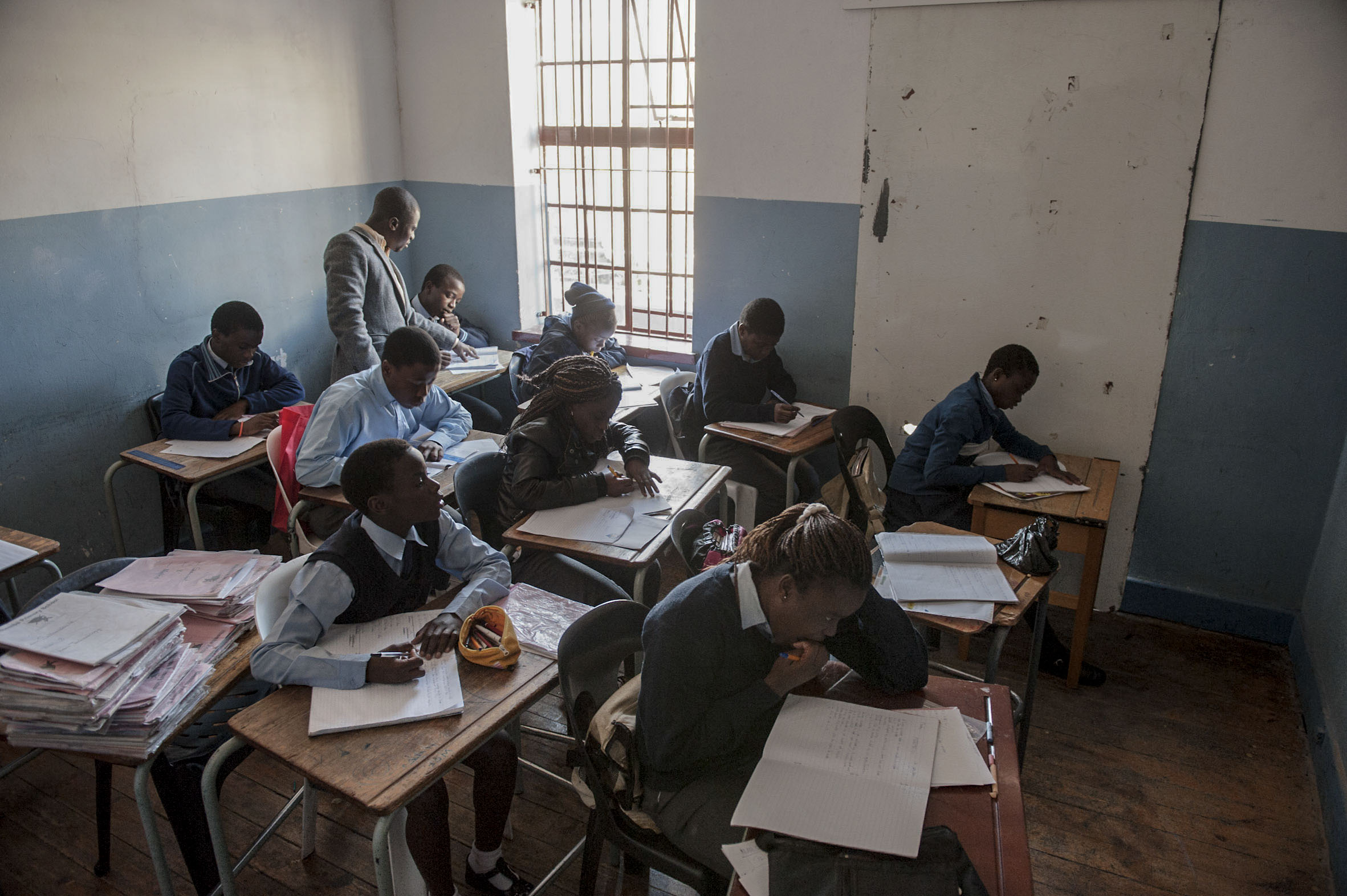

Struggle: With help from the UN Refugee Agency, Gift a South Sudanese refugee, attends school in Biringi settlement in the DRC. (John Wessels/UNHCR)

A report on displaced people criticises governments that fail to ensure the children get a good education — but recognises that the top refugee hosting countries have made progress in including them in national education systems. It also assesses the effect of seasonal migration and the climate crisis on schooling. Bongekile Macupe digs into the report

‘Education is a human right and a transformational force for poverty eradication, sustainability and peace. People on the move, whether for work or education, and whether voluntarily or forced, do not leave their right to education behind.”

So wrote United Nations secretary general António Guterres in Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls, the 2019 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) report published last month by the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco). The report assesses annually progress towards achieving sustainable development goal 4 on education.

This year the GEM report looks at how countries handle migration and displaced people and how that affects the education of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants.

In the foreword, Unesco’s director general, Audrey Azoulay, says laws and policies are failing migrant and refugee children by negating their rights and ignoring their needs, and yet these are some of the most vulnerable people in the world. They are also being denied entry into schools that are supposed to be safe havens for them.

“Ignoring the education of migrants squanders a great deal of human potential. Sometimes simple paperwork, lack of data or bureaucratic and unco-ordinated systems mean many people fall through administrative cracks,” she says.

“Yet investing in the education of the highly talented and driven migrants and refugees can boost development and economic growth not only in the host countries but also countries of origin.”

The report estimates that as of 2017 there were 87.3-million displaced people in the world — the highest number since the end of World War II. Of these people, 25.4-million are refugees, 3.1-million are asylum seekers, 40-million have been displaced by conflict and 18.8-million were forced to move, albeit for shorter durations, because of natural disasters.

More than half of all refugees are under the age of 18, and that at least four million aged five to 17 did not attend school in 2017.

Although the report says little about South Africa and how it fares compared with other nations, Anjuli Maistry, an attorney at the Centre for Child Law, says this should not be interpreted as there being no similar problems in the country.

A teacher who fled Zimbabwe in 2005 started a school for refugee children in her suburb, Yeoville, in Johannesburg. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

A teacher who fled Zimbabwe in 2005 started a school for refugee children in her suburb, Yeoville, in Johannesburg. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

In her work, Maistry’s focus is on refugees, migrants, asylum seekers, migrants who are not documented (classified as illegal foreigners) and South African children who do not have documents.

She says refugee and asylum seeker children are often removed from school or not admitted at all because they cannot produce a study permit, even though they may have asylum or refugee papers. The national admission policy says that learners need to produce a study permit or produce proof that they have applied to legalise their stay. If they cannot, they should be removed from the school.

Maistry says that denying children the right to an education because they do not have a study permit shows that principals have incorrectly interpreted the admission policy.

“We should be doing away with documentation to access such a basic right as education. There are thousands of children, even South African, who cannot get documents. It is an irreversible damage in a child’s life if they don’t get to go to school.”

The Centre for Child Law is awaiting a judgment by the high court in Makhanda (formerly Grahamstown) after it took the departments of basic education and home affairs to court to get undocumented learners to be allowed to attend school.

Schools must prepare for climate change

The unfolding climate crisis could be the leading cause of displacement in the coming years and this could place education systems at risk, predicts the Global Education Monitoring report, published by Unesco.

This is in terms not only of loss of life but also through infrastructure damage.

The report, Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls, has suggested that governments, if they have not already started, should make the necessary plans to minimise the risk.

“Within a few decades, climate could be a main reason for displacement. ‘Environmental refugee’ or ‘climate refugee’ defines any individuals leaving their homes because of climate change effects, such as sea level rise, drought or desertification, although the terms do not yet carry legal implications,” it states.

The report adds that governments’ capacity should be strengthened so that education services are disrupted as little as possible during natural disasters.

The report looks at nation states in the Pacific Ocean, which are increasingly planning their education around the reality of natural disasters. In the Solomon Islands, the government has plans that enable people to continue studying before, during and after a disaster.

The Solomon Island recommend that “all teachers in affected areas should be trained in psychosocial strategies within two months of the disaster, and psychosocial activities should be introduced in all temporary learning spaces and schools within six weeks”.

In the Kiribati island country (it has 33 islands, 20 of which are inhabited), the government has a relocation strategy for anyone who wants to leave the state. This includes raising people’s qualifications so that they can get decent work abroad in countries with ageing populations, such as Australia, Japan and New Zealand, where there will be a shortage of skilled workers.

Closer to home, long-term climate scenarios have shown that droughts and crop failures will probably result in more migration in Southern Africa. This will force countries to take people in, and they will then need to have systems in place to ensure children get an education

Seasonal migration affects education

Millions of children whose parents are seasonal labour migrants are either deprived of an education or it is disrupted — and they too may have to work.

According to the Global Education Monitoring report, Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls, published by Unesco, children “are often treated as an additional workforce and may have to leave school to work”.

The children of migrant workers on farms in South Africa have also been affected.

“A lack of accessible, affordable day care in rural areas meant younger children were brought to the fields and exposed to the same workplace hazards as their older siblings and parents,” the report states.

The report gives staggering numbers that show how seasonal migration has had a negative effect on the education of children around the world.

A 2010 study in Turkey looking at children aged six to 14 who participated in seasonal agricultural migration found that although 97% were attending school, 73% started school at a late age, and they were absent for an average of 59 school days out of 180.

In India, 10.7-million children aged six to 14 lived in rural households with a seasonal migrant in 2013. About 28% of 15- to 19-year-olds in these households were illiterate or had not completed primary school, compared with the cohort overall. It was also found that there were no education facilities near work sites for about 80% of seasonal migrant children in seven Indian cities — and 40% of them worked, experiencing abuse and exploitation.

A survey in 2015-2016 in Punjab in the northwestern part of India found that between 65% and 80% of children aged five to 14 worked in the construction sector for seven to nine hours a day.

Some countries are trying to remedy the effect of seasonal migration on children’s education. In Thailand, for example, partnerships between civil society organisations and the companies employing seasonal labour migrants have established partnerships. The solutions include the provision of mobile schools, and teams of teachers, that then rotate through the areas where migrant labourers spend their time.