingers.co.za