(John McCann/M&G)

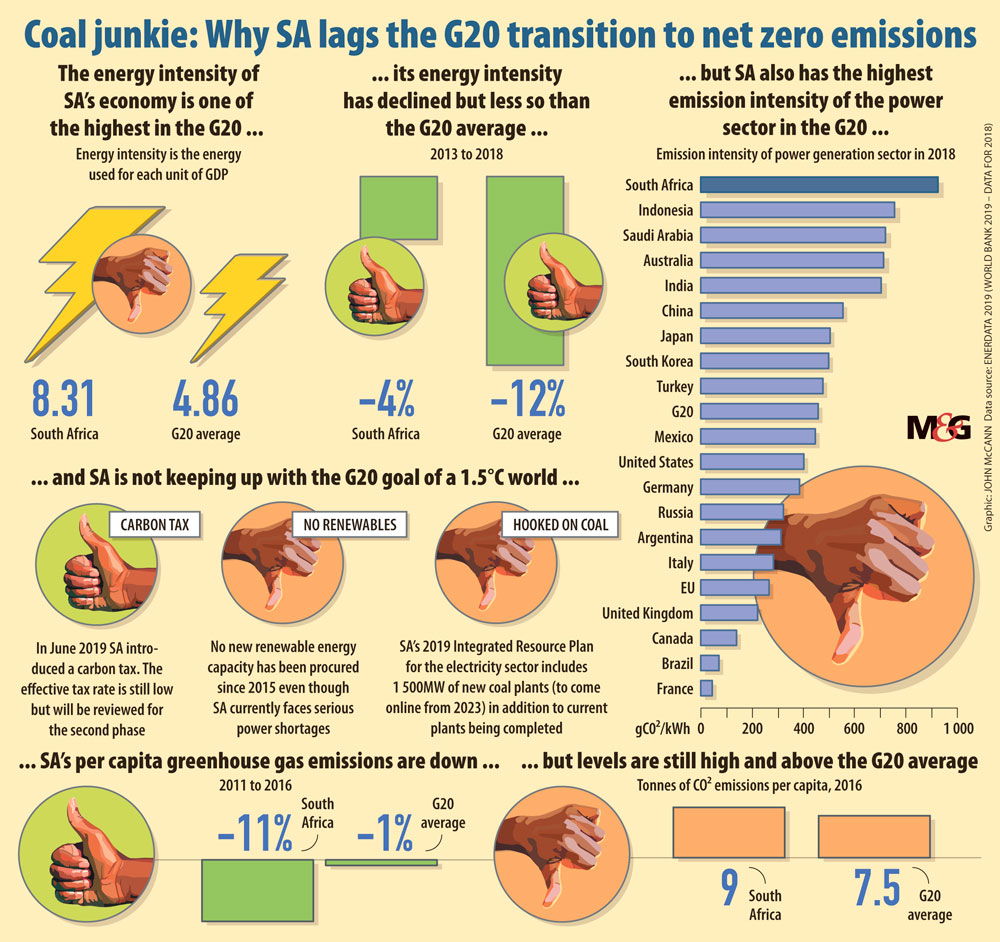

A report, Brown to Green: G20 Transition to a Net-zero Emissions Economy, published on Monday by a global nongovernmental organisation coalition, Climate Transparency, says South Africa’s per capita greenhouse gas emissions are above the G20 average and that we are the most emissions-intensive of all G20 countries.

The report says to meet commitments South Africa has made to meeting emissions targets, the country needs to stop building new coal plants, including finishing the two units at Kusile, establish timelines to phase out existing coal-fired power stations and accelerate the decommissioning of plants too costly to retrofit to meet air-quality standards.

“South Africa’s emissions increased by 41% between 1990 and 2016, mainly driven by emissions from energy. Under current policies, it is possible that South Africa will meet the upper end of its NDC [nationally determined contributions] range in 2025 but not achieve its 2030 NDC target.

“South Africa will need to scale up climate action to meet the lower-end of its NDC in 2025 and 2030, with even more effort required to become 1.5°C compatible,” says the Climate Transparency report.

The report notes that almost 23 000 people die in South Africa every year as a result of outdoor air pollution: because of strokes, heart disease, lung cancer and chronic respiratory diseases.

South Africa, together with two other outliers, Turkey and Indonesia, “urgently need to develop coal phase-out plans and stop building more coal power plants”, Climate Transparency says, noting that “no new renewable energy capacity has been procured since 2015, despite the country facing acute power shortages at the moment”.

Argentina, Indonesia, South Africa, Italy, Turkey, Australia, the United Kingdom and Russia provide the highest fossil fuel subsidies per unit of gross domestic product in the G20. “In Argentina, Indonesia, South Africa, Italy and Turkey, the vast majority of subsidies are for fossil fuel consumption, and mainly constitute fuel and energy tax breaks to different sectors,” the report says.

In South Africa’s case the Brown to Green report quantifies the value of fossil subsides at $2.3-billion annually, mainly in the form of an exemption from paying VAT on fuel sales.

It says South Africa’s 2019 Integrated Resource Plan for the country‘s electricity sector includes 1 500 megawatts of new coal plants, to come online from 2023 onwards, in addition to the current plants being built. “South Africa’s reliance on coal is high (70% of the energy mix) and expected to increase with current plans,” the report notes.

Fossil fuels still make up about 88% of South Africa’s energy mix, including power, heat and transport fuels) — among the highest in the G20 — while energy supply from renewables has barely increased over the past two decades. The report says the share of fossil fuels globally needs to fall to 67% of global total primary energy by 2030 and to 33% by 2050.

South Africa has the highest share of coal power in the G20, yet has no plans to effectively phase it. Private sector investment in renewable energy has, however, established a sizeable footprint, contributing 5% of total generation.

“Coal must be phased out in the EU/OECD [European Union/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries] no later than 2030; in the rest of the world no later than 2040. Electricity generation needs to be decarbonised before 2050, with renewable energy the most promising option,” Climate Transparency says.

Total greenhouse gas emissions by South Africa have increased 39% since 1990, but in recent years have been almost constant, owing largely to low economic growth and declining electricity intensity. In June this year, South Africa introduced a carbon tax. The effective tax rate is still low, but it will be reviewed for the second phase, according to the Brown to Green report.

“The [Integrated Resource Plan] 2019 also proposes an expansion of renewable energy capacity from 3 800 MW (excluding large hydro) to a total of 26 700 MW (plus a projected 6 000 MW in distributed PV [photovoltaic]) in 2030. However, no new renewable energy has been procured since 2015, and there is no 2050 renewables target,” the report notes.

In addition to Indonesia, Turkey, and South Africa, a coal phase-out plan is also needed in Australia, India, Japan, Mexico, Russia, South Korea and the United States.

Economic shifts and policy changes may turn fossil fuel infrastructure into stranded assets, the B2G report warns. “For example, in India 40GW of coal-fired power capacity that has been commissioned or is under construction is already ‘stressed’. If China implements its NDC, there could be stranded assets of $90-billion from coal power plants by 2030.”

Relying on imported fossil fuels can cause economic vulnerability through making countries and businesses subject to volatile fuel prices, switching to renewably sourced energy inputs such as from sun and wind, can mean increased energy independence and maximised fiscal benefits such as improved balance of payments.

The B2G report estimates that economic growth from climate-friendly technologies could trigger $26-trillion in investments and generate 65-million more jobs worldwide by 2030.

“Low-carbon alternatives are becoming cheaper. By 2025, electricity generation from new renewable energy infrastructure will be cheaper than from new coal infrastructure. As batteries drop in price, electric vehicles will by 2024 become cheaper than their counterparts with combustion-engines.”

The B2G report says “coal is a major – and often the leading – contributor to air pollution. Coal burning is responsible for more than 800 000 premature deaths a year globally and many millions of cases of serious and minor illness. This also has economic implications, such as increased healthcare costs and a higher number of lost working days.

The Climate Transparency report says that Brazil, China, the EU and Germany have policies to reduce coal, but should plan for a 1.5°C compatible phase-out (in Germany, the 2038 end date for coal is not 1.5°C compatible). Australia, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey and the US need to urgently start with substantial policies to reduce coal use and ensure no further investments in new coal capacities, while at the same time developing a phase-out plan.

“G20 countries need to have 100% zero-carbon electricity in 2050, ideally through renewables that have fewer environmental and human rights issues than nuclear and hydro. To reach this target, Argentina, China, the EU, France, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey and the UK have to develop long-term strategies to build up and improve their national incentive schemes,” says the report.

Climate Transparency says that several G20 countries need to address the social consequences of a transition in the power sector. A coal phase-out can have implications for workers, communities, enterprises and lower-income households, depending on the importance of coal for the national and regional economies.

“Several measures could ensure a just transition for the workforce, such as retraining or the development of new green jobs. In 2019, Canada, Germany and South Africa made progress on the development of just-transition plans for coal workers and regions,” the report notes.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)