For the first time Ernest Mancobas art and thoughts were celebrated in Paris (Bertel Bjerre)

Invisible in France and not recognised enough in South Africa, South African artist Ernest Mancoba’s art and thoughts were celebrated for the first time in Paris in a retrospective exhibition entitled I Shall Dance in a Different Society at the Centre Georges Pompidou from June 26 to September 23.

I visited the exhibition on three occasions: once with curator Alicia Knock, once for the talk and performances, and the last time was on the eve of its closure. It was not enough. Each time I saw something new, whether it was the wide assemblage of Mancoba’s work from public and private collections from around the world, the works of Kemang Wa Lehulere interpreting the artist, or the film footage by Man Ray of a highly prized African art collection.

From Mancoba’s earliest carvings in wood, to ink drawings, to the figurative abstract and abstract figurative paintings on canvas, with less and less paint as the years went on, to the linocut prints and lithographs, and finally the abstractions in ink and watercolour and the coded alphabets on paper, we follow the artist’s trajectory from his time in Pietersburg (1920-1924, where he trained as a teacher) to his final days in Paris.

On exactly the same dates an exhibition on the work of Sonja Ferlov Mancoba, curated by Jonas Storsve, ran concurrently on the same 4th floor of France’s renowned modern art museum, just a few metres away.

Born in 1904 in Boksburg, outside Johannesburg, Mancoba died in Paris in 2002, living through the full 20th century of modern and contemporary art movements, two world wars, the Cold War, and much more.

The two artists met in Paris in 1938 and were married in 1942, when Mancoba was interned as a British subject — South Africa was still a British colony at this time — in a German prisoner of war camp during World War II. Their son Marc (also known as Wonga) was born in 1946, and in 1947 they moved to Kattinge, near Roskilde in Denmark. There they were part of the CoBrA (Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam) art movement (1948-51), an avant-garde group initially formed in Paris, inspired by the spontaneity of children’s drawings and freedom in line and colour.

After some disappointments with the group they returned to France in 1952, to Oigny-en-Valois, 90km outside Paris. Mancoba gained his French citizenship in 1961.

Sculptors and painters

Knock says in an interview (in French) with essayist and literary critic Eryck de Rubercy (2019) in Revue des Deux Mondes that Mancoba was first a sculptor and Ferlov initially a painter. Their work influenced each other’s and should be seen together. Mancoba later went towards painting and drawing and Ferlov went towards sculpture.

Sarah Ligner, curator at Musee du Quai Branly in Paris, who completed her master’s thesis on Mancoba in 2005, reiterates this lifelong conversation between the two artists in the same interview: “Parallels can be drawn between the couple’s works. Sonja Ferlov Mancoba and Ernest Mancoba share the same philosophical and political aspirations. This unity generates correspondences in their aesthetic research … Despite this difference of medium, their creations register very early on a tension between figuration and abstraction. Distinct in their formal vocabulary, their works resonate in their expression.”

Huge influence

“The show is built as a dance,” added Knock when she initially walked with me through the exhibition, which also plays off the title I Shall Dance in a Different Society. We see this too in the dialogue between the work of Mancoba and Ferlov, conversing across separate exhibition spaces, as well as in the interventions by contemporary artists in engaging with Mancoba’s work, acknowledging his legacy and influence in their contemporary practice.

“It aims at making space for a spiritual experiment … oscillating between the material and the immaterial, figuration and abstraction. The diversity of his practice, from sculpture to drawing, from line to colour, as well as the shamanic continuity,” adds Knock.

As part of these conversations with contemporary artists, a series of related performances took place on September 4 in the intermediate space between the two exhibitions. Organised in partnership with AFRIKADAA — a Franco-Senegalese association that aims to promote and develop art and artists from or related to the African continent and its diasporas — these distinct visual and musical performances by Myriam Mihindou, Fabiana Ex-Souza, Chris Cyrille and Yann Cléry paid tribute to Mancoba’s influence on modern and contemporary African art. The performances symbolically and magically brought the two exhibitions together, evoking the spirits of Mancoba and Ferlov and bringing the artist couple together once more. Artist Euridice Zaituna Kala did a separate performance on September 16.

Included in the Mancoba exhibition in different media were artworks by contemporary artists Wa Lehulere, Mo Laudi, Kitso Lynn Lelliott, Mihindou and Chloé Quenum.

“I worked only with people who understood from the inside. We’re here in this national museum of modern art. Ernest is a source for artists and people. We belong to this heritage,” Mihindou told me.

“There is a sense of history around Mancoba. There is another kind of tradition that emerges out of it,” explained Knock.

When Mancoba left Cape Town in 1938 “he was already a BA graduate from Unisa and a recognised sculptor, although he had received no formal training in art”, according to South African art historian Elza Miles in her book Lifeline Out of Africa: The Art of Ernest Mancoba (1994, Human and Rousseau).

Mancoba had a natural talent for sculpture, as can be seen in his earliest public commission for the Grace Dieu chapel when he was only 25 years old. Entitled Bantu Madonna (1929), it is noted as the earliest South African example where the Virgin Mary is portrayed as black. “Edith Ntomtela recalls how one of the schoolgirls posed for the carving and Mancoba himself remembers arranging the folds of her drapery,” Miles wrote.

Black Virgin: Ernest Mancoba was 25 when he sculpted Bantu Madonna. (Johannesburg Art Gallery, Norval Foundation © Courtesy of the Estate of Ferlov Mancoba)

Mancoba intended the viewer “to feel under the surface of the classical mould an African heartbeat,” he told prominent Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in a celebrated interview first published in Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art (2003). Carved in indigenous South African yellowwood, the sculpture was one of about 50 original artworks by Mancoba on display at the exhibition.

Although fellow artists Irma Stern and Lippy Lipshitz praised him for his carvings, he later reflected to Miles in letters that he started to pay less attention to his sculpture even before his departure, because Africans were taught under colonialism “that it is the intellectual gifts that make men great and not the work of their hands”.

An artist abroad

Mancoba was the first black South African artist we know of to study in Paris. Other household names in early South African modern art who went abroad studied in the Netherlands (in the case of Pierneef who in 1901 was at the Rotterdamse Kunstakademie), in Germany (in 1913 Stern enrolled at the Weimar Academy), or England (in the case of Maggie Laubser, who in 1914 was at the Slade School of Art in London).

It was Mancoba too who encouraged Gerard Sekoto (1913–1993) to quit South Africa and join him in Paris, which Sekoto eventually did in 1947. The two artists taught at Khaiso Secondary School in Pietersburg in 1937. Both trained at Grace Dieu, the Diocesan teacher’s training college in Pietersburg, albeit at different times, because Sekoto was nine years younger.

Mancoba was not the first African artist to study in the French capital though. For example, Nigerian artist Aina Onabulu studied at the Académie Julian, a private art school in Paris, before moving back to Nigeria in 1922.

Mancoba’s story and his oeuvre are links between African aesthetic traditions and Paris’s early 20th century modern avant-garde movements. It helps us reimagine the place of African artists in modern Western art history.

Ligner said that for Mancoba the choice to leave South Africa for Paris “was so that he could be in dialogue with artists sensitive to the aesthetic qualities of African art, like Maurice Vlaminck, André Derain, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso … they [he and Ferlov] met Joan Miró, but also Alberto Giacometti and Henri Geotz, who were their neighbours …”

It was the dream of many artists to go to Paris at this time. Facing racial discrimination at home, it must have conjured up for Mancoba the idea of a utopia free from bigotry, and of a society that supported its artists.

Simon Njami writes of 1920s Paris in Revue Noire (Paris — The lost illusions, 1996): “The myth of France as a land of political asylum and of intellectual enlightenment is still alive [at this time] … the myth of the French Revolution of 1789 and the myth of a country without prejudice … ”

Others say this was not the reality that greeted them upon their arrival in Paris, and Mancoba’s story reflects this. In turn the Parisian image of African art in the late 1930s was filled with ideas of traditional masks and figurines, not of African avant-garde painters.

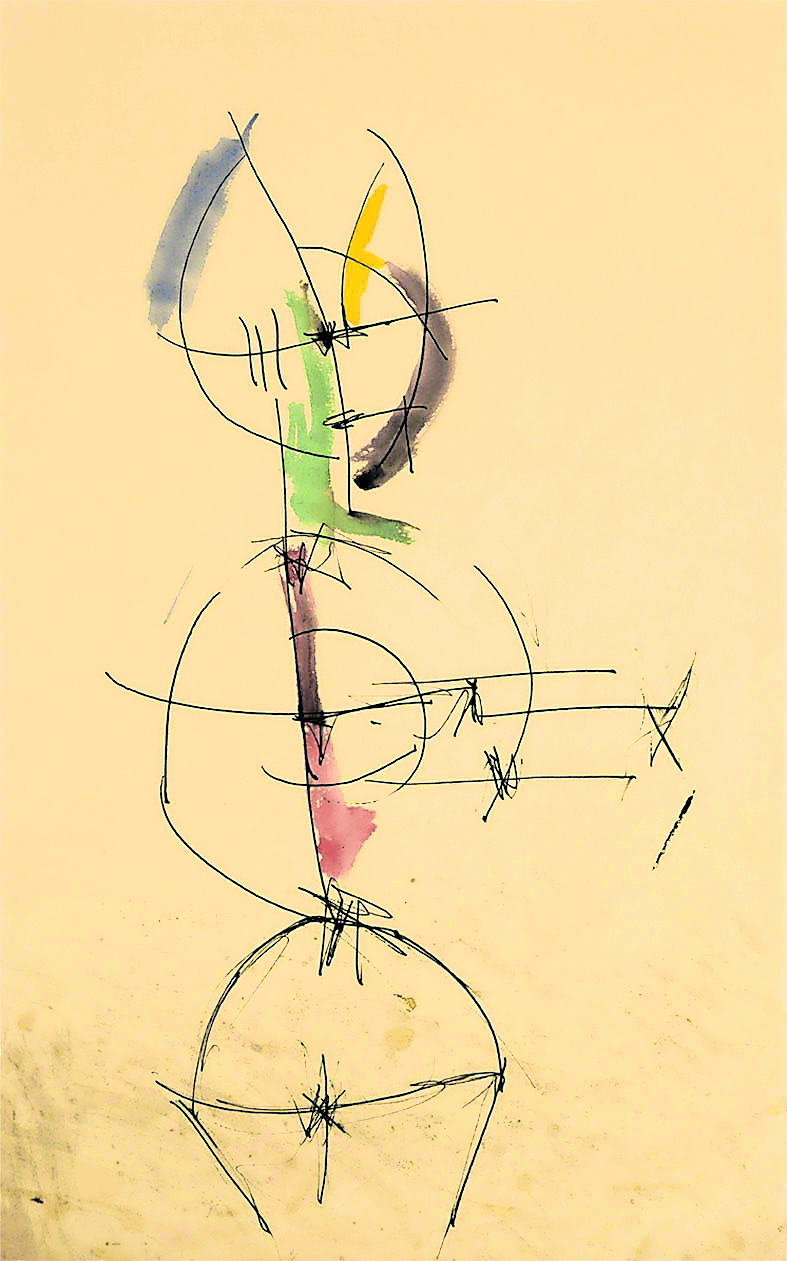

Untitled. (A4 Foundation, Cape Town, Collection Mikael Andersen © Courtesy of the Estate of Ferlov Mancoba)

Mancoba was likely seen through this prism of traditional African art, though he studied at the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs in Rue d’Ulm, an art school in Paris that produced renowned artists such as Matisse.

“Some critics totally obliterate my participation in the [CoBrA] movement, as modest as it admittedly has been, in the reason that my work was suspected of not being European enough, and … [of] ‘betraying (my) African origins’,” he told Obrist.

‘Inert’ African art

Mancoba, along with other African artists, was still struggling to be recognised as modern and contemporary in the middle of the 20th century. That African art is in a state of flux and constantly evolving was not widely known at this time and not even much later, at the end of the century.

The chief editor of Revue Noire, Jean Loup Pivin, writes critically on this issue in his 1996 article (“The dusk of idols): “We cannot go on much longer being satisfied with a recognition of ritual African arts that are still stubbornly called primitive without the new, modern Africa being able to express itself. So that being African doesn’t transform you into a terrifying living mask for the white Parisians …”

These essentialist and outmoded notions of African art as perpetually static and inert, which Pivin refers to, are connected to long-standing and clichéd European ideas of Africa and Africans.

Ligner makes an acute observation in an article she penned in 2015 (“Ernest Mancoba: A modern African artist?”) that Mancoba’s work was not included in the celebrated Magiciens de la Terre exhibition held the Pompidou and the Grande halle de la Villette in Paris in 1989.

This exhibition of contemporary art featured the work of an equal number of Western and non-Western artists, with the likes of heavyweight Western artists of the time such as Marina Abramovi (Serbia), Christian Boltanski (France), Anselm Kiefer (Germany), Barbara Kruger (United States), Richard Long (United Kingdom), Claes Oldenburg (Sweden) alongside Nam June Paik (South Korea) Esther Mahlangu (South Africa), Kane Kwei (Ghana), Twins Seven Seven (Nigeria) and Chéri Samba (Democratic Republic of the Congo) representing some of the artists from Africa and the rest of the world.

Some of the criticism directed at Jean-Hubert Martin, curator of the exhibition, was that the African artists selected were generally self-taught artists or artists working in traditional ways and not reflective of contemporary art from the continent and the African diaspora.

Mancoba’s Painting (1965) had already been acquired by the French National collections in 1976, and two lithographs were added to the collection later in 1989. In 2013, the Centre national des arts plastiques deposited the same Painting at the National Museum of Modern Art (Pompidou), De Rubercy informs us.

“The museum is the only museum to have a painting by Ernest, acquired under Pontus Hulten, the Swedish director of the Pompidou at the time. He was familiar with the CoBrA group,” Knock told me.

So, it was not that Mancoba was not known in Paris at the time of Magiciens de la Terre, rather that “he was not European enough” and, after studying in Paris and living in Europe after all this time, was perhaps not considered African enough, for the likes of the curators of the show.

Late acknowledgement

This is why the retrospective in the revered space like the Pompidou, initiated and fund raised by Knock, a curator at the institution, is such a crucial intervention. Even more so that it was timed to coincide with the retrospective on Ferlov. It is the first proper acknowledgement in France of Mancoba’s legacy, one also inextricably linked to Paris and to that pioneering generation of African artists, until now, unacknowledged in the modern Western art narrative.

Knock did a exceptional job in creating an exhibition that was well researched, rich and complex. The exhibition had several layers to it and was divided into three main areas: archives, studio work and a “memory chamber”.

The first room of archives served as an introduction to Mancoba’s life: his arrival in Paris, where he studied, the artists and people he engaged with, the places he lived, his thoughts and writings quoted on the wall, personal photos from the different periods of his life, private letters and correspondences, passports, newspaper cut-outs featuring the artist, books that he read, and personal objects. All this while the artist’s voice, lifted from interviews, constantly hummed in the background, filling the room with his presence.

It seemed important to Knock to acknowledge the artist’s spiritual aura, as she pointed out to me on several occasions. As Mancoba himself told Obrist, “ … I only paint or carve when a spirit calls on me … ”

A printed image of the shopfront that had become the artist’s home in central Paris from 1961, with Ferlov and Wonga, initially adorned one wall. Kitso Lynn Lelliott was invited to create a video installation, produced while in residency at the Cité internationale des arts, which was projected on the same wall in the last few weeks of the exhibition. In it she ghosted her own figure moving in front of an image of the same façade, via video overlays, bringing to life the otherwise static image behind her.

This double layer of the shop frontage, a fixed printed image under which Lelliott’s projection of her active image on a white sheet loosely hanging, created an agreeable tension. The thin fabric also evoked the only material that separated Mancoba and Ferlov’s workspaces in their 40m studio home in the Montparnasse district.

The walls in this preliminary room served as a timeline, marking important moments in Mancoba’s life and career. Importantly, it also marked disappointments, such as the CoBrA shows he was not included in, indicated via strike-through vinyl texts.

Ferlov and Mancoba were invited by director William Zandberg to exhibit with the group at the Stedelijk Museum in 1949, but Mancoba never took part that exhibition because of a fallout in the group.

“He was the only black person in the CoBrA group. The black dot of the group. The invisible man. He was seen as Sonja’s partner, someone accompanying her [in Denmark], because of the racism of the time,” said Knock.

Mancoba told Obrist: “The embarrassment that my presence caused — to the point of making me, in their eyes, some sort of ‘invisible man’ or merely the comfort of a European woman artist — was understandable, as before me, there had never been, to my knowledge, any black man taking part in the visual arts ‘avant-garde’ of the Western world.”

In Mancoba’s own words we hear that he was a pioneer African artist in being a part of CoBrA, a major avant-garde Western art movement (Cuban Wilfredo Lam was part of the Surrealist movement in Paris).

Mancoba was eventually appropriately acknowledged in Denmark with retrospective exhibitions dedicated to his work at the Aarhus Kunstmuseum and the Holstebro Kunstmuseum in 1969 and at the Københavns Kunstforening in Copenhagen, the Fyns Stifts Kunstmuseum in Odense and the Silkeborg Kunstmuseum in 1977, finally marking his contribution to the Danish contemporary art scene.

Recognised at home in 1994

Back in South Africa, Mancoba was recognised in the historic year of its first democratic elections. Elza Miles curated the exhibition Hand in Hand on the work of Mancoba and Ferlov at the Johannesburg Art Gallery (1994) and at the South African National Gallery (1995). Miles had first encountered Mancoba’s work included the in 1983 in the CoBrA group retrospective exhibition held at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1983.

In 1994 Brigitte Thompson made Ernest Mancoba at Home, a short documentary film about the artist, and in 2006 curated an exhibition on Mancoba’s work, with an accompanying catalogue headlined “In the name of all humanity: The African spiritual expression of E Mancoba, at the Gold of Africa Museum in Cape Town”.

As one moved into the next room, which opened to reveal Mancoba’s studio practice and which occupied the main space in the exhibition, one passed through two interventions by contemporary artists that reflect on the artist’s work.

The one was a 2019 sound piece, Motho ke Motho ka Batho (A Tribute to Mancoba), by Paris-based Afro-electro DJ Mo Laudi, intimately listened to with headphones, which used Mancoba’s voice mixed with Laudi’s original ambient compositions in the background, along with other archival South African sounds such as Marikana miners chanting a year after the massacre, and music samples from Solomon Linda’s Mbube (1939), among others.

The second was a 22-minute video piece by Wa Lehulere, Where, If Not Far Away, is My Place? (2015), which was made from video footage of the critical Obrist interview with Mancoba. Through it Wa Lehulere directly confronts the audience with the artist’s moving image and voice, restoring his memory into art history, together with Obrist, while peppering the video with rolling text edits, silences, and animated white chalk line drawings on blackboard.

Wa Lehulere’s punctuations slowly merge into the impression of the central figure image, so dominant in Mancoba’s drawings and paintings from his later decades, which was inspired by the Bakota funeral effigies of Gabon that he is said to have encountered at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris.

Knock included a second artwork by Wa Lehulere, Does This Mirror Have a Memory? (Ernest Mancoba) 1986-2015, in the “memory chamber”, the third and final area of the exhibition. This was a powerful and evocative wood carving, with small details such as a piece of cloth and a feather on top, recalling the influence of Bakota figures. It echoed the sharp, incisive lines of Mancoba’s first linocuts such as Untitled (1962), on exhibition in the same area.

Wa Lehulere’s contemporary wooden statuette was deliberately positioned in conversation with Untitled, (1986), a lithograph by Mancoba, in which the central funerary figure can be clearly seen in hard-edge black lines on off-white paper. It is an interesting triangle, with Mancoba being inspired by the Bakota figures and Wa Lehulere drawing inspiration from Mancoba and interpreting the funerary figures in praise of the elder artist.

“Wa Lehulere’s film was acquired for the Pompidou collection and this sparked the idea for the Mancoba exhibition. It started with Kemang; he drew my attention to Ernest Mancoba,” Knock told me.

Influences

Some of the elder artist’s early ink drawings such as Tegning from 1939 explicitly reveal the inspiration he drew from African masks, which Miles attributes to the mboom initiation masks from the Congo, which he is said to have encountered at the British Museum in 1938, then the Museum of Mankind, before making his way to Paris.

Miles noted that Mancoba created his first oil painting in 1940, while interned, in the war camp at St Denis, just outside Paris. He turned more and more to painting and drawing after the war.

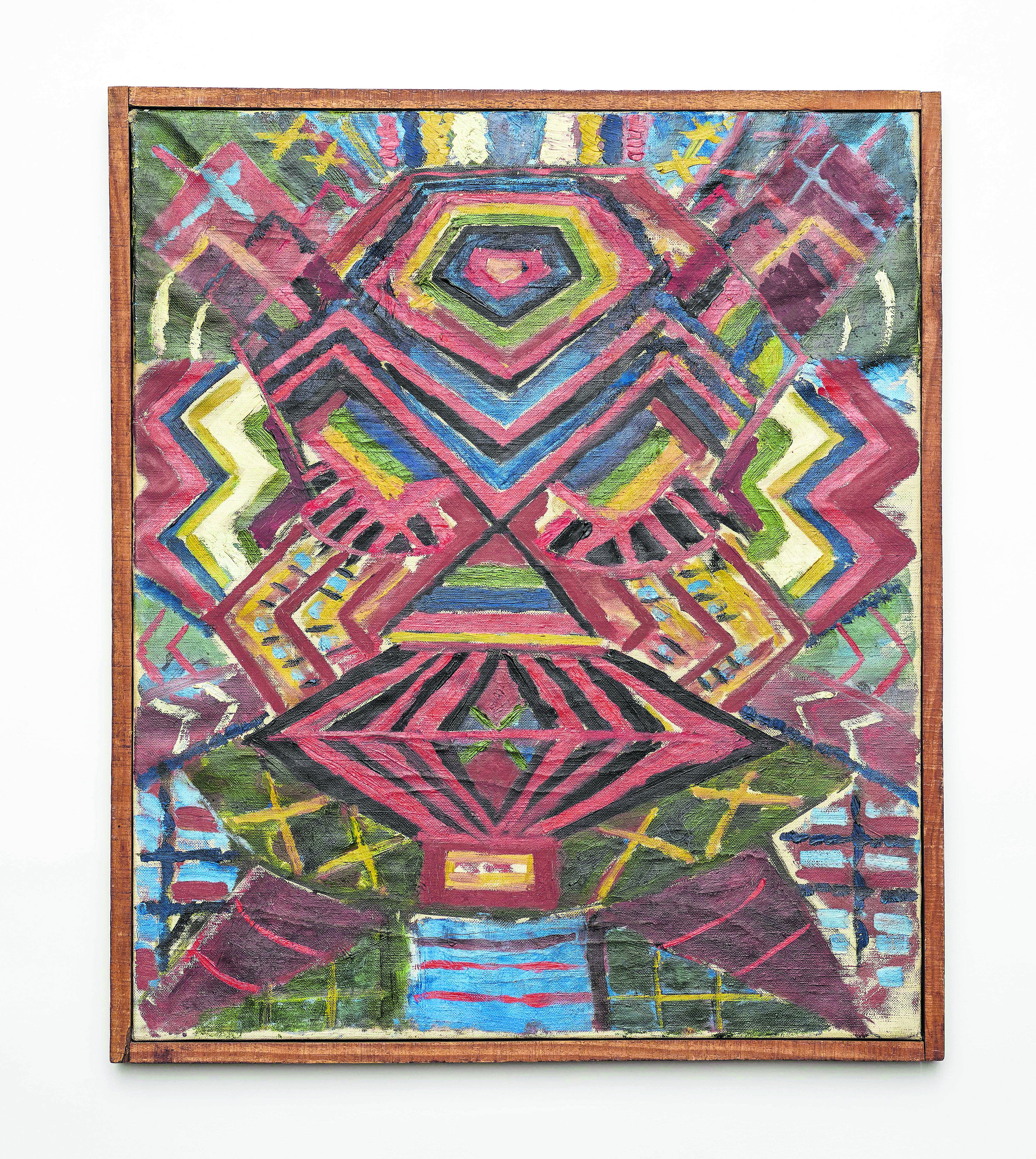

His colourful oil on canvas Composition (1940), an abstract work in strong contrasting geometric lines of colour, dominated by reds, greens and ochres with darker areas in blue, make explicit reference to masks. Emerging in this work is the artist’s ambiguous dance between abstraction and figuration, and the figurative in his abstraction.

Composition is A4 Foundation, Cape Town, Collection Mikael Andersen © Courtesy of the Estate of Ferlov Mancoba

Painting (1951) was one of my favourites of the exhibition, with broad, bold shapes in ochres, greys and browns dominating the mood, highlighted by a few shapes coloured in blue and green, and fewer still (two each) in red and white. A thin blue outline defines the almost rectangular shapes. It is less clear in this painting to identify either a mask or a funerary figure, and appears to be an abstract work completely liberated from figuration.

Untitled (1959) with brighter shades of the same palette is an equally, if not more beautiful work, with lighter and more painterly brush strokes. We start to see hints of the naked canvas beneath. The mood is light and even jovial.

Mancoba often worked on both sides of the canvas, giving testimony to the couple’s “difficult material conditions.” Although this scarcity has been well documented, the artist emphasised that his hope was always to convey his vision as discretely as he could, “with the least material means possible”.

Knock was attentive to this detail, and at least two transparent glass windows cut into the exhibition walls reveal the flipside of these works, one of which is L’Ancêtre (1968-1970). In these later paintings the canvas is sparsely painted; the brush strokes are looser and freer, painted on with a deftness of touch, with a brighter halo effect around the lightly-gestured funerary shape figure.

Two small but important curatorial interventions were gems in the exhibition, both displayed on tiny monitors. The one was film footage shot by Dada and Surrealist artist Ray from Danish collector Karl Kjersmeier’s collection of African art. “Sonja grew up with a very important African collection, [that belonged to] friends of her parents. One of the biggest collectors of African art in Europe,” Knock told me, referring to Kjersmeier’s collection. The other monitor displayed intimate footage of the three members of the Mancoba family walking together on a beach somewhere, far away from the camera.

The exhibition also showcased Mancoba’s ink drawings on paper dating from the 1960s, influenced by Inuit objects he had seen in Copenhagen. Knock’s inclusion of Chloé Quenum’s tiny jade carvings in this exhibition, inspired by historic Oceanic and West African art, evoke Mancoba’s interest in the spiritual, deeply symbolic and coded means of expression. The artist’s ink and watercolour drawings were some of the most powerful works in the exhibition. Untitled (undated) minimally echoes the essential lines of shapes suggested in his paintings, although with the most subtle subtlest gestures in colour and form that are both gestural and simultaneously thoughtful.

The artist’s oeuvre is completed with his calligraphic drawings, a system of coded signs created in the 1990s, after the death of his wife in 1984. This secret language system recalls Ivorian artist Frédéric Bruly Bouabré (1923-2014), who developed his own drawn language system in signs and images, annotated in postcard-size colour drawings. Bouabré was included in Magiciens de la Terre.

Once in a lifetime

It was a rare treat to experience an exhibition dedicated to the South African experimental and pioneering avant-garde artist at the Pompidou. A once in a lifetime occasion perhaps. There was talk of the exhibition touring to the US and South Africa. I do hope so. This exhibition needs to be seen everywhere, but it is especially important to be seen in South Africa and in other countries in Africa.

Knock is working on a book on Mancoba, which will be out sometime next year.